You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The enemy within

Inside Housing has spent the last six years investigating life-threatening dangers on a number of housing estates following the death of a young woman from carbon monoxide poisoning. Today, following the conclusion of the UK’s largest ever gas safety prosecution, Martin Hilditch tells the full story of one of the construction industry’s darkest hours.

Source: Laura Dale / BNPS

The events that led to the UK’s biggest ever gas safety prosecution began when a single carbon monoxide detector was activated in a housing association flat in Poole, Dorset on a freezing cold winter’s day back in 2009.

Up to that point, the recently-completed 340-home Harbour Reach development had been seen as something of a triumph. Built between 2005 and 2007, the Daily Mail was moved to refer to it in 2008 as ‘the most luxurious’ social housing scheme in Britain, due to its prime waterfront location.

But on 27 January 2009, everything turned sour when a detector was switched on in flat 7 of a 16-home block called Shearwater House, owned by Raglan Housing Association, which was undertaking a programme to install detectors in all of its properties with gas heating.

‘It became clear very quickly that things were not right,’ Christine Haberfield, inspector of health and safety at the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), summarises.

How the media covered it at the time

A Shearwater House resident puts it even more succinctly. ‘He [the engineer] put the detector on and it just went off the scale,’ he says. The level of carbon monoxide recorded was so high that it represented an immediate threat to safety.

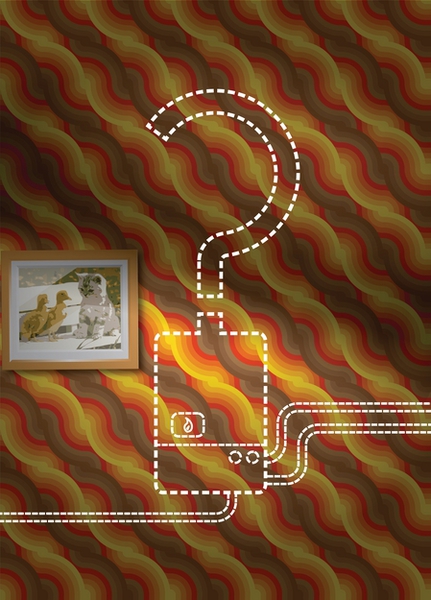

After the worrying level of carbon monoxide was found in flat 7, the HSE was contacted straight away and further work revealed problems with gas flue systems [the pipes that takes fumes away from boilers] in other properties. In some cases the faults discovered meant the boilers represented an ‘immediate danger’ to people’s safety.

Over the next couple of days, the supply to 149 homes was turned off because it was thought to be dangerous. After receiving an emergency report from a CORGI engineer, Southern Gas Networks then visited the site, built by developer Taylor Wimpey, and the decision was made to turn off gas to the entire Harbour Reach estate.

As the investigations proceeded, the scale of the problems uncovered was breathtaking.

Faults were discovered with the boiler flue systems in every single one of Raglan’s 60 homes at Harbour Reach. Over time, investigators found that 90% of the properties on the estate – 309 in total - contained some kind of flaw.

‘A significant proportion were immediately dangerous,’ Ms Haberfield states. ‘As a generality there was a lot wrong and it wasn’t just a little bit wrong. There were some cases where the flue terminated in the [internal] void and didn’t go outside [the property] at all. Some flues had actually started to come apart.’

So how did things go so wrong at Britain’s ‘most luxurious’ social housing scheme? And why did these initial findings turn into a sprawling five-year legal case that affected the lives of residents in two blocks of flats 90 miles away from Harbour Reach in Reading?

How the media covered it at the time

Inside Housing has carried out a detailed series of investigations over the last six years into problems relating to concealed flue systems across the UK. Today we reveal how the frightening discoveries in Harbour Reach led to the first successful prosecution relating to the installation of such systems. And following the conclusion of the legal case at the end of September, we can also tell the wider story of one of the UK construction industry’s darkest hours – and Harbour Reach’s position in it – in full for the first time.

As stated, the problems at Harbour Reach all concerned a common type of boiler system known as a concealed flue. This means that the pipes leading from the boiler are hidden from sight and do not exit the home directly through an external wall. When they were installed – mainly in the first decade of this century – it was almost impossible to check for faults in some cases. This was because for aesthetic reasons inspection panels weren’t inserted along the length of the walls and ceilings that the flues were placed behind.

Inside Housing has learnt that concerns about concealed flue systems had been raised nationally back in 2007. In April of that year the National House Building Council (NHBC) had issued a technical newsletter, which dealt with the issue of access to gas flues.

Its guidance stated that: ‘CORGI, and others within the industry, are concerned that with this type of flue, building designers may be tempted to route flues through the structure in such a way that they are not accessible for inspection and maintenance.’

Then, in June 2007, CORGI issued guidance that stressed ‘it is necessary to be able to visually inspect the flue system throughout its route, both prior to the initial commissioning of the appliance and subsequently during routine servicing.’

Nevertheless, the issue had a low profile outside of the gas fitting industry until the dangers were exposed in the most tragic way possible.

Fatal flaw

How the media covered it at the time

On 27 February 2008, 26-year-old dance teacher Elouise Littlewood died from carbon monoxide poisoning in the newly-built flat she part-owned with Notting Hill Housing at the Bedfont Lakes development built by Barratt West London (see box: The death of Elouise Littlewood). While there are no links between this and the legal case involving Harbour Reach, both developments contained concealed flue boiler systems, which had prevented engineers from seeing the full length of the pipe.

Barratt launched a massive inspection programme following Ms Littlewood’s death, visiting all of its developments started since April 2007 that had concealed flue systems – 1,986 homes in 65 housing schemes. In the majority of cases it didn’t find any problems but there were a few estates where it found ‘one or two problems’. These included two developments in Colchester – 179-home Balkerne Heights and 79-home Horizon – and its 50-home Brewery Wharf development in Leeds. Its checks uncovered two main issues – either brackets supporting flues were not put in place properly or inspection panels weren’t properly installed. It immediately remedied any issues it found

Persimmon was another developer that took action, looking at how many of its homes had been fitted with the system since 2007 and discovered that 1,096 could be affected. It wrote to all relevant homeowners and established that 384 homes ‘did not have access panels in accordance to safety requirements’.

Shortly after Ms Littlewood’s death the HSE issued a stark warning that 1,200 homes with concealed flue systems could be ‘immediately dangerous’ and a further 4,800 were potentially ‘at risk’. The figures were estimates based on the work carried out by Barratt and other developers following the tragedy.

This was certainly a risk to life at Harbour Reach. Richard Wisely, a Raglan tenant from Kittiwake House, said that after his flue was inspected it was found to have ‘sagged in the middle’. ‘It should have been suspended and fixed at certain points,’ he states. ‘It was very shoddily done. I can’t believe that a gas inspector would have passed something like that.’ Back in early 2009, Mr Wisely says his flat had one inspection hatch. Today there are three installed in his ceiling.

How the media covered it at the time

Ernie Hiddlestone, who lives in Shearwater House, says that on the day the first fault was found: ‘We were told it was a dangerous situation or it could be a dangerous situation.’ Today, he says he feels it was ‘lucky that there wasn’t a fatality’.

This view from the ground is shared by the HSE’s Ms Haberfield. ‘I think it is very, very fortunate that nobody was hurt,’ she says. ‘There were defects that were immediately dangerous that could have caused people to be ill or blown up actually. There were gas leaks.’

As the HSE began to undertake a painstaking examination of homes at Harbour Reach, the size of its case was about to increase. In 2009, Taylor Wimpey started to check another of its developments – two private blocks of flats, Malcolm and Jeffrey Place, in Caversham Road, Reading. The same firm, DSI Plumbing and Heating Limited, had been contracted to undertake the plumbing and heating work on both the Reading and Harbour Reach developments (it had then employed a number of other engineers to commission boilers at the sites). It quickly became apparent that there were similar problems with the Reading blocks – defects were discovered that affected about 75% of the homes. The HSE then extended its investigation to include the Reading site.

The scale of the problems and the number of systems that had to be checked meant the HSE was now faced with ‘the biggest gas investigation we have ever done’, involving checking 5,000 exhibits (such as bits of pipework) and working with at least 200 plumbers. One Harbour Reach resident, who wants to remain anonymous, states that in 2009 ‘you couldn’t move on this estate for gas fitters’. Even so, it took almost all of 2009 to fix all of the defects at Harbour Reach and install the appropriate number of inspection hatches in the homes.

Facing charges

How the media covered it at the time

In 2013, after years of on-site investigations, sifting through the evidence and conducting interviews, the HSE decided to prosecute DSI Plumbing and Heating, along with two individuals, Robert Percival, of Legion Road, Poole, and Andrew Church, of Ensign Drive, Gosport for breaching the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974. Mr Percival’s charge related to the commissioning of gas installations at one property in Harbour Reach. And Mr Church, who was in charge of heating and plumbing installation work at Caversham Road, for making false entries into documents.

The case of Mr Church gives some clues, perhaps, as to how things went so wrong at Caversham Road. The Crown Court at Bournemouth heard that in 2006 construction work on the Caversham Road development had been running behind schedule. Mr Church had written an email to DSI’s management in which he said he was working 16 to 20 hours a day and sleeping in his van some nights to try and get the work done. He suggested that the ‘timelines and targets’ that Taylor Wimpey wanted to meet were ‘too much’ and that ‘none of the scheduling for trades has been thought through at all’. He asked for help and said that he was ‘not Superman’. Doctors told him that he was suffering from exhaustion.

Technical guidance

Mr Church’s charge related to him signing documents stating that a number of boilers had been commissioned (installed and checked), which in fact had yet to be commissioned.

Andrew Church pled guilty and was given a two-year conditional discharge

September this year marked an historic moment as DSI Plumbing and Heating, of The Square, Fawley, was fined a total of £10,000 after pleading guilty to two breaches of the Health and Safety at Work Act. It was also ordered to pay £1,000 in costs.

Mr Percival pleaded guilty to a single breach of the same legislation for his commissioning of gas installations at one property in Harbour Reach and Mr Church for making false entries into documents relating to the Caversham Road site. They were both given a two-year conditional discharge and were each ordered to pay costs of £250.

There had never previously been a successful prosecution relating directly to problems with concealed flues. Indeed, the decision to bring charges was taken shortly after the failure of all prosecutions related to Ms Littlewood’s death and the Bedfont Lakes estate – a plumber was found not guilty of both manslaughter by gross negligence and causing grievous bodily harm and his employer was cleared of failing in its duty to protect non-employees from risk back in June 2012. Neither had any connections to the Harbour Reach case.

Robert Percival also pled guilty and received a two-year conditional discharge

A spokesperson for Taylor Wimpey emphasised that it was not involved in the legal action relating to Harbour Reach and Caversham Road and did not want to comment on the issues raised by Mr Church in his mitigation.

She states: ‘All gas flues that were installed by the subcontractors used at Harbour Reach have been inspected and we no longer use extended gas flues in any of our new build developments. In addition, Taylor Wimpey has written to all home owners on all of its developments with extended gas flues from 2000 and completed follow-up inspections where necessary.’

The developer did identify issues on two other estates – the 791-home Grand Union Village, which straddles the London boroughs of Ealing and Hillingdon, and a 182-home estate in Borehamwood [see box: Problems in Borehamwood]. In February 2012 it told residents of Grand Union Village that it was focusing attention on the estate’s Harborough and Brecon House ‘due to our inspections identifying significant issues relating to the gas flues within these blocks’. It had initially acted after ‘elevated levels of carbon monoxide’ were discovered at one apartment.

It’s important to emphasise that no developers have faced any charges as a result of problems with concealed flue systems.

A spokesperson for Raglan says that it had also checked other properties it owned with concealed flues, following the problems at Harbour Reach. It discovered no further faults although on two developments ‘it was necessary to install inspection hatches to allow a visual inspection of the flues as part of the annual servicing programme’.

As a direct result of the problems discovered, new technical guidance was developed and since January 2013 engineers carrying out annual checks have told householders that their boiler is ‘at risk’ if inspection hatches are not fitted – even if they have passed previous checks.

The whole story represents a cautionary tale for social landlords and developers alike. The scale of the problems with Harbour Reach were mind boggling, but it was far from unique.

Elouise Littlewood died as a direct result of the flaws with her boiler but in many ways it is a miracle that there haven’t been a number of other casualties. The residents of Harbour Reach were lucky – nothing more. Developers and landlords alike need to make sure that their residents are never again left relying on similar good fortune.

The death of Elouise Littlewood

In winter 2008, Alan and Sally-Anne Littlewood’s world collapsed around them.

At 3pm on 27 February, Mrs Littlewood received a call to say that her daughter Elouise (pictured right) had failed to turn up for work.

The absence, without a word of explanation, was completely out of character for the 26-year-old, who was employed by Hawk Training as a tutor and assessor for children’s care, learning and development.

Her mother was so worried that she left work and dashed to Elouise’s flat in Wooldridge Close on the nearby Bedfont Lakes estate, near Hounslow. She became even more concerned when she spotted her daughter’s car outside the flat but got no answer after knocking on the door.

By now she had called her husband, who left his workplace and arrived at the flat soon after. They were then joined by the brother of Elouise’s lodger, Simon Kilby, who said Simon had not been seen by his colleagues all day - again without calling in sick. The families decided to phone the police.

When officers arrived the families gave them permission to kick open the front door. ‘They realised straight away that the chain and locks were on from the inside,’ Mr Littlewood says. ‘That’s when they sent me away.’

Mrs Littlewood simply states: ‘That was the beginning of the nightmare.’

Read the interview in full here.

Source: Rogan Macdonald Alan and Sally-Anne Littlewood

Problems in Borehamwood

Kellie Simpson and her family received a terrible shock in the middle of July 2012.

Gas engineers told her that the boiler system in her flat, in Borehamwood, Hertfordshire, was potentially unsafe and would have to be shut down immediately. Left without access to hot water she was immediately re-housed, along with her partner and seven-year-old daughter, in a nearby hotel.

Across the estate, other families were packing their bags and leaving their homes after receiving the same worrying news. Overnight many of the properties, which were only built five years previously, were emptied as boilers were shut down.

‘The engineers said “we are really, really sorry but it is the way it [the boiler system] has been put in”,’ Ms Simpson recalls. ‘They said it would have to be condemned.’

Ms Simpson, who is a private tenant, says she was told that while there had not been a carbon monoxide leak in her home, the engineers discovered that the flue pipes were not connected as securely as they should have been. This presented a risk to the family if left unchanged.

It was almost two months before Ms Simpson and her family returned home, due to the time taken to get replacement parts. ‘I feel like I have lost seven weeks of my life,’ she says when Inside Housing met her, still unpacking bags and cleaning the flat, the day after she has moved back in. She says she was frantic with worry when she discovered there might be a problem with the gas system in the home. The concealed pipes ran through the ceiling in her daughter’s bedroom.

Source: Rogan Macdonald