You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

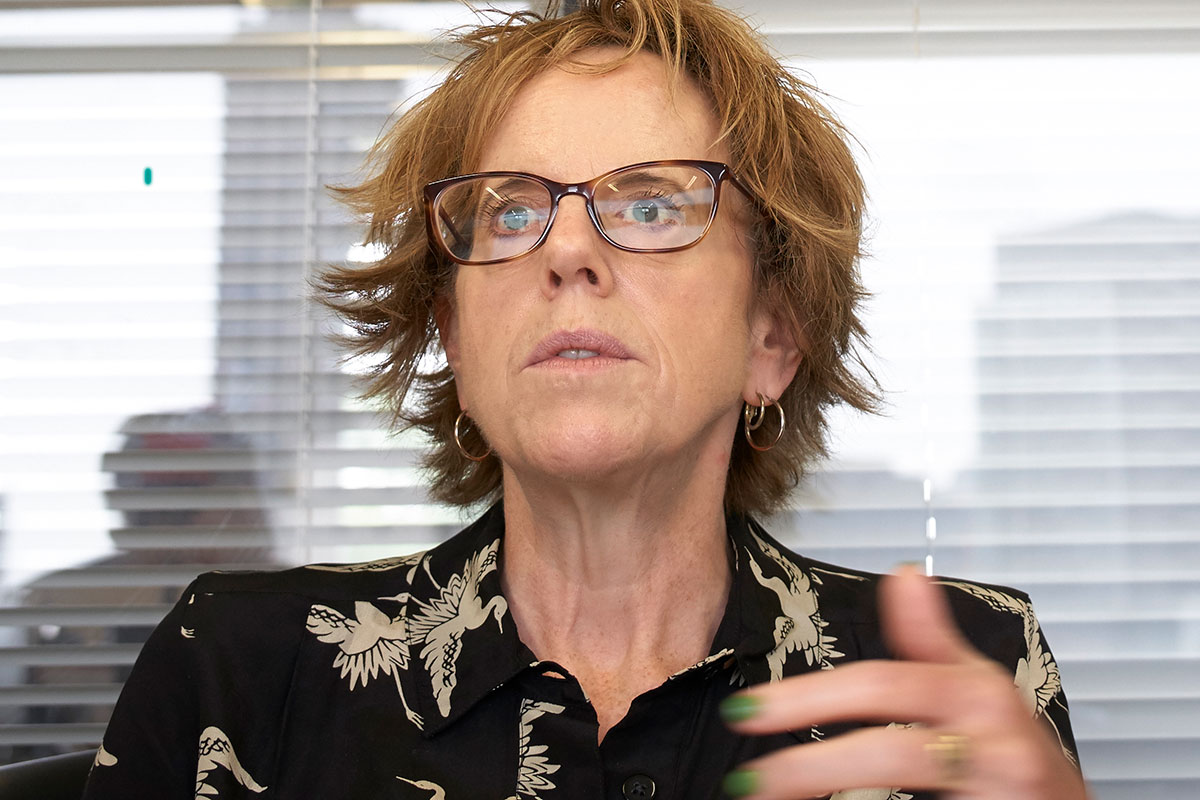

Interview with Polly Neate: we need to talk about social housing

Shelter’s chief executive Polly Neate is worried about the state of social housing. Martin Hilditch finds out why, and what she thinks can be done. Photography by Julian Anderson

Polly Neate is an interviewer’s dream. “I’m the world’s least discreet person,” Shelter’s chief executive tells Inside Housing. “I have never met anyone worse than me.” As a former journalist herself – Ms Neate edited Community Care magazine from 1999 to 2005 – she presumably knows this is music to our ears. Discreet or not, Ms Neate definitely isn’t dull.

A born campaigner, her description of her approach to journalism as “I wanted to change things” probably sums her up more generally. She speaks with urgency and enthusiasm – giving the impression there is no time to be lost.

“I’m the world’s least discreet person.”

If, as some have privately argued, Shelter had become something of a sleeping giant in recent years, Ms Neate seems to be the ideal person to wake it up. Certainly, when it comes to the world of housing, and social housing in particular, she thinks there is immediate action needed.

Ten months into Ms Neate’s stint at Shelter, Inside Housing caught up with her at the charity’s London headquarters to find out how she’s looking to shake things up – and, if possible, the early results of the ‘Big Conversation’, a national consultation about social housing, which she initiated shortly after joining.

We meet just days after Doreen Lawrence, whose son Stephen Lawrence was murdered in a racist attack in 1993, spoke out in an interview about the Grenfell Tower tragedy.

She talked about a wider “indifference which too often sees dismissive landlords protected by a system that allows them to ignore social tenants’ fears and concerns”. Baroness Lawrence is one of a panel of 16 commissioners leading the aforementioned Big Conversation for Shelter.

Based on her experience of the sector so far, does Ms Neate agree with Baroness Lawrence’s diagnosis?

“Yes, I do,” she says without a pause, adding that she thinks that by using the phrase “institutional indifference” Baroness Lawrence had made a “useful comparison” with the Macpherson inquiry following her son’s murder that concluded the police were institutionally racist.

“We need to understand that the marginalisation and stigmatising of a whole section of society has become institutionalised in our housing system.”

“We need to understand that the marginalisation and stigmatising of a whole section of society has become institutionalised in our housing system,” Ms Neate states. “To give you an example of that, which actually is one of the things that really did shock me when I got to Shelter, is just the way that people are often treated when they present as homeless to the local authority.”

This can be “frightening”, she says. “Not only in terms of the fact that they don’t get what they need, but it is also the manner in which they are treated. That is about institutionalised discounting of a whole group of people.”

“[Grenfell] affected everything about how I approached the job.”

Baroness Lawrence’s comments, of course, were prompted by the Grenfell Tower fire, which killed 72 people. It is a tragedy that took place just before Ms Neate started at Shelter and she says it “affected everything about how I approached the job”.

“If it doesn’t end up that Grenfell made it impossible to ignore the level of social injustice that is perpetrated through the housing system then we will have failed in our job at Shelter,” she states. “It has to do that.”

Shelter’s Big Conversation about social housing was set up with the tragedy very much in mind. It has also commissioned research agency Britain Thinks to carry out in-depth research with current and potential social tenants to get their thoughts on “how to make social housing fit for the future”.

The conversation has certainly caught people’s imagination, with more than 30,000 responses, according to Ms Neate. Half of these come from social housing tenants. This work is still being pulled together and analysed. “I’m under strict instructions that I’m not allowed to say too much about this,” Ms Neate says, before immediately making her statement about being the world’s least discreet person. There are, therefore, a few headline snippets Inside Housing can pick up – and it’s sobering reading for the sector.

“Grenfell really showed us there was no relationship of trust between the people who lived there and their landlord, the council,” she says. “That had completely broken down.”

Shelter’s work suggests “that is mirrored elsewhere”, Ms Neate says. The research also reveals a

widespread feeling among social tenants that they have been marginalised and stigmatised.

Ms Neate takes pains to point out that she is not criticising frontline housing staff for the lack of trust. “I don’t think that’s what the issue is. It’s what I said before, which is the difficulty of having to ration a resource that people desperately, desperately need and having to do it when there aren’t enough of you to do the rationing properly.”

“If social housing was something we were all proud of as a society and valued, housing officers would be as beloved as nurses.”

In this respect housing and homelessness officers are very much like social workers, she suggests. This means they get into the job because of their values, but are then faced with a lack of resources, have to gatekeep access to services and intervene late in the day rather than helping to “stop things falling apart in the first place”, she says.

“If social housing was something we were all proud of as a society and valued, housing officers would be as beloved as nurses,” she says. “But they are not, are they? In fact, nobody even knows what they really do.”

She adds: “We have pride in our welfare state, apart from when it comes to housing.” The result is that people who need help from the system are left in a terrible situation, Ms Neate says. She became very aware of this in her previous job as chief executive of Women’s Aid.

“At Women’s Aid I met a lot of women who would rather risk their lives than make themselves and their children homeless,” she states. “And that is because when you make yourself homeless there is absolutely nothing there. You fall out of the bottom of society, really. That really shocked me when I first realised that. The welfare state that we all assume is there to pick us up isn’t in housing.”

“The welfare state that we all assume is there to pick us up isn’t in housing.”

While we have so far concentrated on the problems, Ms Neate is definitely focused on answers. She remembers saying in her interview for the job: “What if Shelter punched above its weight? How incredible could that be?”

Did she feel the charity had perhaps not been campaigning as loudly as it might?

“I would rather frame it in terms of the situation that we find ourselves in now, in relation to housing,” she states, picking her words carefully. “In my mind it does not lend itself to too much policy critiquing. It is not enough just to point out where things are going wrong. We need to be setting out an alternative vision.” Most importantly, there needs to be a new vision for social housing, she says.

Why does she think that? “Well, there isn’t one, is there? I think there are a lot of people arguing about how many units we need and what tweaks to the planning laws might allow them to be built… There are all these somewhat technical questions and I think we need to not get bogged down in them.”

When it comes to social housing, “if you want to make it happen, you can make it happen”.

“It is making people want to make it happen that I’m interested in – I don’t want to get involved in the technicalities.”

In terms of Shelter’s role in this, the Big Conversation will help set the agenda, along with the results of the charity’s biggest ever consultation with staff, to inform a new strategy that will come out later in the year.

“One of the big things they [staff] are saying is they want us to be more focused and stronger in advocating for the people we work with in our services,” she says.

“What I want to be doing is looking at those individuals we work with and putting the journey they want to be on at the centre of everything we do,” she adds. “How do they want their life to be and how can we change things so they can achieve that?”

“If you are Shelter and this sort of perfect storm erupts around you, you bloody well need to make something out of it."

This may well involve working more closely with people in local communities – and forming partnerships with smaller charities at a local level – but also campaigning nationally to “change society, which I think is what Shelter was founded to do”.

Ms Neate is certainly focused on making sure change happens. The scale of the housing crisis is such that it is high on the public’s list of concerns, she thinks. As a result, as Ms Neate says, Shelter’s campaigning could have a real impact – indeed this “is a responsibility”.

“If you are Shelter and this sort of perfect storm erupts around you, you bloody well need to make something out of it, otherwise you are failing in your responsibility.”

At a glance: Homelessness Reduction Act 2017

The Homelessness Reduction Act 2017 came into force in England on 3 April 2018.

The key measures:

- An extension of the period ‘threatened with homelessness’ from 28 to 56 days – this means a person is treated as being threatened with homelessness if it is likely they will become homeless within 56 days

- A duty to prevent homelessness for all eligible applicants threatened with homelessness, regardless of priority need

- A duty to relieve homelessness for all eligible homeless applicants, regardless of priority need

- A duty to refer – public services will need to notify a local authority if they come into contact with someone they think may be homeless or at risk of becoming homeless

- A duty for councils to provide advisory services on homelessness, preventing homelessness and people’s rights free of charge

- A duty to access all applicants' cases and agree a personalised plan

Cathy at 50 campaign

Our Cathy at 50 campaign calls on councils to explore Housing First as a default option for long-term rough sleepers and commission Housing First schemes, housing associations to identify additional stock for Housing First schemes and government to support five Housing First projects, collect evidence and distribute best practice.