You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

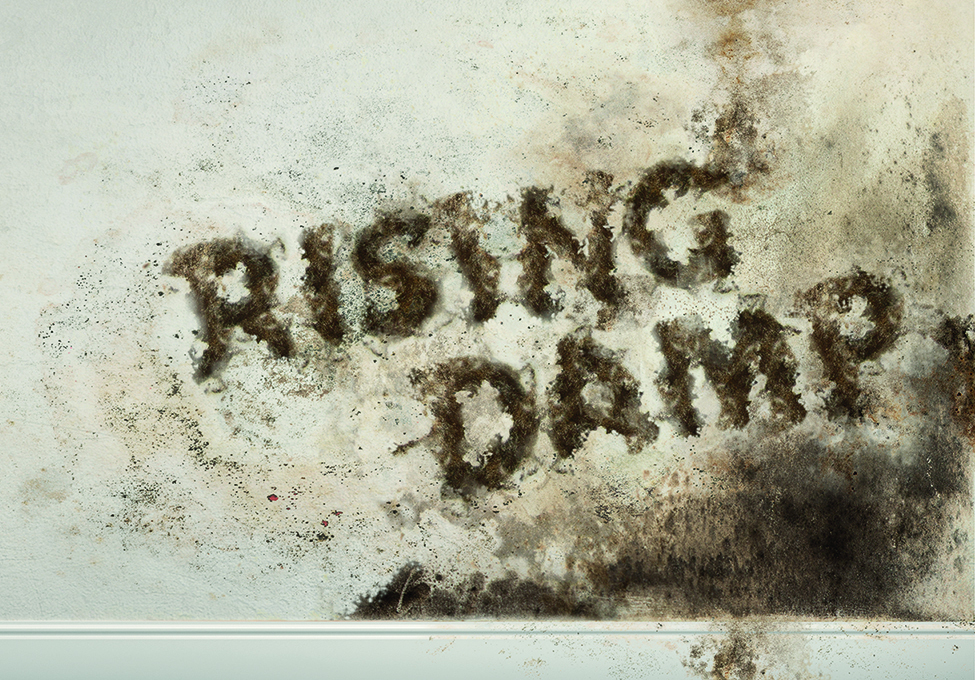

Rising Damp

Is energy efficiency work creating damp problems for social landlords and tenants? Jess McCabe finds out about the…

Video:

features style

Source: Spooky Pooka

When Dr Who called Britain a “damp little island”, millions of TV watchers will have nodded in agreement.

After all, a survey in 2014 carried out by Ipsos Mori for the Energy Saving Trust found that 38% of Britons complain of condensation, and 29% report problems with mould, which is often put down to Britain having some of the oldest and dampest housing stock in western Europe.

Then, this summer, a report by the Building Research Institute (BRI) put the sector on damp alert. Released to the BBC after a Freedom of Information request, the report set out how cavity wall insulation was leading to damp problems for Welsh social landlords and tenants. More than 2,000 Welsh social homes have had to have insulation ripped out of their cavity walls, it revealed. Newport City Homes, RCT Homes and Cartrefi Cymunedol Gwynedd are among the housing associations with afflicted homes, while a number of councils have also reported problems.

It’s not just the BRI that has been paying attention to this issue. In February this year, The Daily Telegraph published a column headlined: “Could the cavity wall insulation scandal rival PPI?” Meanwhile, the consumer press is full of homeowners’ horror stories of insulation gone wrong or installed in inappropriate walls, such as those exposed to lots of driving rain. An entire industry has grown up around extracting material from cavity walls to rectify their mistakes.

Many of the cases appear to be in new-build homes, or as a consequence of retrofitting older properties where the work has been poorly carried out or the homes have inadequate ventilation.

Social landlords, however, understandably want to continue with energy efficiency programmes that can help their tenants save money and improve their stock. So what can they do differently to prevent these problems in future?

Video:

Ad slot

These questions are serious enough to have prompted the government to take a look. Inside Housing understands the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) is undertaking research on how building standards could help prevent damp in new build homes.

And the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) has commissioned Peter Bonfield, chief executive of BRE, to lead a review of consumer protection issues around home energy efficiency, which is due to report next spring. Its remit is to “look at standards, consumer protection and enforcement of energy efficiency schemes and ensure that the system properly supports and protects consumers”, according to DECC, which did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

Subsidy faults

The industry itself is keen to stress that the cases of poor execution or insulation of inappropriate walls are a vanishingly small proportion of installations. Joanne Wade, director of the Association for the Conservation of Energy, says: “Our members are always concerned when they see stories of potentially low-quality installations. It’s a tiny, tiny number of complaints.”

Still, most landlords, surveyors and industry experts Inside Housing spoke to for this story reported problems. Many put at least some of the blame on the design of the government subsidy programme for energy efficiency work, the Energy Company Obligation (ECO), and its predecessors, known by their acronyms CERT and CESP. Like a building that has been poorly constructed, the argument goes, the policies have structural weaknesses that were almost certain to lead to the blight of damp, condensation and mould, putting residents’ health and landlords’ pocketbooks in danger.

ECO focuses on doing the most work for the smallest cost. The idea behind it was to encourage the mass application of insulation. Contracts are calculated based on tonnes of carbon dioxide saved, and work apportioned by the big energy companies in order to meet government-set targets for CO2 savings.

But the profit margin is tight. Surveyors told Inside Housing there is little incentive for an installer to inspect cavity walls before filling them with insulation, or ensure that there are no uninsulated ‘cold bridges’ between insulated walls and insulated roofs. This meant that they may have missed what Les Greene, responsive repairs team leader at Liverpool Housing Trust, calls “cement snot” – bits of the material stuck in the cavities of walls that prevent insulation being blown evenly through the wall, and which can draw water from the outer to the inner wall. Moisture in the air inevitably settles on these cold patches, creating a perfect environment for mould.

Some experts believe a complete rethink of policy is needed, namely a shift away from mass programmes of works towards smaller projects done thoroughly.

“The number of homes needs to be less to do it properly,” says Andrew Mellor, a partner at environmental consultancy PRP, who has also seen many examples of both new build and retrofit energy efficiency work gone wrong.

“Ventilation is not being considered as part of the ECO [or] Green Deal work,” he adds. “When I went to DECC and showed this happening, they were pretty alarmed.”

Self-regulation

Mike Parrett, a building pathologist who advises social landlords on how to diagnose damp problems (see box), says: “I’ve sat watching guys on regeneration sites. They come along with a big hose, drill a hole and pump it [insulation] in. Nobody is checking it. There are no building control officers anywhere. It’s a self-regulated industry.”

Ms Wade, of the Association for the Conservation of Energy, an organisation that represents both installers and manufacturers of insulation, also argues that the design of ECO, CESP and CERT has exacerbated the problem. But her argument is that the peaks and troughs of the subsidy system targets lead to a great volume of insulation jobs followed by an empty order book.

“Skilled people leave the industry because there’s no work,” says Ms Wade. Then, when the boom comes again, “it increases the chance of people who have not been well trained getting involved.”

It is important to remember that the problems are not just linked to ECO, CERT and CESP work. Shaun Kelly, sustainability manager at Peabody, explains that most of the association’s stock is free of major problems, although it has carried out a lot of insulation work. But the Thamesmead Estate in London, which became part of Peabody’s stock in 2014, does have a number of damp problems. Peabody is now working to address residual issues of poor wall and floor insulation and cold bridging.

Mr Kelly says: “Since the introduction of higher energy efficiency standards from 2006, there has been an increase across the UK in issues with condensation and mould, even in new homes. To meet energy-efficiency standards, new properties need to be pretty airtight and must be adequately ventilated.”

In Scotland, meanwhile, the problem does not seem to have occurred on the same scale. Inside Housing made a request under Environmental Information Regulations (EIR) – newly applied to Scottish housing associations – to find out the number of cases of damp in the past two financial years. The 63 housing associations that responded to the EIR request reported only 69 homes with damp problems severe enough for the property to fail the Scottish Housing Quality Standard (SHQS) during that period. All social housing should have met this standard by April 2015.

Stormy weather

The problems are not necessarily structural, either. Terry Frew, maintenance manager at Glasgow-based 1,200-home Elderpark Housing Association, reported none of its properties in 2013/14 or 2014/15 failed the SHQS. But it reported one of the highest number of cases of rising or penetrating damp (59 cases in 2013/14 and 73 the next year). Mr Frew puts the problem down to storm damage.

Tony Teasdale, director of Rural Stirling Housing Association, told us of one case in 2014/15, “which was caused by bridging from poorly completed remedial work during a cavity wall filling contract”. The problem was resolved as a defect under the contract.

This was the only mention of insulation-related problems when Inside Housing spoke to Scottish landlords.

Scottish landlords can apply for ECO funding. But they also have the option of applying for grants directly from the Scottish Government, which has set aside a total of £103m in 2015/16 for energy-efficiency schemes.

On top of this, housing associations themselves invested around £309m from March 2013 to March 2015 towards bringing their stock up to the SHQS. “If you don’t meet that standard, you have to make it very clear to them [the regulator] why you are not able to,” says Shirley Evans, a senior associate at law firm Anderson Strathern. And now the sector is working on meeting the next iteration of the standards, the Energy Efficiency Standard for Social Housing.

David Stewart, policy lead at the Scottish Federation of Housing Associations (SFHA), says these standards have promoted steady working towards the target over a number of years, and may have led to a reduction in problems. “It’s funded by landlords themselves. They’ve had quite a bit of quality control,” he says, adding that when they have undergone work under ECO, some SFHA members have engaged a clerk of works to check on the quality.

DECC and DCLG may have their eye on changes to policy and regulation that will avoid these problems in future.

But in the meantime, social landlords may wish to take heed of Mr Stewart’s solution: “Someone on site to inspect the work.”

Case study: Liverpool Housing Trust

Liverpool Housing Trust (LHT) says it is saving £200,000 a year after it invested in training and equipment to more accurately detect the causes of damp in its stock.

The 10,000-home trust changed its practices after finding it was needlessly spending money on treatments for failed damp-proof courses, when the problems being reported by tenants were caused by something else. (Damp-proof courses are a layer of waterproof material in the wall, close to the ground.)

Between August 2011 and August 2012, the trust spent more than £250,000 on damp work, which largely involved hiring a specialist damp contractor who would, more often than not, recommend a chemical should be injected into the damp-proof course. Les Greene, responsive repairs team leader at LHT, recalls how he started to notice the same properties were reporting damp problems even after this work had been carried out.

“I just started to ask some questions as to whether we were actually engaging professional contractors,” he says. And then he began to ask deeper questions about whether the problem was being correctly identified.

Then he saw a presentation about the overdiagnosis of damp-proof course failure, which featured a clip from a 1990s documentary called Raising the Roof. It included footage of surveyor Mike Parrett, who then worked for Lewisham Council, where he discovered the same problem. Mr Parrett believes that detailed diagnostic work should be done by independent surveyors, rather than companies that sell damp-proof course treatments, to identify the cause of damp.

Blockages of cavity walls are one of the common causes of damp Mr Parrett encounters. In one house, he found a donkey jacket hanging in the cavity. It was sodden, but in the pocket was a tobacco tin and non-decimal currency, suggesting the original bricklayer had hung it up and accidentally bricked it inside the wall.

LHT engaged Mr Parrett to provide training for the trust’s surveyors, and later a training firm called Cornerstone. The trust also bought equipment used to detect damp, such as thermal-imaging cameras, which if used correctly can show cold spots; borescopes, which allow the inspection of the wall through a small hole; and moisture testers and data loggers, which can be fixed to a wall to track information such as ambient temperature and wall temperature throughout the day and identify any patterns.

Three years after LHT changed its approach, it has reduced spending on measures to combat damp by 80%. Mr Greene has estimated that if other social landlords adopted the same approach, the sector could save £72m a year.