You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

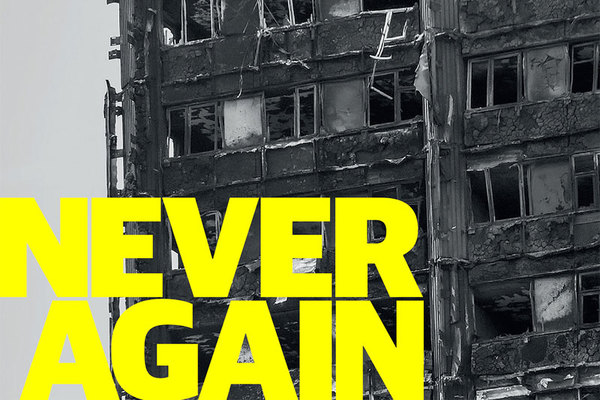

Housed too high?

The Grenfell tragedy has prompted questions over whether landlords should review the allocation of high-rise flats to older and disabled people. David Blackman investigates

When he was a rookie housing officer at Kensington and Chelsea Council in the late 1970s, Tony Bird let out flats at Grenfell Tower, which at the time was a new block. In those days, he says, it was standard practice not to let out homes to disabled people above the fourth floor in such blocks, or to families with young children.

These days, it is a different picture, says Mr Bird, who has kept in touch with North Kensington residents through his work as a tenant participation consultant. “Councils have quietly dropped their policies for younger children and disabled people above the fourth floor,” he says.

That point was underlined in the aftermath of last month’s disaster at Grenfell Tower, as it rapidly emerged that several of the fire’s suspected victims were disabled.

They included Sakineh Afrasehabi, whose daughter Nazanin Aghlani told the BBC that her mother had recently moved to a flat on one of Grenfell’s upper storeys that was only accessible by a 40-step flight of stairs.

A spokesperson for Kensington and Chelsea Council says: “We do not make direct offers of properties above fourth floor level in lifted blocks in the cases of people with disability access needs. However, through the council’s choice-based letting system, Home Connections, housing applicants are able to choose to bid on lifted properties located on higher floors.”

He says Home Connections, which operates across London, does not have an allocations policy and if someone chooses to bid for a property on a higher floor, it is their decision.

Another tenant, Flora Neda, only survived after being carried out of the block by her 24-year-old son, Shekeb. And the death toll of disabled residents could increase, according to Emma Dent Coad, the recently elected Labour MP for Kensington and Chelsea, who says several disabled residents remain unaccounted for. “One survivor who was physically dragged out of the building said there were two old men on his floor and neither has appeared,” she tells Inside Housing. It wasn’t easy for anybody to escape from the block, points out Sue Caro, an organiser of the Justice 4 Grenfell campaign. “There was only one staircase so everybody had difficulty getting out,” she says.

However, the difficulties of escaping from the blaze were exacerbated for those with limited or no mobility. The disaster has prompted questions as to whether social landlords should review the allocation of high-rise flats to older and disabled people. As it stands, such decisions are left to landlords – or individuals bidding through choice-based lettings systems.

“Councils have quietly dropped their policies for children and disabled people above the fourth floor.”

Sovereign Housing Association has no restrictions within its lettings policy for its taller buildings. It has 16 blocks over six storeys high. However, the 55,000-home landlord may apply local lettings plans, which can stipulate allocations restrictions for a particular scheme or block such as allowing no children aged under 10 above the ground floor, or restricting the property to those who can use the stairs.

“We don’t believe we need to change our policy at this time,” says a spokesperson. “Our existing approach means we work hard to make our buildings safe places to live, our potential residents have all the information they need to make an informed choice and we can make informed decisions based on the needs of the applicant on a case-by-case basis.”

The Fire Brigades Union does not have a specific policy on housing older or disabled people in high-rise blocks, but Dave Green, national officer at the union, says “it would certainly seem prudent to avoid putting frail, vulnerable people in high-rise housing as they would be virtually housebound if the lift broke down”.

He adds: “They are obviously going to face severe challenges should a fire break out, and we hardly need reminding of the horrors faced by those who lived in the upper part of Grenfell Tower. To put a vulnerable person with mobility issues or dementia in a tower block would clearly be best avoided.”

Draconian policies

But echoing Mr Bird’s observation, Pat Mason, a Labour councillor for Golborne ward, which neighbours the ward covering Grenfell Tower, says local authorities’ ability to earmark different properties for different groups is a lot more limited than when he became a councillor 26 years ago. “Councils used to have the ability to choose not to put partygoers beside older people but as the housing crisis bit, people going to the housing desk were allocated the very next property, whatever it was,” he says.

He argues that the people in housing need will be deeply reluctant to turn a tenancy down. “If you’re a 69-year-old person and you were offered the 15th floor of Grenfell, you were going to take it: you were going to be homeless otherwise,” he says.

A spokesperson for east London-based Poplar Harca, which has 23 tower blocks, has had a “few enquiries from families worried that mobility or health issues leave them more at risk if a fire should happen in their home or block”. They added that the 9,000-home association had completed a compliance check of its blocks and hand-delivered fire safety leaflets to all of its homes before lunchtime on the day of the fire.

The spokesperson says that local authority planners sometimes require fully accessible homes to be pepper-potted throughout even the tallest new buildings. In practice, families requiring fully accessible homes tend to wait for something lower, preferably on the ground floor, to become available, she adds.

Debbie Larner, head of practice at the Chartered Institute of Housing, cautions that it is important to put even a tragedy like Grenfell Tower into perspective.

“Something went horribly wrong at Grenfell,” she says. “We have fires in tower blocks on a weekly basis which are dealt with. We have to be really careful about being knee jerk [in terms of reactions] and changing things fundamentally across the board,” she says, pointing to the logistical problems that could be thrown up by having to regularly reassess whether a particular property remains appropriate for a particular individual.

Some of the disabled people living on the upper floors of blocks were not disabled when they moved in. And older tenants will often be reluctant to be uprooted from their family home.

Nevertheless, Ms Larner says that following such an appalling tragedy it is right to undertake a “pragmatic and sensible” reassessment of existing practice. “I don’t think we would ever have a blanket approach which says you will never house a person with a certain vulnerability or disability in a certain type of accommodation but you might want to rethink if there is only one access point.”

“To put a person with mobility issues in a tower block would be best avoided.”

Robust management is perhaps more a pertinent issue than allocation. “One of the lessons of Grenfell is that we don’t know who was in there,” says Ms Larner, noting the consequences of the Right to Buy, which means that many flats will be sublet by leaseholders. “The number of people probably living in that property compared to when it was built has increased significantly.”

Ms Larner, who has been liaising extensively with fire chiefs over the past few weeks, says the disaster has reinforced the importance of carrying out regular fire risk assessments of blocks, which should help the landlord to identify vulnerable individuals and how they can be evacuated in the event of a fire.

Wider problem

The Sovereign spokesperson insists the association has up-to-date fire risk assessments for its taller buildings and works with the fire service to ensure its approach to fire prevention and safety is robust. The Poplar Harca spokesperson says it draws up individual emergency plans for more vulnerable households, which will be shared with the London Fire Brigade when needed, to aid rescue efforts.

Fire risk is an ever-present hazard when running housing projects, says Bruce Moore, chief executive of 19,000-home Housing & Care 21, which houses a number of older people in high-rise blocks. “The question is whether they are controlled and spotted – those are the things we continually monitor and test,” he says.

“We are very clear about buggies not being in corridors, which could create a fire hazard if they are left in places they shouldn’t be, and storing things in corridors. This is a reminder about the necessary reasons we have those rules and regulations.”

For Ms Dent Coad, focusing on allocations is too narrow given the wider issues raised by the Grenfell disaster. “If a building is properly designed and maintained in the first place, it shouldn’t be a problem, but the problem is that they are not.”

Nick Raynsford, former housing and fire service minister, agrees the focus of the investigation has to be on “why fire stopping failed so disastrously, how effective the building control was, and all the issues about why the fire escape filled with smoke”. But he admits the fire raises questions about allocations and “whether you forcibly move people”.

Whether it is right or wrong to house disabled individuals on upper floors, a shortage of social housing means landlords have extremely limited room for manoeuvre. A spokesperson for Bristol Council, which has 59 tower blocks providing 4,334 of its overall 27,000 homes, says: “There is a massive shortage of accommodation in Bristol and tower blocks provide a significant percentage of available social housing.”

Ms Larner agrees it is a more fundamental problem than simply allocations. “Like everything else does, it goes back to supply,” she says.