Cause and effect

Each year the Chartered Institute of Housing’s UK housing review analyses the trends in social housing. Here Hal Pawson, Steve Wilcox and John Perry give a sneak preview of this year’s report, which looks at the impact major government reforms will have on the sector.

For almost 20 years the Chartered Institute of Housing’s annual UK housing review has been analysing changes in housing policy.

The latest review, published this month, marks a peak in social housing investment. Figures show that the past two years saw the highest sustained level of social housing investment in real terms for three decades. It also provides a detailed scrutiny of the coalition government’s radical policy reforms, benefit cuts and spending reductions set to impact UK housing in the coming weeks and months.

As well as collecting statistics and summarising trends, the review also raises some important questions. This year’s include:

- How did the last government’s avowed aspiration for improved public services play out in social housing?

- What are the barriers now facing first-time buyers?

- How will the coalition’s changes to housing benefit affect low-income tenants?

- How will housing be affected by the ambitious proposals of secretary of state for work and pensions Iain Duncan Smith to rip up and replace the current benefit system?

Here we summarise the report’s conclusions.

Housing benefit changes

The review assesses the likely impact of the government’s proposed housing benefit changes for the private rented sector. It also looks at the new ‘total’ benefit cap that is to apply to working age households that are not working, across all tenures, and the impact of benefit limits on the new ‘affordable’ rents that associations will be able to apply to new lettings.

While in the past intermediate rented housing fell between social rented and private rented housing at market rates and was targeted at households with intermediate incomes, it will now be provided for all households unable to secure market housing.

Landlords will be able to set rents at 80 per cent of local market rates, provided this amount is not greater than local housing allowance rates for the private rented sector which will no longer be calculated by finding the median average of local rents, but by finding the 30th percentile instead.

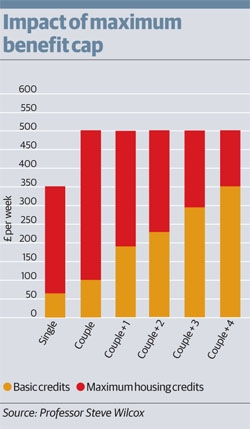

If LHA rates and national caps will constrain intermediate rents for affordable housing in many cases, the resulting rents are still often beyond the reach of out-of-work families with children, following the introduction of the new total benefit caps for out-of-work households. The new maximum levels based on current benefit levels are shown on the graph: Impact of maximum benefit cap.

In effect, the limits will restrict total help with housing costs (council tax as well as rents) to £265 for a couple with two children, £207 for one with three children, and just £150 for a couple with four children.

These are clearly much lower than the LHA caps, and will further hamper opportunities for out-of-work households to secure private rented accommodation. But in higher value areas they will also put intermediate rents beyond their reach. Given that more than half of working age households allocated social sector dwellings are currently not in work, this will have a major impact - especially in high-value areas like London.

Families with two children who are not working will not be able to afford intermediate rent tenancies in inner London. Those with three or more children will be unable to afford them anywhere in London or in many other high-value areas. For very large families the implications are even more dramatic - they will only be able to afford even existing social sector rent levels by making substantial contributions from the incomes previously available to them for their other living costs.

Such severe limits will clearly provide strong incentives for families to work, if only to the minimum level required to avoid the benefit caps. Social sector landlords looking to maintain their purpose, and to protect their revenues, will also need to consider how they can best assist families to meet the minimum work requirement. Tackling worklessness suddenly becomes a financial as well as social imperative for landlords.

Performance dividends

For most UK social landlords, the past seven to eight years have seen a marked upturn in housing management performance. The review reveals this period has witnessed fairly steadily improving void management, rent arrears control and responsive repairs in England and Scotland.

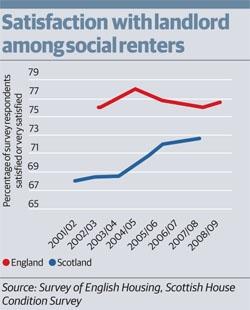

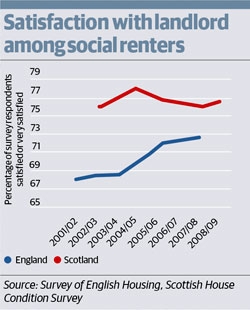

However, traditional performance indicators alone tell us little about service quality as seen from the consumer perspective. So it is particularly good news for landlords in England that 2001 to 2009 also saw a rising trend in tenant satisfaction as tracked by government surveys. Although a relatively modest 4 per cent, the increase should be seen against a wider backdrop of rising social expectations: service providers probably need to continually up their game even to stand still in their satisfaction ratings.

Equally, as the graph shows, English providers still have some way to go before their scores equal those in Scotland. Nevertheless, Scottish social landlords may see the slightly flatter recent trend among their tenants as a little disappointing.

An important likely contributor to satisfaction trends in England is the ongoing progress of the decent homes programme. While spending cuts mean its completion will now be delayed, the review confirms that the programme has been linked with a dramatic threefold real-term increase in council housing investment since the late 1990s, peaking in 2007/08.

Tenant satisfaction ratings were taken increasingly seriously by the Audit Commission when making judgements on individual landlords. But coalition government ministers have signalled that they don’t think it is important for social landlords to measure tenant satisfaction against a nationally consistent standard. Particularly at a time when regulatory inspection is being wound down, there must be a risk that these changes will lead social landlords to downgrade ‘service delivery excellence’ as a key corporate priority.

The government is on the point of dismantling many elements of a system that has delivered both improvements and the evidence of their positive outcomes. Whether the new localist agenda will work as effectively, and how the data to make such judgements will be collected, remains to be seen.

First time buyers

The collapse in the availability of mortgages requiring only a small deposit is now the largest single barrier facing households aspiring to homeownership, says the review.

In 2009 there were just 28,000 mortgage advances to first-time buyers that did not need a deposit of more than 10 per cent. This compares with 245,000 in 2006. Last year saw a further decline in the availability of low-deposit mortgages. An average 10 per cent deposit for a UK first-time buyer in 2010 was £18,600; in London the average was £29,700.

The number of young first-time buyers able to buy without using the ‘bank of mum and dad’ or other assistance with a deposit fell by 100,000 a year between 2006 and 2009. The numbers purchasing with help of that sort stayed constant - but by 2009 they had become 80 per cent of all younger buyers.

While part of the decline in availability of low-deposit mortgages is cyclical, it is now being reinforced by the overall shortage of mortgage finance. And this is set to become entrenched by an overly cautious regulatory regime planned by the Financial Services Authority. This is despite FSA evidence that low-deposit mortgages, in themselves, are not significantly more risky.

The evidence does make a case for tighter regulation of various kinds of high-risk products, and on mortgage advances of more than 100 per cent of purchase price - but not for drastic restrictions on low-deposit mortgages for households with adequate incomes and a satisfactory credit history.

The notion that younger households can bide their time and save their deposit while renting for a few years flies in the face of the evidence of the very low savings rates of younger households. Indeed, the only significant savings achieved by younger households in recent decades has been through the growth in value of their homes after becoming homeowners. At the same time they continue to aspire to homeownership in the medium and long term: many view private renting as ‘throwing money away’.

The review finds the ‘deposit barrier’ is now by far the biggest obstacle facing households aspiring to be homeowners. The deposit barrier is socially uneven. It impacts most on households without parents or friends that can assist with a deposit: a barrier to social mobility.

This is an area with potential for positive government intervention. It should pull the FSA back from an unnecessarily restrictive regulatory regime for low-deposit mortgages. It should promote the availability of mortgage guarantees as a mechanism for providing both households and the financial sector with greater security for low-deposit mortgages. Without such action there will be continuing decline in homeownership in the UK, and rising frustration among younger households trapped in the rented sector against their will.

Universal credit

The immediate challenges facing the sector come from the housing benefit reforms, however, work and pensions secretary Iain Duncan Smith’s wider revamp of the entire welfare benefits structure is also looming. This will include changes to the help that low-income households receive with their housing costs.

The government’s plans are radical and ambitious. If carried through, they will bring the most significant changes to the welfare system for 40 years. At the centre is the unification of current benefits for households in and out of work, to create a single ‘universal credit’.

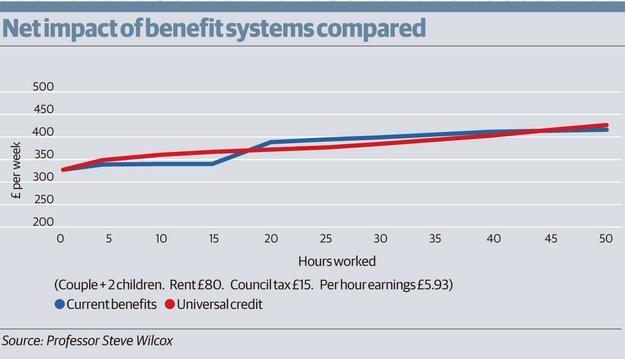

The changes are not just an administrative simplification. They aim to both improve work incentives and make the potential gains to households entering low-paid work more evident. Key to this is the single (65 per cent) ‘taper rate’ through which the universal credit is withdrawn as a household’s earned income rises. This will replace the complex overlapping tapers of tax credits and housing benefits that dog the present system - which can result in households losing as much as 96p in benefits for every £1 of extra earnings.

Just how the universal credit will compare to the current benefits structure will depend on the final details. The government expects the new system to be introduced in 2013. The potential impacts on household earnings are shown in the graph: Net impact of benefit systems compared. As an overall concept, universal credit has been broadly welcomed, but some aspects are problematic - none more so than plans to restructure help with housing costs.

The good news is that universal credit is planned to include help with homeowners’ mortgage interest costs, as well as tenants’ rents. This could be a major step towards a more tenure-neutral welfare system - all the more so if it removes the two-year time limit that applies to new claims under the current support for mortgage interest scheme available for out-of-work, homeowners.

However, there is a snag. Households getting help with housing costs will have their ‘earnings disregard’ - a small amount of earnings not taken into account in assessing whether they can pay their rent - reduced by a multiple of 1.5 times the eligible costs. There will be a ‘floor’ of minimum earnings disregards for those with higher levels of housing costs. This means that the positive financial incentives from the scheme, for households which have housing costs, will be less than those with no (or very limited) housing costs.

The fact that this is hard to explain is also part of the problem: the highly complex arrangements cut across the desire for a simple and transparent scheme that not only provides work incentives, but clearly delivers the message that ‘work pays’.

It will be very interesting to see whether the detailed proposals consider the anomalies that could arise with housing costs. Failure to do this would undermine the comprehensive nature of the reform.