You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Planning White Paper: what is zonal planning and can it work?

In the last of our three in-depth pieces on the government’s proposed planning overhaul, Lucie Heath looks at plans for a zonal planning system in England and assesses the difficulties behind implementing it

“Why are we so slow at building homes by comparison with other European countries?” This question was posed by prime minister Boris Johnson in June as he launched his “build, build, build” plans to help the economy recover from the impact of coronavirus.

The prime minister’s answer was simple: it is our planning system. More specifically, he said, it is the delays in our planning system for things such as “newt counting” that hamper productivity.

Mr Johnson promised the government would tackle this problem by introducing “the most radical planning reforms since World War II”.

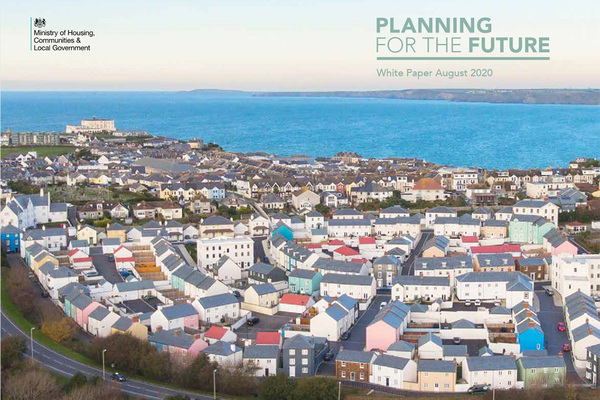

The details of this overhaul were unveiled last week in a white paper titled Planning for the Future.

At the heart of the government’s proposals lies the introduction of a ‘zonal’ planning system, that would see permission granted automatically on sites that have been earmarked for development.

Inside Housing takes a look at the proposals, asks how they compare to systems around the world and considers what impact they would have on housing delivery in England.

What is the government proposing?

The new system would see local authorities being asked to split all the land in their administrative area into three categories: growth, renewal and protection. Growth areas will be categorised as suitable for “substantial development”, with permission being granted automatically to developments that meet the requirements of a council’s local plan.

Renewal areas will include those that are suitable for some development, such as gentle densification, and protected areas will be places where development is restricted.

Local plans will be simplified, with the National Planning Policy Framework becoming the primary source of policies for development management. However, local authorities will be asked to develop design codes that “reflect local character and preferences about the form and appearance of development”.

How radical are these proposals?

The prime minister launched his “build, build, build” plans in June (picture: BBC)

From a UK perspective, introducing a zonal planning system would usher in a complete rethink of how land and development is governed.

The foundations of the English planning system – alongside the devolved systems of Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales – have largely remained the same since the Town and Country Planning Act 1947, which nationalised development rights by requiring individuals to gain planning permission before building.

However, the proposals appear far less radical from an international perspective. Zoning is an established concept that is used by many countries across the world.

A 2013 study by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation of 12 countries including England, the USA, Germany, France, and Australia, found that England was the only country with a planning system that wasn’t based on the concept of zoning.

The main difference between England’s system and the zonal systems used elsewhere is that the latter attempts to govern development through a predetermined set of rules. In comparison, the English system can be described as more discretionary, with decisions on planning generally being taken on a case-by-case basis.

However, zoning is not a one-size-fits-all system. The concept can be applied very differently depending on a country’s need or politics.

In Denmark, for example, the country has implemented a strict top-down zonal system, which sees the Ministry of Environment prepare national spatial policies. Meanwhile, the USA has no comprehensive state or federal planning system and rules are set at a city, township or county level.

The fact that England is one of the few countries without a zonal system provides a simple answer for driving construction for a government that is looking for a solution to the country’s complex housing crisis.

Yet to understand whether these reforms will deliver the kind of transformational change ministers hope for, a few key factors must be considered.

Speed and certainty

One of the biggest criticisms of England’s planning system compared to its international counterparts is that the system lacks certainty and requires developers to go through a long process without a reasonable guarantee of success.

This was one of the key points picked up in the right-wing thinktank Policy Exchange’s influential Rethinking the Planning System report, which is widely viewed as the precursor to the government’s white paper.

“Unlike most other planning systems in the world, there are no fixed rules that determine what must be done to gain the right to build. Instead, the right to build is conferred on a case-by-case basis according to sets of complex and often contradictory policies and case law,” the report’s authors wrote.

Many people agree that introducing more certainty to the English planning system could improve the way housing is delivered.

Richard Brown, deputy director at the Centre for London, says the new system would prove beneficial for smaller developers who “don’t have big pockets and don’t want to take on the risk of going through a two-year planning process to get permission”.

“I think one of the challenges in London, as everywhere, is the fairly small pool of developers who can actually afford to work within the system,” he adds.

However, whether a zonal system is faster is a point for debate. While applications may move more quickly through the system, the process of preparing the zoning plan is likely to be protracted, especially if local authorities are not properly resourced to meet these new duties.

“I can’t see how it will speed the system up,” says Rory Stracey, partner at Trowers & Hamlins, who suggests developers may end up drawing up design codes for overwhelmed councils to approve. “It’s either relying on developers holding the council’s hands because they’ve got a land interest or involves the council going: ‘Right, for every growth area in my administrative area I’m going to now produce a design code.’”

Added to that is the fact that the government plans to keep in place the current planning system as a back-up option for developers whose proposals don’t conform with local plans.

“I wouldn’t say it’s going to be less complex because at the end of the day, what they are suggesting is almost like a two-tier system,” Mr Stracey says.

Quality

Councils must agree a masterplan and design code for all sites in a growth area (picture: Getty)

The current government has earned a bad reputation for sacrificing quality in favour of deregulation, through the extension of highly controversial permitted development rights.

It is this reputation that has sparked a fierce backlash to the government’s proposals around zoning, with many commentators warning the reforms will clear the way for the “slums of the future”.

However, the government is adamant that design and quality will not be sacrificed via the implementation of a zonal planning system. This is because local authorities will be required to agree a masterplan and specific design code for all sites that are included in a growth area.

However, Dr Riette Oosthuizen, head of planning at HTA Design, warns that design codes are not a silver bullet.

“I’m worried that the government thinks that design codes translate into quality,” she says. “In London, we’ve seen permissions for the past 10 years working in the context of the London Plan and the housing SPG [supplementary planning guidance document], which is quite a detailed document around housing quality, but it hasn’t resulted in quality development. These things can be interpreted differently.”

Quality control over development will depend heavily on how detailed local authorities’ design codes are allowed to be and how empowered individual councils are to enforce them.

Democratic choices

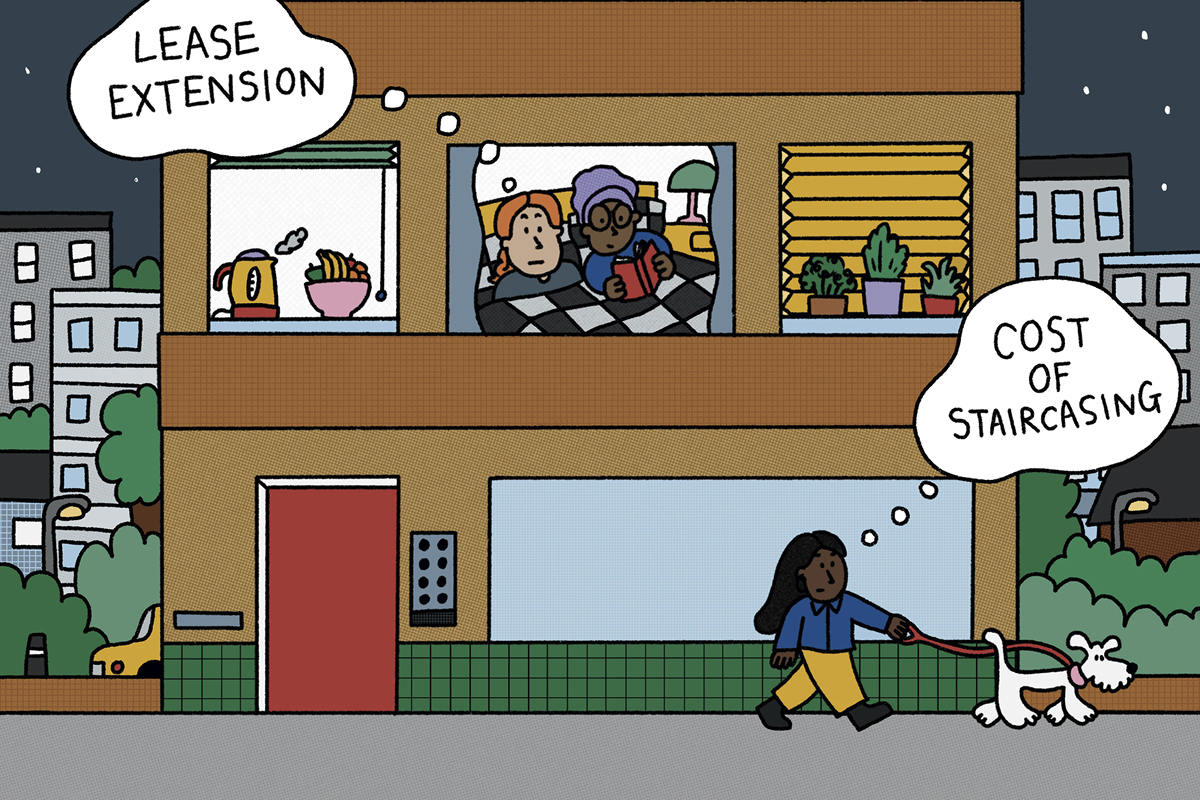

Another obvious criticism of the government’s proposals is that they erode the role of local democracy in the planning process.

Under the current system, planning applications go through a period of public scrutiny before they are approved and elected local leaders play an important role in making decisions. Under the new system, developments in growth areas will no longer be subject to this stage of the process and plans will instead be quickly signed off by a planning officer.

Yet the government insists that democracy will remain a key part of the planning process. Instead of residents engaging with individual planning applications, which the government argues gives disproportionate power to a small minority of voices, local people will be encouraged to participate more in the plan-making stage by giving their opinion on local plans and design codes as they are developed.

Mr Brown shares some sympathy with this idea. He says his experience with some community groups is that they feel frustrated under the current system when something is agreed in a local plan and then a planning application is passed that goes against what has been agreed. “Trying to make the actual plan-making process have more bite… feels to us to be positive,” he says.

Exactly how the government will encourage a larger mix of voices to engage with the plan-making process remains unclear. The white paper is also silent on what role will be played by metropolitan mayors, who currently play a key part in the planning system.

Like with quality, the role of local people in the new system will depend heavily on how local design codes are developed and utilised.

What’s missing?

There is one glaring fact that isn’t addressed in the government’s white paper. While the government has said that the current system is slow and cumbersome, it doesn’t get away from the fact that more than one million homes given planning permission by councils over the past decade are yet to be built.

While there may be a multitude of reasons for individual sites, a lot of this delay is due to developers’ commercial interests in controlling the speed of delivery.

The majority of developers are not incentivised to build when the market is weak, meaning planning applications are sat on for long periods of time.

The government simply promises to “explore further options to support faster build out” as proposals are developed.