You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The future of government housing investment - bricks or benefits?

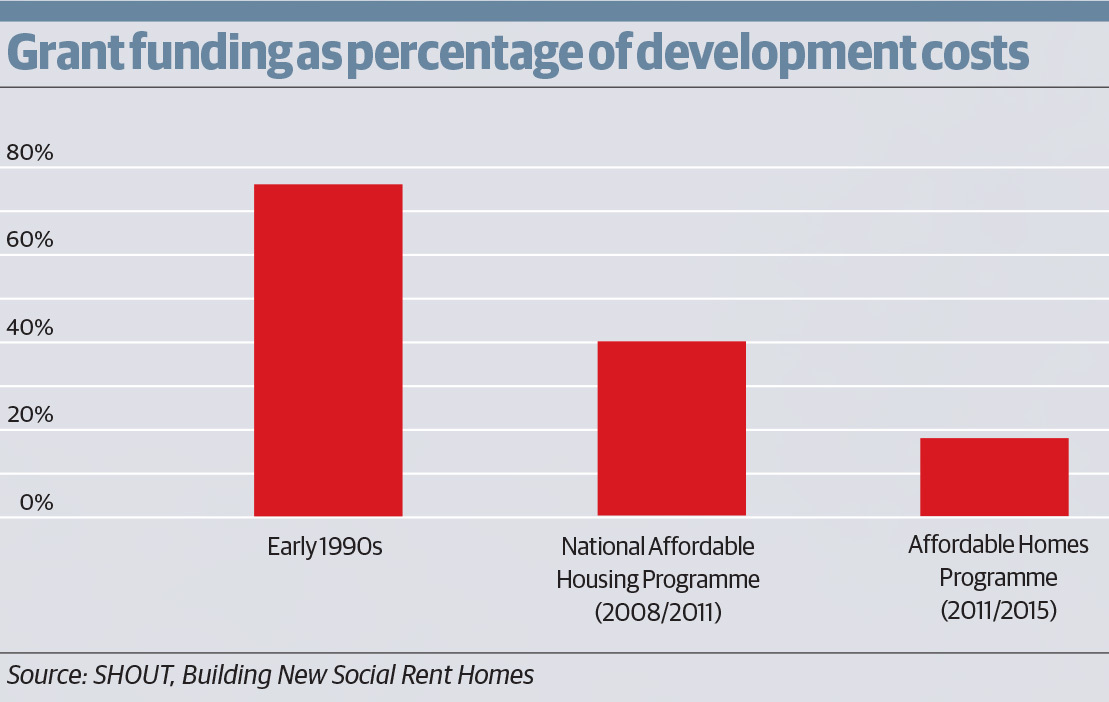

Successive governments have invested in housing benefit rather than directly in new homes. A new report out this week makes a compelling economic case for capital investment in social housing. Sarah Graham finds out more.

Source: Paul Young

The funding of social housing has long been the subject of ongoing debate across the sector and political sphere. On the one hand, there’s rent subsidy in the form of housing benefit – the line most heavily pursued by the current government; on the other, there’s capital investment in new social housing, which successive governments have been more resistant to funding.

Yet SHOUT is hopeful that its latest report, published this week, ‘conclusively and irrefutably proves that the case for social housing is unanswerable’.

So is it case closed?

Financial implications

The analysis, carried out by macro-economic research consultancy Capital Economics, is certainly compelling. Commissioned by SHOUT and the National Federation of ALMOs (NFA), Building New Social Rent Homes sees the global financial research firm investigate the financial implications of a proposal to invest in 100,000 new social homes each year.

Using exemplar households, the report compares SHOUT’s capital investment proposal to the current government policy, where the focus is on subsidising rents through housing benefit.

In what SHOUT is hailing as an important tool for the social housing sector, Capital Economics’ report states: ‘From our analysis, we have a stark and clear finding: the government would achieve better value for taxpayers’ money, as well as improve the living standards of many low-income households, if it were to part fund the delivery of 100,000 new social rent homes each year rather than continue with its existing policy.’

Under the government’s current housing strategy, Capital Economics states that ‘little housing is being built at traditional social rents, and only very modest levels of build for so-called “affordable rent” is taking place’, which they describe as unsustainable.

Further, noting that the current allocation of public expenditure on housing does not take into account the future welfare costs of subsidising higher rents in the private and ‘affordable’ social rented sectors, the report condemns the government’s existing housing policy as ‘a form of fiscal myopia: saving pennies in the short-term only to waste pounds in the future.’

This is where capital investment comes in. According to the report, the under-supply of social housing means an increasing number of low-income households are housed at higher ‘affordable rents’ in the social sector, or even higher rents in the private rented sector, contributing to a housing benefit bill of £24.3bn.

Claimants living in privately rented accommodation received on average £110 per week in November 2014, compared to £89 for social rent tenants – a difference of £21 per week, which the report uses to illustrate how an increased supply of social housing would help to reduce the government’s welfare bill. The report also forecasts housing benefit soaring to almost £200bn by 2065/66 if current trends continue, with private rented accommodation accounting for 63% of that total, compared to 37% today.

Besides welfare savings, Capital Economics also estimates that ‘every additional pound of investment in construction would stimulate an extra £2.84 of economic output in supply chains and through the higher spending of employees, and an extra 56 pence of new tax revenues for the exchequer’.

Melanie Rees, head of policy at the Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH), tells Inside Housing: ‘The size of the benefit bill is a combination of low wages but also the short supply that’s fuelling high prices, so for us it makes sense to invest in supply and, over time, that would deliver better value for money.

‘We’ve also been arguing for some time that investing in social rented homes would stimulate the economy, so this report really reinforces what we [have] said.’

In the longer term, Capital Economics forecasts significant differences between the financial outcomes of the two policies over the next 50 years. Under the current policy, it predicts public sector net debt in 2065/66 would be 86% of GDP and the structural deficit would be 1.7% of national output.

Upfront contribution

However, under SHOUT’s proposed programme of building 100,000 new social homes per year, they estimate public sector net debt would be 5.2% less and the structural deficit 0.5% less, at 80.8% and 1.7% respectively.

In terms of implementation, the report states: ‘Increasing the stock of social rent housing requires investment by social landlords and some level of upfront contribution from the state’, and recommends a ‘realistic and practical policy’ of steadily building up to 100,000 new homes per year by 2020/21, since a step change in construction would not be possible overnight.

However, it’s the initial capital investment that’s likely to be a crucial concern for the spending-averse Treasury, and the report concedes that: ‘In the initial years, the incremental welfare savings and new tax receipts will be less than that needed to fund the government’s contribution to the new homes – so additional public sector borrowing will be required.’

Borrowing is expected to peak by 2019/20 at no more than 0.13% of GDP, with the policy expected to yield a net surplus for the public accounts by 2034/35.

Perhaps most significantly, from a broader economic perspective, Capital Economics suggests enhanced asset investment in social housing is not only ‘efficient fiscally’, but would also be welcomed by financial markets.

The research firm’s economic credentials within the global markets will likely lend weight to this element of the report.

‘We already know [subsidising rents instead of capital investment] is a false economy, but [the report makes] very interesting comments about the City’s likely tolerance of investment in housing,’ says SHOUT’s Martin Wheatley.

‘Far from saying the SHOUT proposal is irresponsible, they say markets would view it as a sensible policy. For us, this is about saying to a government that’s laying quite a lot of emphasis on fiscal responsibility that the cost of [their current policy] is a massive threat.’

Once built, the report adds, social housing effectively becomes self-funding through rents and provides additional social and economic benefits not captured by the fiscal analysis, such as improved health, well-being and education.

Though housing policy debates since May have largely focused on the government’s flagship Right to Buy policy, this report is likely to feed into ongoing sector debates around the relative merits of capital investment and rent subsidy.

Nick Horne, chief executive of housing association Knightstone, says: ‘We recognise the importance to the government of moving more people into homeownership, but the reality is there will always be a significant number of people for whom homeownership is not an option or preferred choice.

‘Housing associations are best placed, through government capital finance support, to deliver the number of social homes needed. Housing associations have a long record of terrific value for money in new housing supply and levering in private finance that maximises the taxpayer investment.’

Likewise, the National Housing Federation (NHF) backs the findings of the report. ‘Housing associations are hugely ambitious and are ready to build thousands more desperately needed affordable homes across the spectrum, from social rent to low-cost homeownership,’ says Kathleen Kelly, assistant director of policy and research at the NHF.

‘Our new government has committed to end the housing crisis within a generation. Now it must free up land and provide proper investment to help us make that happen.’

However, the government’s initial response to the report is not encouraging. Brandon Lewis, housing minister, says the existing affordable rent model ‘maximises the delivery of much-needed affordable housing, making the best possible use of constrained public subsidy’. Figures across the housing sector will be crossing their fingers and hoping that the case made in the report is eventually taken on board by ministers.

Policy assumptions

Current policy:

- Total of 31,500 units for social or affordable rent each year

- 5,500 social rent units are completed each year, of which 2,500 are built through section 106 contributions

- 25,000 affordable rent units are completed each year supported by government grant of £16,000 per unit

- 1,000 affordable rent units are completed each year without government grant through section 106 contributions

Exemplar policy:

- 100,000 social rent units are completed each year from 2020/21

- 24,500 of these are by local authorities or arm’s-length management organisations

- 85,000 are supported through government grant. We use our calculated requirement of £59,000 per unit as the level of grant

- 3,000 are built through section 106 contributions

- 20,000 social rent units house tenants who don’t receive housing benefit

Source: SHOUT, Building New Social Rent Homes