What Australia is doing to prevent a repeat of Grenfell

Grenfell has hastened an investigation into a tower block fire in Australia in 2014. What can the UK learn from its recommendations? Pete Apps reports

Melbourne is nine hours ahead of London, but in the unfolding saga over unsafe cladding on tower blocks, the time difference is more like two-and-a-half years.

It was November 2014 when a dropped cigarette started a fire on the eighth floor of the 23-storey Lacrosse building in the city’s Docklands. What happened next is grimly familiar. The flames took hold on the outside of the building and ripped upwards, reaching the roof in just 11 minutes.

Later, an investigation revealed the building had been fitted with aluminium cladding with a polyethylene core. When this cladding was tested for flame resistance a few months later, the test was abandoned after 93 seconds due to the ferocity of the flames.

Now, three years on, hastened by the disaster in London, the Australian Senate’s Economic References Committee – tasked with investigating the blaze – has published an interim report recommending several changes to avert a further disaster.

As the public inquiry into the Grenfell Tower fire gets underway this week, and a long-awaited look at building regulations also gears up for action, we look at what the UK sector should learn from the work already carried out on the other side of the world.

Broader focus

According to a fire safety engineer quoted in the committee report, a kilogram of polyethylene when burned will release the same amount of energy as one-and-a-half litres of petrol. Each square metre of the cladding has around three kilos of plastic in it, meaning each sheet is like attaching five litres of petrol to the outside of the building.

Lacrosse, unlike Grenfell, was a modern, newly built tower and the cladding was installed as part of the construction process. In common with Britain, building regulations prohibit the use of flammable material on tall buildings. Australia has found itself grappling with the same questions facing policymakers in Britain: how widespread is the use of this cladding? Why did the system of regulation fail? And what should be done to prevent it being used in the future?

In answer to the first, state governments are currently undertaking audits to establish the full extent of the problems. But Phil Dwyer, national president of the Builders Collective of Australia, believes it will prove to be widespread, telling the committee he estimated the full level as “tens of thousands of buildings”.

This may be another indication that Australia is further ahead of the UK in its response to the issues. While our government has a narrow focus on perceived problems in the social housing sector, the debate in Australia is broader. In Australia, explains Adam West, business development manager at the New South Wales Federation of Housing Associations, the social housing sector is much smaller and primarily made up of building managers rather than owners and developers, as is the case in the UK. The 31 social housing towers in New South Wales have been deemed safe.

“Cladding is being found mainly on private buildings and on hospitals, schools and universities, which is where that 10,000 figure is coming from,” he explains.

This may well reflect the final picture in the UK as well. Last week, the government quietly revealed that 85 of 89 privately owned cladded tower blocks had failed combustibility tests. So both countries appear to have an industry-wide issue to solve.

So what was wrong with the regulations to allow this to come to pass? The system of regulation, the report said, was “inadequate and too easily evaded”. Australian building regulations are contained in the National Construction Code. These are performance-based regulations, meaning that rather than ruling one type of product compliant or non-compliant, they set a performance standard which the building or system as a whole must achieve. This has the benefit of flexibility in a world where techniques, materials and new technologies are rapidly evolving – but it also opens the door to loopholes.

In particular, the committee heard evidence that the code can be “fragmented, confusing, lacking in definitions [and] contradictory”. This causes confusion in the industry, and there is a lack of oversight to ensure that builders are getting it right.

“You need qualified, trained people to understand how a performance-based code works,” says Neil Savery, general manager of the Australian Building Codes Board, which helps try and set consistent codes between various state territories. “At the same time [as the code was introduced] we had a process around the country of deregulation or reduction around regulatory requirements for things like mandatory inspections.”

All this is eerily similar to England. The building regulations’ Approved Document B was described as a “most difficult document to use” by the coroner investigating the fire at Lakanal House in London in 2009. Like Australian standards, they are performance based: apparently requiring materials of limited combustibility, but leaving enough room for industry bodies to sign off on lower-quality systems based on desktop studies.

In Australia, like England, there is no regulator or arm of government upholding standards. This effectively allows the building industry to pay a consultant to check their work. This is obviously not a system which creates the incentive for rigorous application of standards.

To overcome these issues, the senate committee recommended some tough changes.

The potential for professionals to misunderstand the complex building guidance led the committee to recommend a national licensing scheme for all trades and professionals involved in the building industry, which would require continual professional development. This would also allow those who breached regulations to be struck off – adding teeth to the regulations and removing the incentive to chance it with a cheaper product that may be borderline in terms of compliance.

It also called for mandatory on-site inspections by regulators throughout the construction process. “It is evident that there needs to be a central oversight role independent from the industry to provide assurance to the public,” the report says. It also called for mandatory inspections by fire authorities to ensure compliance and safety, specifically fire safety.

While these are recommendations that would undoubtedly send shock waves through the industry either in Australia or the UK, they are surely worth considering given what Grenfell has shown us about the high price for failure.

Zero tolerance

But improving the system of regulation is only half the battle. The real challenge is achieving compliance with those regulations and the Australian senate committee noted some real issues with how to deal with this in the context of the sometimes dubious nature of the building industry.

It noted that with many building products being imported from overseas, certificates are often unreliable or issued by companies which do not fully understand Australian standards. It also noted evidence that “fraudulent or misleading” product certification was rife.

Another problem, of which there have already been accusations in the UK, is product substitution. “Substitution occurs… when a builder or somebody involved in the purchasing process is looking to save money,” said one witness to the inquiry, with another warning it is “a major problem within the building industry”.

If unscrupulous contractors are willing to switch fire-resistant panels with the cheaper, lighter, plastic-cored material, the regulations do not matter. And so the senate committee felt it was necessary to go further. The report calls for “a total ban on the importation, sale and use of polyethylene core aluminium composite panels as a matter of urgency”.

While it recognised that there are legitimate uses for the panels, particularly in the context of signage, the best way to ensure they never end up on the outside of tall buildings is to stop them coming into the country altogether.

“Once it’s in, once it’s past the port and into the distribution network, chasing it, catching it and identifying it particularly after it’s been used is an absolutely massive task and one for which, quite frankly, nobody is adequately resourced,” John Rau, deputy premier of South Australia, told the committee.

There are other questions for UK policymakers arising from the Lacrosse building fire. For example, there were no major injuries or deaths in the blaze – a fact which fire fighters put down to the tower’s sprinkler system and the rapid evacuation of the building, neither of which were present at Grenfell.

Pertinently, there is also the question of why our country did not sit up and take notice of what was happening in Australia earlier. The combustibility testing showed polyethylene aluminium panels were combustible in February 2016 – two months before the refurbishment work which installed them on Grenfell completed and more than a year before the fire. Given the evidence, as at least one witness to the senate committee stressed, the disaster at Grenfell was “not only preventable but avoidable”.

It is too late to correct the damage from this missed warning. But policymakers in this country could do worse than following the Australian recommendation and immediately banning polyethylene-cored panels here as well. After all, cladding burns the same in the southern hemisphere as it does in the north.

Key recommendations from Australia’s senate committee report

- A total ban on the importation, sale and use of polyethylene core aluminium composite panels as a matter of urgency

- A national licensing scheme for building industry professionals

- Central oversight role from independent regulator to ensure buildings are built to required standards

- Penalties for non-compliance including revocation of accreditation, ban from tendering and ‘substantial’ financial penalties

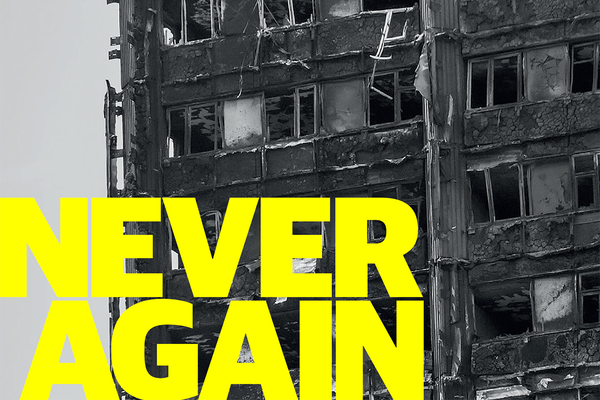

Never Again campaign

Inside Housing has launched a campaign to improve fire safety following the Grenfell Tower fire

Never Again: campaign asks

Inside Housing is calling for immediate action to implement the learning from the Lakanal House fire, and a commitment to act – without delay – on learning from the Grenfell Tower tragedy as it becomes available.

LANDLORDS

- Take immediate action to check cladding and external panels on tower blocks and take prompt, appropriate action to remedy any problems

- Update risk assessments using an appropriate, qualified expert.

- Commit to renewing assessments annually and after major repair or cladding work is carried out

- Review and update evacuation policies and ‘stay put’ advice in light of risk assessments, and communicate clearly to residents

GOVERNMENT

- Provide urgent advice on the installation and upkeep of external insulation

- Update and clarify building regulations immediately – with a commitment to update if additional learning emerges at a later date from the Grenfell inquiry

- Fund the retrofitting of sprinkler systems in all tower blocks across the UK (except where there are specific structural reasons not to do so)

We will submit evidence from our research to the Grenfell public inquiry.

The inquiry should look at why opportunities to implement learning that could have prevented the fire were missed, in order to ensure similar opportunities are acted on in the future.