You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

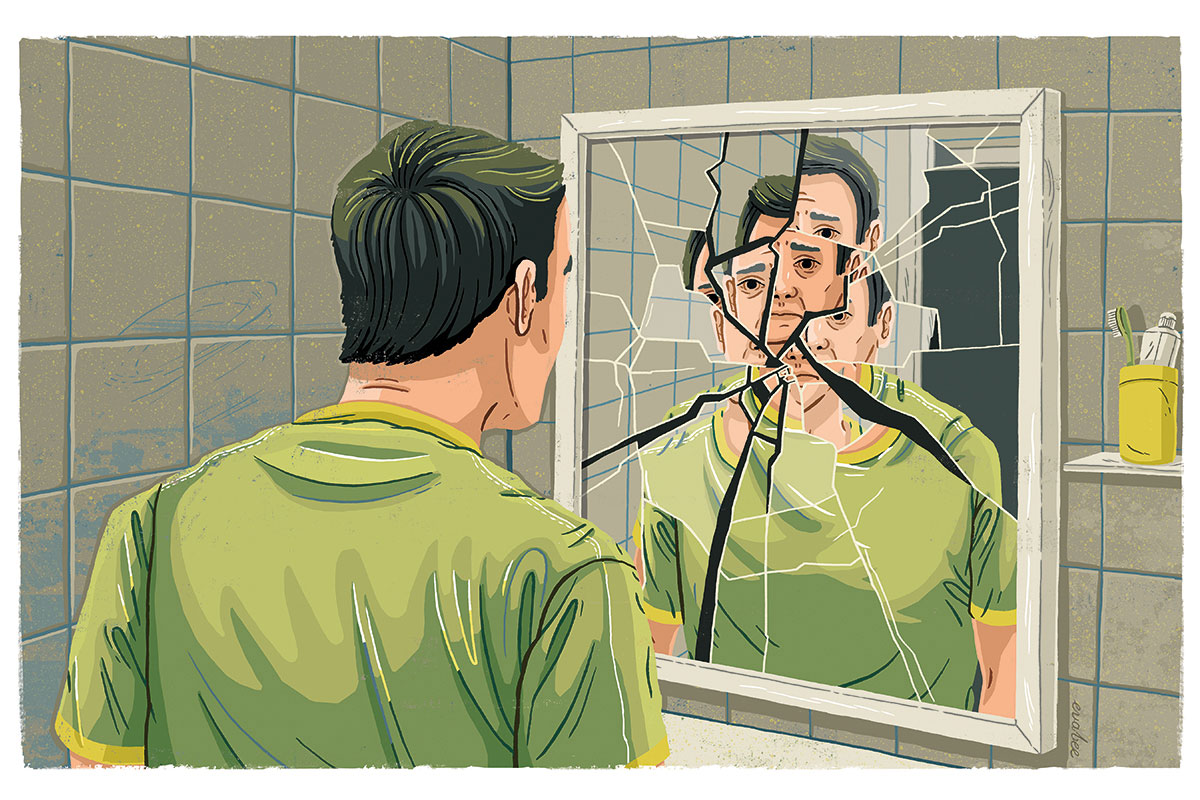

Picking up the pieces: suicide prevention

Poverty, isolation and unemployment are risk factors associated with suicide. Simon Brandon finds out how housing providers can support vulnerable residents. Illustration by Eva Bee

The number of people taking their own lives is on the increase in the UK. It now seems inarguable that austerity and welfare reform have played a part in that rise.

“There is a link between suicide rates and austerity – that has been clearly demonstrated,” says Siobhan O’Neill, professor of mental health sciences at Ulster University. “It’s associated with being on benefits, with sanctions – there are plenty of case studies where that has been the last straw.”

Research by the University of Portsmouth and Webster Vienna Private University, published in the journal Social Science & Medicine in 2015, found increased rates of suicide among men across Europe following the introduction of austerity measures in the wake of the 2009 recession. Poverty, social isolation and unemployment are all risk factors associated with suicide, according to the Mental Health Foundation.

Social landlords house some of the country’s poorest and most vulnerable citizens, so perhaps it isn’t surprising to hear that housing providers are reporting an increase in the number of their residents considering committing, or threatening to commit, suicide. But what is the scale of the issue, and what are housing providers doing to help prevent suicide among their tenants and support staff faced with vulnerable residents?

Recognising risk

A 2013 survey by the Northern Housing Consortium of 700 employees working at 10 landlords in the North of England found that, within a six-month period, 45% of housing staff had dealt with tenants threatening to kill themselves, while only 25% felt well-equipped to deal with this. Ninety per cent of respondents had found tenants in general to be in more financial difficulty than six months previously.

But the effects of austerity are being felt by the housing sector for other reasons, too. Cuts to local authority budgets have led to reductions in the number and capacity of mental health services.

“The squeeze on mental health services means people are not getting the support they need, and often the people who need those services are in social housing,” says Neil Gregory, learning and development officer at Mental Health Matters, a provider of mental health services and training based in the North East of England. “And it’s their housing providers that are having to pick up the pieces.”

Christine Clark, mental health trainer at Liverpool-based organisation In Equilibrium, has worked with 20 housing providers over the past two decades. She has heard the same from her housing clients. “As there are fewer and fewer services available, it is much easier to ring your housing provider to speak to another human being rather than to speak to mental health services or your GP,” she says. “[Housing providers] have suffered a little from being accessible and kind, and building relationships with people. It means people gravitate towards you more when they are in crisis.”

“The squeeze on mental health services means people are not getting the support they need.”

Ms Clark and Mr Gregory report increased levels of interest from the housing sector in the suicide prevention training they offer, which is based on the Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST) model – a course that trains participants to recognise when people are at risk and to support them into immediate safety.

The facts

- In 2015 there were 6,188 reported suicides in the UK, a slight increase on the previous year.

- The number of suicides in Wales and Northern Ireland rose; the number fell in England and also in Scotland, where the number has been falling since 2011.

- Female suicide rates are at their highest in the UK in a decade.

- The number of female suicides in the UK rose by 3.8% between 2014 and 2015. In Wales the rise was 61.8% and in Northern Ireland it was 18.5% – although these rises might be explained by inconsistencies in the recording process in both countries.

- Male suicide rates are three times higher than female suicide rates in the UK.

Source: Samaritans suicide statistics report 2017

If housing providers are being forced to take up some of the slack in mental health provision then they are, at least, well placed to take on that role. As Ms Clark notes, a member of staff repairing a boiler might have more contact with that tenant than anyone else. “Often they are in a home longer than a social worker,” she says. “These guys are sometimes the ones to highlight that someone is not alright.”

Stockport Homes, the arm’s-length management organisation (ALMO) for Stockport Council, offers all frontline staff access to an ASIST course, as well as mental health awareness training and a mental health champions programme, in which experienced staff members will help less experienced colleagues deal with suicide threats made by residents. The organisation has also put in place other means of support for at-risk tenants, including a website (stockportsuicideprevention.org.uk) co-designed by the 11,000-home ALMO, and free counselling.

“In 2016 Stockport Homes contracted [local counselling service] TLC: Talk, Listen, Change to provide free counselling for customers who would like to talk through issues they may be facing,” explains Joanne Claridge, rehousing services manager at Stockport Homes. “Unlike other counselling services within the area, there are no waiting lists and customers can be seen immediately. In its first year, 558 sessions were delivered.”

Previously, Stockport Homes referred tenants to other services but made the switch after staff identified that tenants were having to wait for appointments. These steps seem to be paying off: according to Ms Claridge, staff have reported that they feel the number of suicide threats reported to them has decreased over the past two to three years.

Shared learning

At Newcastle-based Home Group, Sally Parsons, client services director, says these issues are taken very seriously – not least because of the group’s strong connection with supported housing. The 55,000-home organisation runs its own one-day suicide awareness course for staff. The group had dropped the course for a while but it’s back on the agenda, Ms Parsons explains, because the association found the need and level of mental health issues among customers has increased.

“We want our colleagues to be aware and to be able to spot the warning signs, and to be able to support customers through their darkest hours,” she says. “It’s a combination of suicide prevention, doing our best to prevent clients from going down that road, but also the aftermath – what to do when people do commit suicide, and the impact that can have on our colleagues working on the frontline.”

Home Group’s business culture is fundamental to the success of this policy, Ms Parsons adds. “We learn lessons from every incident – we share that within teams, and then regionally, then upwards to the safeguarding panel. We have a really good information flow up through to the panel and the board, and then we share that out to the wider organisation. It’s not about blaming anyone, it’s about what we could have done differently or better.”

Providers can also take practical steps to remove the means by which a person might take their own life. Suicide can be an impulsive decision, Ms O’Neill says, and steps such as ensuring windows on higher floors don’t open wide, restricting access to rooftops and providing ligature knives – so staff can quickly cut free someone in the act of hanging themselves – might make the difference between a person acting on their intention in that moment or not.

In the absence, what basic steps should frontline housing workers take to respond to and help at-risk residents? Be direct, says Mr Gregory, and don’t be afraid to ask difficult questions. “That can be hard because people don’t want to talk about it, they don’t want to put ideas in someone’s head – but if someone is going down that path, you won’t do that,” he says. “Either they will say ‘oh no, I would never do that, I just feel terrible at the moment’, or you are giving that person permission to speak and say ‘yes, actually I have thought about taking a load of pills’.”

Ms Clark advises staff to “turn up their alertness” to be aware of warning signs and changes in residents’ behaviour that might belie the fact that they are struggling. “Do they look sad, or like they are not coping? Are they dressed [for the day]? What are they telling me? Some of it can be subtle. That is often the way people talk about not wanting to be here,” she says. “And pass that information on. It’s about asking questions and organising pathways to care for people who have fallen off the radar.”

But perhaps the most fundamental way housing providers can help tenants at risk of suicide is to do what every provider aims to do anyway: provide quality housing within inclusive communities.

“More important than all of that is providing people with housing that dignifies them, giving them a life worth living,” says Ms O’Neill. “You need to create an environment that is conducive to positive well-being. Feeling part of a bigger community is really important – that can stop people from acting on their suicidal thoughts. Creating communities is vital.”

View from the frontline

Jill Charnock, client service manager at Home Group, manages a 23-bed offender unit in central Lancashire for people at risk of offending, ex-offenders or people who have been released on bail. Suicide is a threat for two main reasons: people on remand possibly face a long prison sentence, and those who have been released from prison may have a “rose-tinted” vision of what life will be like.

Staff have an “amazing relationship” with clients and are good at spotting if something isn’t right, Ms Charnock says. “Maybe someone is giving money away or making plans – we are looking for those clues all the time.”

The team has saved lives as a result. They were recently called to a verbal argument between two clients. They stayed with the woman – who wanted out of the relationship – for an hour before supporting the man, who was very angry and upset.

“It’s all about knowing your clients, looking out for changes in their behaviour.”

“When he left the lounge, the staff just had an instinct that something wasn’t right,” says Ms Charnock.

“They followed him back to his room and he had slit his wrists quite deeply. They helped him to dress his wrists, sat and talked with him for an hour, talked things through, talked about healthy relationships – and he seemed to calm down. They made him a brew, and he refused any medical attention.

“Everything seemed all right. They observed him for a couple of hours – and then all of a sudden they saw him going back up the stairs. The staff told me they noticed something about the way he was walking, the way he was stopping on the stairs, so they nipped up just to check that he was OK, and found he had hung himself from his bathroom door.

“We cut him down with a ligature knife. We are very rehearsed in this procedure – we got another client to stay at the door, to make sure the paramedics went straight to his floor. A member of staff did CPR; the police and ambulance said that quick intervention had saved his life. Without that training and that awareness – without staff noticing changes in his behaviour – that might not have been the case.

“It’s all about knowing your clients, looking out for changes in their behaviour, mood or circumstances – things that could affect them – so we can help get them through the tough times.”