You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

CIH chief executive interview: ‘You don’t choose the hand you are dealt’

Gavin Smart was only a few months into his new job as chief executive of the Chartered Institute of Housing when the COVID-19 pandemic struck. In his first major interview, he opens up to Martin Hilditch about the financial impact on the organisation and his plans for its recovery

Gavin Smart was just a few months into his new job as chief executive of the Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH) when the world changed.

At the start of lockdown, isolating from his family because he was feeling ill, he found himself running the CIH (and the rest of his life) from a motor home parked on his drive. As the UK shut down, the CIH’s projected £500,000 annual surplus – its first for a number of years – evaporated as the organisation cancelled or postponed events, including conferences and face-to-face training, and the value of its reserves slumped as the stock markets tanked.

For a first-time chief executive looking to make his mark, it has been about as tricky a start as you could imagine.

“It is always a big step up anyway,” Mr Smart says candidly. “But to step up and then immediately have this land on your desk is obviously a huge challenge. I’m sure that I would have preferred a simpler, more normal environment. But you don’t choose the hand you are dealt.”

Mr Smart chats via Zoom from the Northamptonshire home he shares with four generations of his family, along with “two dogs, six chickens and two geese”. The aim is to find out how he plans to guide the CIH through the current difficult times, his thoughts on what the priorities should be for the rest of the sector and a bit more about what makes Mr Smart tick.

He is certainly already a familiar figure to most people in the industry, having worked in a variety of policy and research roles for a quarter of a century. This includes an “extraordinary apprenticeship in housing” at University of Bristol’s School for Advanced Urban Studies, two stints at the National Housing Federation (NHF) and his most recent job as deputy chief executive of the CIH.

In normal times this would all count as fantastic preparation for the top job. This, though, is an environment that has kicked sand in everybody’s face, irrespective of experience. How, then, has Mr Smart been looking to guide the CIH’s recovery in an unprecedented situation?

For a start, the response has involved making some pretty hefty savings. “We put in place plans to make £850,000 worth of savings across the course of the year,” Mr Smart states. “Which for an organisation of our size is a lot.

“Even with that, we would expect to produce a small loss. But we are all focused now on aiming to outperform those plans. But what we did was deliver a reasonable worst-case scenario. There is no point hoping for the best. You have got to plan for the worst and then you have got to outperform it. And so far we are actually ahead of where we said we would be.”

What has that worst-case scenario meant for the organisation? While there have not been any redundancies, about a quarter of the CIH’s staff were placed on the government’s furlough scheme. “It would have been difficult to manage without it,” Mr Smart states. Recruitment has been “minimised” and all staff have been working from home, saving on the usual travel and venue costs.

Investment in areas “unlikely to produce a significant income this year” have been “slowed” to reduce the cost burden. This includes work to create an online platform to help housing professionals assess their performance against the CIH’s forthcoming standards framework which will help professionals build their knowledge, skills and ethical approach. “It’s a medium-term investment that will produce returns in the medium term, but it is unlikely to produce a lot this year and we have to be cautious,” he adds.

“There is no point hoping for the best. You have got to plan for the worst and then you have got to outperform it”

Of course, for those placed on furlough and people facing increased workloads, it has been an incredibly tough time. Picking his words carefully, Mr Smart says he has tried to be as open as possible with colleagues. “The only way anybody is going to get through this is by working together and being clear and honest and transparent with each other,” he states.

“I need to be careful about how I say this because it will either come across as pompous or deluded – we try hard to be an organisation that is kind,” he adds.

“Being kind doesn’t always mean doing the easiest thing, because being kind can mean telling your colleagues something they need to hear.” But, he adds: “I think we have worked quite hard to keep sight of that during everything we have done.”

Whether he has succeeded or not, it is difficult to imagine that the thoughtful and earnest Mr Smart has not been agonising over the calls he has made.

Alongside all the internal change, there has been the small matter of keeping the show on the road externally, too. Mr Smart defines the CIH’s raison d’être as being there to provide support for members; training, educating and qualifying the housing profession; and to be the “public voice of housing through our policy work”.

“We have to make sure that now more than ever we focus on those,” he adds.

In terms of the public voice of housing, one of the key pieces of activity in recent months has been the launch of the Homes at the Heart campaign, led by a coalition of organisations including the CIH, NHF, National Federation of ALMOs and the Association of Retained Council Housing.

The central aim is to push for the delivery of more social housing in response to the pandemic. It is a broad coalition and Mr Smart says that he “can’t stress how important it is to me and all of the partner organisations that we have come together as housing. It is not five separate campaigns – it is one call”.

For Mr Smart, the campaign is needed because the pandemic has “laid bare the failings of our housing system”.

“The way that we have treated some of the people who have been most important to us as a country during the pandemic and the way some communities have been treated historically isn’t right and we should be able to do better,” he states.

The desired outcome would be for governments to have a clear plan to “make sure that everyone is safely, securely and affordably housed”, he adds.

While building more social housing is one solution, welfare reform is also urgently needed, Mr Smart states.

“The welfare system is working against some of the targets I set out in terms of security, in terms of affordability – it doesn’t help deliver that,” he says.

“For it to be a good home, we need to be thinking about not only matters of speed and financial efficiency, we also need to be thinking about quality and about safety and security. And, I think, the evidence is that too much that has come out of permitted development doesn’t look very good in that light”

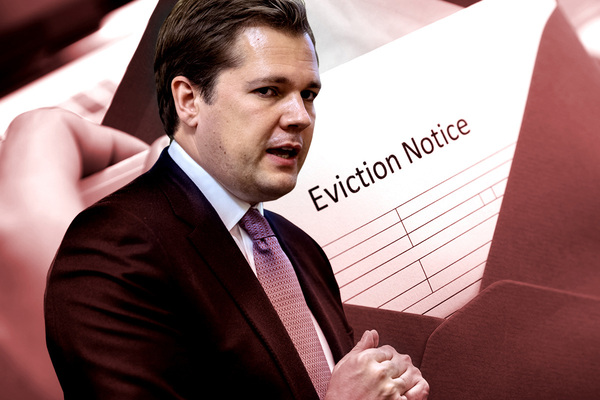

The failings of the current system could be catastrophically exposed later this month when the moratorium on evictions in England comes to an end, he adds.

“There is a risk that people who, through no fault of their own, have been placed in a difficult position because of the impact of the pandemic” may lose their homes because of the system’s shortcomings, he explains. “And that can’t be right.”

One of the government’s proposals for driving more housebuilding has been its decision to expand the use of permitted develop rights (PDR) – to allow the demolition and replacement of existing commercial buildings and upwards extensions with limited planning oversight. It is a decision Mr Smart has serious concerns about.

“We are talking about making people’s homes,” he says. “For it to be a good home, we need to be thinking about not only matters of speed and financial efficiency, we also need to be thinking about quality and about safety and security. And, I think, the evidence is that too much that has come out of permitted development doesn’t look very good in that light. Is anybody ever really suggesting that we should build homes that are as small as some of the homes that have been created under PDR?”

There is much work to be done, then. Mr Smart might not have chosen the hand he was dealt, but he remains optimistic about the chances of success.

“It is our job to rise to the challenge,” he concludes.

Gavin Smart is speaking at the Virtual Housing Festival on Monday 7 September at 11.45am