You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Is it time for Passivhaus?

Passivhaus homes have been something of a non-starter since they burst onto the scene a decade ago. But are they finally about to go mainstream? Words and photography by Simon Brandon.

Continental Europe has often been way ahead of Britain. Roads, wine, garlic – we are slow adopters compared to our friends across the Channel.

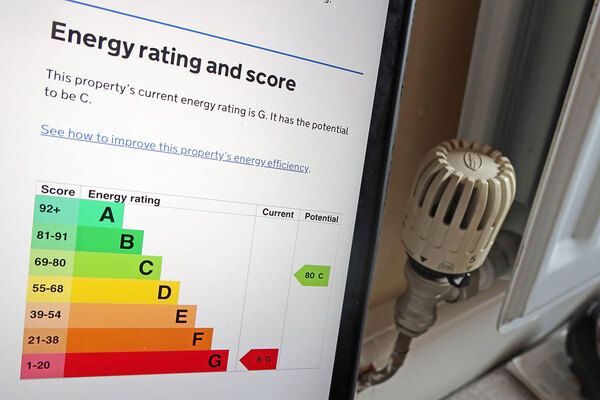

Energy-efficient housing is no different. In 2008, when the first Passivhaus-certified building was built in the UK (see box: What is Passivhaus?), there were already thousands across Europe. Since then, the growth of Passivhaus here has been slow, but momentum is building. According to the Passivhaus Trust, there were around 500 Passivhaus homes in the UK in total at the end of last year; the trust’s chief executive, Jon Bootland, expects that number to double this year alone.

There are other signs that Passivhaus might be poised for take-off. Last year, Hastoe Housing Association put three new Passivhaus-standard family homes up for sale in the village of Wimbish, north Essex. They were snapped up within months.

That could be significant, because while building to Passivhaus standards costs around 10-15% more, neither that cost nor the savings the energy efficiency will generate over the home’s lifetime are factored into valuers’ estimates.

“Even though the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors’ (RICS) guidance doesn’t have any mechanism to increase the value [on the basis of a home’s energy efficiency], our valuer priced the Passivhaus homes at the top end of a three-bedroom house in that area,” explains Ulrike Maccariello, development manager at Hastoe (pictured above). “We sold at that price. We didn’t have to drop it.”

The Wimbish homes are desirable for other reasons, too: they are in a rural exception site on the edge of a village, which is itself in a sought-after part of the country. Whether their energy efficiency was factored in by their buyers is hard to tell.

“If you’re a developer, then unless the user will pay more because it’s Passivhaus or very low energy then you’re investing time and money and not getting a return.”

Jon Bootland, chief executive, Passivhaus Trust

The question is whether buyers on the open market elsewhere are willing to pay that premium. If so, Passivhaus development could blossom. It’s a tantalising thought: the drastic reduction in energy usage offered by Passivhaus homes would, at scale, help tackle climate change and fuel poverty and would decrease the UK’s reliance on imported fossil fuels. Could the Wimbish homes be a harbinger of a growing demand?

Paving the way

Social landlords have been the trailblazers in building energy-efficient homes, but it hasn’t yet made sense for private developers. “If you’re a developer, then unless the user will pay more because it’s Passivhaus or very low energy then you’re investing time and money and not getting a return,” explains Mr Bootland.

So why have social landlords embraced these standards? For a start, there is clearly social value in building energy-efficient housing. For low-income families, saving hundreds of pounds a year on the cost of heating a family home is a huge boon (see box: Living in a Passivhaus). But there are also financial reasons behind social landlords’ enthusiasm for building this kind of home.

Two years ago, Hastoe reported a significant drop in rent arrears from tenants living in their Passivhaus homes three years after having moved in (Inside Housing, 13 February 2014). Sustainable Homes published a report in 2016 on the impact of energy-efficient housing on social landlords’ income. Using Energy Performance Certificate data from 25 housing providers with 500,000 homes between them, the report found “a strong correlation between lower rent arrears, lower void rates and more energy-efficient properties”.

And there is an assurance of quality, according to Bevan Jones, managing director of Sustainable Homes. “Passivhaus focuses on energy efficiency, but it also gets over those quality problems lots of social landlords suffer from their contractors,” he says. “You have to be good to build Passivhaus. It ticks several boxes for you as a landlord manager.”

It is becoming easier and cheaper to build Passivhaus in the UK, too. The market here has matured over the past few years, and its associated costs – for design, materials, construction and skills – are coming down as a result. The pieces are in place – or some of them, anyway. Changing the RICS guidelines to take energy efficiency into account when valuing properties would be another big help in selling these homes, Ms Maccariello believes. That conversation is under way – the Passivhaus Trust and Sustainable Homes say they have spoken to RICS and that things are moving in this direction.

“You have to be good to build Passivhaus. It ticks several boxes for you as a landlord manager.”

Bevan Jones, managing director, Sustainable Homes

According to Professor Sarah Sayce, a member of the RICS valuation board, much depends on mortgage lenders. “The mortgage market may well move,” she says. “Lenders are starting to look at your lifestyle and outgoings, so they may well want to know if it’s a house where you need to spend loads on the heating bills. At the moment it doesn’t affect [their calculations], but it probably will.”

But these are small steps – or little bricks in the wall, as Mr Bootman puts it. What could really boost Passivhaus adoption in the UK, he says, would be if near-zero energy building or zero carbon targets were to be adopted across the board. “A third or half of low-energy buildings could be Passivhaus; it’s a proven supply chain and proven performance,” he says.

And that might depend, once again, on the UK keeping up with Europe. A 2010 EU directive requires all new buildings to be near-zero energy by the end of 2020, by which time the UK will no longer be a member of the bloc. And so while the country waits to see what the Brexit negotiations may bring, it looks as though the affordable housing sector will be the UK’s Passivhaus champions for a while longer.

What is Passivhaus?

Passivhaus is a set of internationally recognised quality assurance standards for energy-efficient buildings. These standards specify stringent criteria around properties such as airtightness, thermal performance and energy usage.

While technology is used in Passivhaus buildings – principally in the form of heat recovery ventilation systems – the criteria measure the performance of the building’s fabric itself.

For example, a Passivhaus-certified building must achieve a maximum of 0.6 air changes per hour; that’s equivalent to a hole the size of a 5p piece in every five square metres of building envelope, according to the UK’s Passivhaus Trust.

By comparison, the airtightness of a new home mandated by UK building regulations is equivalent to five 20p pieces for every square metre of building envelope.

These buildings have to be insulated extremely well, too; the temperature of an interior window pane in a Passivhaus building cannot drop below 17 degrees celsius at any time of the year.

A Passivhaus building, then, is essentially an airtight and highly insulated box. Fresh, filtered air is pulled in from outside by mechanical ventilation systems that warm it using heat recovered from the stale air going the other way.

Living in a Passivhaus

You wouldn’t know to look at them, but the newest houses in the village of Wimbish, north Essex, are cutting-edge eco homes. They are large and boxy with red tiled roofs and red brick facades, broken up with square patches of wooden cladding.

The only external clue to their eco credentials is a pair of circular metal ventilation grilles, each about the size of a dinner plate, situated on the wall next to the front door. These are the vents for the house’s heat-exchanging ventilation system.

Nicola Martin, 32, lives here with her partner and four children. The first thing she noticed after moving into her new home, she says, was the absence of any draughts. “In my last house, it was horrendous,” she says. “There were gaps round the doors – it was always cold. We were always feeding the meter. Here, the heat stays in.”

There is a chill in the air outside today, but Ms Martin’s kitchen is warm.

She has just finished baking a cake and the residual heat from the cooling oven is keeping us toasty.

In this house, using an electrical appliance is all you need to warm things up.

“You use the house to your advantage,” says Ms Martin. “If I use the tumble dryer in the evening, I don’t need to turn the heating on… I’ve got three girls and they are always drying their hair. If you go into a room and they’ve used hairdryers, you can feel it, especially in winter. It warms up the house.”

She even credits the house’s air filtration system with helping her son’s asthma. “He had a chest infection every four months from when he was born until he was about three,” Ms Martin says. “He hasn’t used his inhalers since we moved into this house. Not at all.”