You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Five graphs that show where progress is stalling on removing dangerous cladding

Luke Barratt and Jessica Browne-Swinburne analyse the latest data on building owners replacing dangerous cladding.

Since the Grenfell Tower fire in June 2017, which killed 72 people, the spotlight has been on buildings covered in cladding made from aluminium composite material (ACM).

In the fallout from the tragic fire, a number of experts have agreed that the cladding played a major role in the spread of flames up the side of the building.

Indeed, Professor Luke Bisby, expert witness to the Grenfell Tower Inquiry, confirmed last year that the ACM cladding was “the primary cause” of the rapid spread of fire up the outside of the tower.

It therefore made sense that immediately after the fire, attention turned to other buildings covered in the same material and advice to remove this dangerous ACM from these buildings was be given.

The government has for some time been providing monthly updates on how work removing ACM cladding is progressing. Since September last year, this data has been more detailed and Inside Housing has broken the results down into five graphs to show where progress is stalling:

Three months after Grenfell, then-communities secretary Sajid Javid asked the Housing 2017 conference: “In one of the richest, most privileged corners of the UK – the world, even – would a fire like this have happened in a privately owned block of luxury flats?”

He suggested the answer was “no”, but figures have since shown that private buildings are actually more likely than social housing to be covered in ACM cladding.

Current government figures reveal that the private sector dwarfs the social sector in overall numbers, although its figures are split between private residential blocks – the most common ACM-clad buildings – and hotels or student accommodation.

Here, the numbers are reversed. Building owners have removed ACM cladding from around a third of all social housing blocks and hotels and students accommodation that required work.

For private blocks, though, owners and developers have managed to remove dangerous cladding from a woeful 6% of blocks. Almost two years after Grenfell, these figures make worrying reading.

The social sector, of course, is not exempt. A majority of blocks, according to these numbers, still have work to be done.

When you consider that in a government test fire spread to the top of a model wall of ACM cladding in less than seven minutes, the potential implications of this slow progress are truly terrifying.

This chart makes a similar point: showing how much more quickly the number of social blocks where ACM has been replaced has increased, while the number of private blocks has remained relatively static.

Our figures start four months after the government promised it would fully fund the replacement of ACM cladding on social housing blocks above 18 metres in height, which could explain why the pace is so much better for this tenure.

The speed of replacement for hotels and student accommodation has also been relatively fast. This could be explained by the greater rate of turnover in this type of accommodation.

People who stay in hotels and students have a greater level of choice than those living in ordinary residential blocks and so building owners have more incentive to make them safe.

So then progress in replacing cladding on private blocks is clearly the most pressing issue – due to the slow pace so far. The government, as one would expect, has been putting pressure on developers and building owners to resolve it.

Official figures have generally listed the number of owners who have plans to remove cladding as “unclear”, and this graph shows how over time those owners have moved into the column representing those who have expressed an intent to create a plan and, eventually, into putting a plan in place.

In January, Theresa May revealed that this process has not been quite as smooth as this might sound, describing owners with plans “unclear” as “refusing” to remove dangerous cladding.

Whatever the status of these owners, this graph shows that the government’s efforts have managed to reduce the numbers fairly significantly since last September, although in the past few months the number of blocks still without removal plans have stayed flat.

Of course, it won’t be much comfort to people living in ACM-clad buildings that owners are setting out plans to remove the cladding if nothing is actually being done.

And that, unfortunately, is what the figures reveal. This graph again shows the reasonably steady increase in the number of building owners with plans in place, but the numbers of owners who have either started or finished work does not change with it.

The inescapable conclusion is that while building owners may be showing government their plans to remove dangerous cladding, these plans are seldom translating into concrete action.

It’s difficult not to think that this must be linked to the dispute over responsibility. Owners know how to remove dangerous cladding but no one can agree who should pay for it.

Ministers have repeatedly said they will “rule nothing out” in response to owners who won’t remove dangerous cladding, but these threats seem to have fallen on deaf ears, with one building owner describing government plans to force them to pay for the work as a “hollow threat”.

The figures show that when the government provided direct funding, owners of social housing blocks replaced dangerous cladding. Perhaps it’s time for it to do the same in the private sector.

The Paper Trail: The Failure of Building Regulations

Read our in-depth investigation into how building regulations have changed over time and how this may have contributed to the Grenfell Tower fire:

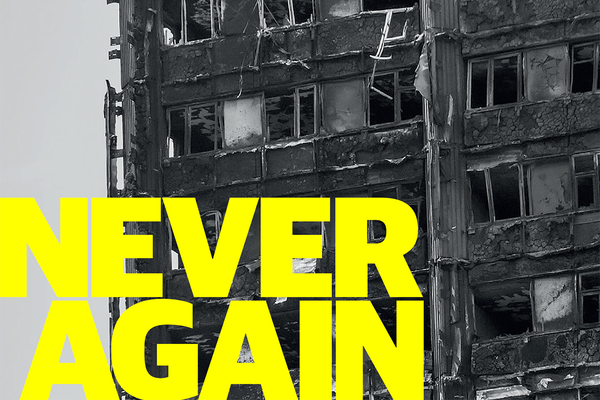

Never Again campaign

Inside Housing has launched a campaign to improve fire safety following the Grenfell Tower fire

Never Again: campaign asks

Inside Housing is calling for immediate action to implement the learning from the Lakanal House fire, and a commitment to act – without delay – on learning from the Grenfell Tower tragedy as it becomes available.

LANDLORDS

- Take immediate action to check cladding and external panels on tower blocks and take prompt, appropriate action to remedy any problems

- Update risk assessments using an appropriate, qualified expert.

- Commit to renewing assessments annually and after major repair or cladding work is carried out

- Review and update evacuation policies and ‘stay put’ advice in light of risk assessments, and communicate clearly to residents

GOVERNMENT

- Provide urgent advice on the installation and upkeep of external insulation

- Update and clarify building regulations immediately – with a commitment to update if additional learning emerges at a later date from the Grenfell inquiry

- Fund the retrofitting of sprinkler systems in all tower blocks across the UK (except where there are specific structural reasons not to do so)

We will submit evidence from our research to the Grenfell public inquiry.

The inquiry should look at why opportunities to implement learning that could have prevented the fire were missed, in order to ensure similar opportunities are acted on in the future.