The new social housing: data shows scale of infant children in temporary accommodation

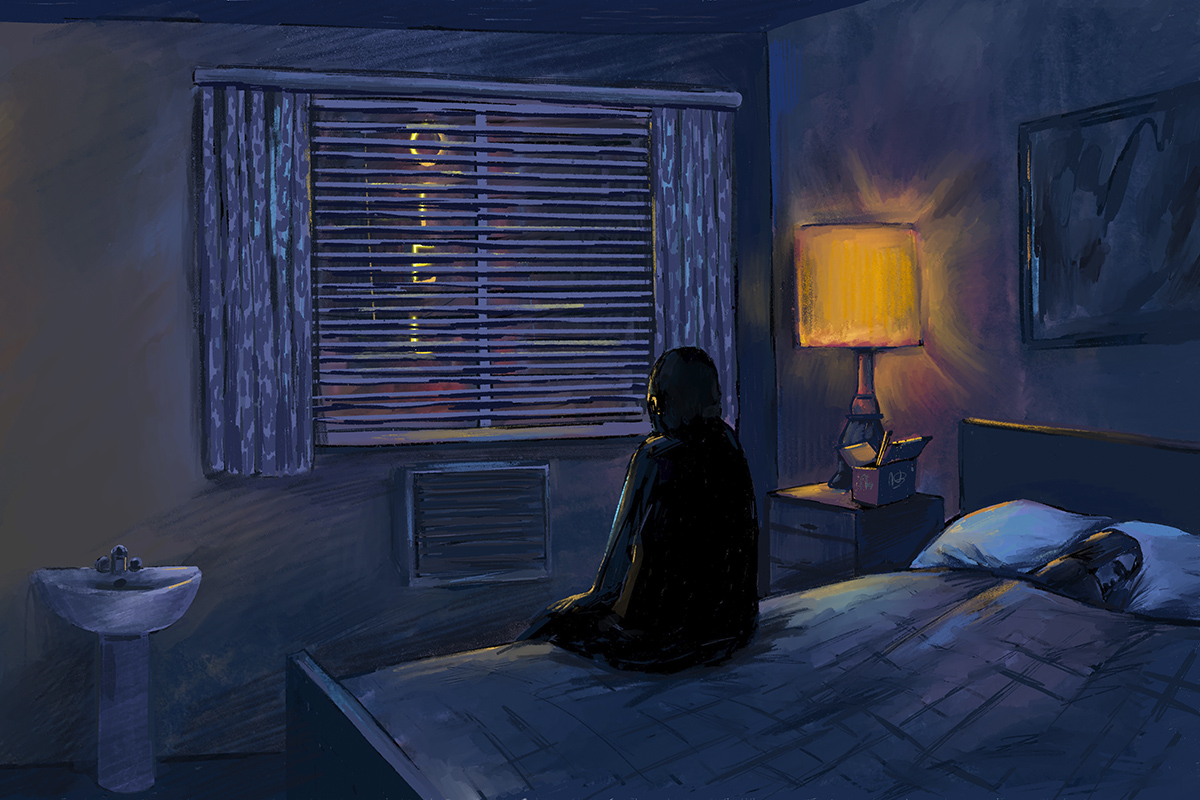

New data gathered by Inside Housing shows a city’s-worth of under fives are homeless and living in temporary accommodation. Peter Apps reports. Illustration by Alexandra Dzhiganskaya

“All of the information about how to mother just doesn’t work,” says Jane Williams, founder of charity The Magpie Project, which works with the ever-growing population of homeless mothers in Newham, east London.

“Even if you think about really basic things, like a bedtime routine, that’s impossible. Weaning, that’s impossible. All of these things that have been passed down generations about how to mother are made impossible by this housing situation.

“It’s the definition of torture to have that taken away from you. Everything in your body is screaming at you to make your surroundings safe for your child and you just can’t.”

It is often said that Britain has a housing crisis. But perhaps the sharpest end of this crisis is happening largely hidden from view and is far too rarely talked about by policymakers.

In 2010, when the Conservatives first came to power, there were 37,940 families with children in temporary accommodation. Now, 12 years later, there are 59,500 – a staggering 56.8% rise.

New data gathered by Inside Housing sheds new light on a particularly upsetting facet of this: the number of infant children without a home and living every night in temporary housing – which in real terms usually means a hotel room often without cooking facilities; a studio flat in a converted office on the edge of town; or a single room in the absolute bottom end of the private rented sector.

Children under five

We asked councils to provide data on the number of families in temporary accommodation with children under five years old. Only 22 were able to provide figures (they are not obliged to record them, but some do for monitoring purposes).

However, among the 22 were several large London boroughs, which meant the figures covered more than 20% of England’s temporary accommodation population.

The results show that 38.6% of households with children in temporary accommodation within this sample had a child under five, with an average of 1.16 children under five in each of these households.

“Everything in your body is screaming at you to make your surroundings safe for your child and you just can’t”

If these figures are representative, they would indicate that 22,976 households with children under five were in temporary accommodation at the time of the most recent snapshot figure, with 26,641 children under five in total. To put this in context, it is roughly equivalent to the number of under-fives in one of England’s larger cities, such as Liverpool, Manchester or Bristol. Or, put another way, it is nearly 900 primary school classes of homeless under-fives.

Why has this happened? Why does it matter? And what can be done about it?

Ms Williams’ Magpie Project operates in Newham – the eye of the storm when it comes to homelessness and temporary accommodation. At the last snapshot, in June 2022, the borough had 4,034 families in temporary accommodation, including 8,363 children – by some distance the most severe crisis in the country.

The figures provided to Inside Housing show that 1,434 of these families had a child under five, with 1,773 under-fives in total in the borough.

The picture Ms Williams describes of life for these families is bleak. “The mothers that we work with are brilliant, brilliant mothers, but they are doing it with nothing,” she says. “There are so many families in hotels with no cooking facilities at all and that just means you can’t nourish your child. You have got a kettle and a sink and that’s it. If your child wants hot milk to go to sleep at night, you have got no fridge.”

This means the mothers are reliant on takeaway food to feed their children: even food banks are of little use with no means to cook the food.

Ms Williams describes one mother who is “a wonderful cook”. “She can cook nutritious, culturally appropriate food for her children,” she says. “But she has to buy them fried chicken in a box, because she is being given no other option. If she was at least in a house with cooking facilities, we could get her to a food bank and she could provide for her children.”

Living in one room, which is often not child-proofed, has consequences for child development.

“There is no room to play or crawl on the floor,” explains Ms Williams. “A lot of the children are strapped into high chairs or buggies for most of the day.”

“We are seeing a lot of flat heads from children lying all day in one position. We are seeing poor muscle tone, because they are lying in buggies when they should be rolling around on the floor,” she says.

“We are seeing a lot of flat heads from children lying all day in one position. We are seeing poor muscle tone, because they are lying in buggies when they should be rolling around on the floor”

With the country recently shocked by the tragic death of two-year-old Awaab Ishak in Rochdale, who died after being exposed to damp and mould in his housing association home, the housing conditions in these properties are also of major concern.

“These homes are not fit for human habitation. They are full of mould and we see children hospitalised because of mould and damp. There are infestations of mice, bed bugs. Those things are so prevalent, they are everywhere,” she says.

Then there is the cognitive development side. “We see really low engagement, almost like frozen babies who don’t engage and don’t play. What’s really frightening about that is they have really high cortisol levels, so they are really stressed, but they are not crying and not asking for help,” she says.

“We know that the first two years set up a child’s brain chemistry for the rest of their life. So this is really a life sentence. It’s not just about under-fives, it’s about future adults. We are in danger of breaking them before they get built.”

The pressure for mothers is also often close to unbearable: a horrible mix of stress, boredom and isolation, with intense financial pressure and insecurity, combined with a placement in a property that has likely moved them away from any social support networks which might have helped to sustain them.

In numbers: children in temporary accommodation

26,641

Estimated number of under-fives in temporary accommodation, according to Inside Housing research

56.8%

Rise in families with children in temporary accommodation since 2010

120,710

Children in total in temporary accommodation at the last snapshot figure in June

£1.6bn

Annual spend by local authorities on temporary accommodation provision

Source: Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, Shelter and Inside Housing research

“For families with under-fives, it’s really hard for the parents,” says Deborah Garvie, policy manager at Shelter. “Once they’ve put their kids down at seven in the evening there is nowhere for them to go. Some of them just have to sit there with the lights off all evening.”

“A lot of our mums go to the doctors and say they can’t sleep,” says Ms Williams. “And either the doctors say there’s nothing we can do about it, what you need is a house, or they say here are some sleeping tablets.

“But it’s not a mental health issue not being able to bear what is unbearable. That’s a proportionate response to what’s going on, but given that there’s no way out, they are being medicalised with anti-depressants and sleeping pills.”

The reasons we have reached this position are frustratingly simple. There is a chronic lack of social rented housing, which has not been built in large volumes at all this decade for the first time since World War II, at the same time as tens of thousands of existing properties have either been demolished or sold off.

“A lot of this comes down to the massive shortage in housing supply, due to not building enough truly affordable housing. We have seen the number of households who can move into social housing decline massively. And that’s led to a huge increase in those stuck in temporary accommodation for a huge length of time,” says Ruth Jacob, senior policy officer at homelessness charity Crisis.

Soaring rents

At the same time, the benefits system has been choked off. Local Housing Allowance (LHA) (the amount that can be claimed by a household in the private rented sector) was capped at a maximum of the 30th percentile of local rents and then frozen, which means there are swathes of the country where there is not a single home available for a family who cannot afford the market rates. As rents soar, this problem is becoming more acute.

“What we’re hearing is that councils are finding it impossible to find move-on accommodation,” says Ms Jacob. “There has been a huge drop-off in the affordability of the private rented sector. The LHA rate that people can get has remained frozen but rents have increased massively.”

Short-term lets like Airbnb have made this problem worse, cannibalising an already overheated market.

“Basically, temporary accommodation is the new social housing. It’s where you end up if you can’t afford the market and the state accommodates you”

“We have tourists sleeping in homes built for families and families sleeping in hotels built for tourists,” says Ms Williams.

“Basically, temporary accommodation is the new social housing. It’s where you end up if you can’t afford the market and the state accommodates you. That used to be social housing, but now it’s temporary accommodation,” says Ms Garvie.

The answers are as simple as the causes of the problem. We need more social housing and a benefits system that allows people to access housing and sustain their tenancies.

If the government is loathe to spend the money on this, it should consider the costs of temporary accommodation – where local authorities stump up nightly bills, transferring enormous state wealth into the hands of some of the most exploitative landlords in the country. Recent research by Shelter showed that the annual bill was £1.6bn.

“This is the crazy economics of temporary housing,” says Ms Garvie. “It has created a crisis-driven market. Local authorities have families with suitcases who they need to find housing for and they are doing their best, but this really is an impossible situation for them to solve.”

It is important, though, that if this crisis is tackled, it is tackled in the right way. Marc Francis, an advisor at Westminster-based charity Z2K, points out that a straightforward target to reduce the number of families in temporary accommodation could have the wrong impact.

Under the Localism Act, councils have the power to ‘discharge’ their duty to a family by offering them private rented accommodation, sometimes many miles away from where they live and inappropriate for their needs. If they refuse it, they risk losing access to any support. “We see that sword hanging over families a lot,” he says. “A straightforward pressure to reduce numbers isn’t always beneficial to the households.”

Nonetheless, it is plain that change is overdue. “How is this not seen as a disaster? If a river broke its banks and made 30 people homeless, it would be seen as a disaster. But that is exactly what is happening every week in this borough because of the housing market,” says Ms Williams.

A disaster feels like the right word. And this – like too many of those we face currently – is a man-made one.

Sign up for our homelessness bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters