You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

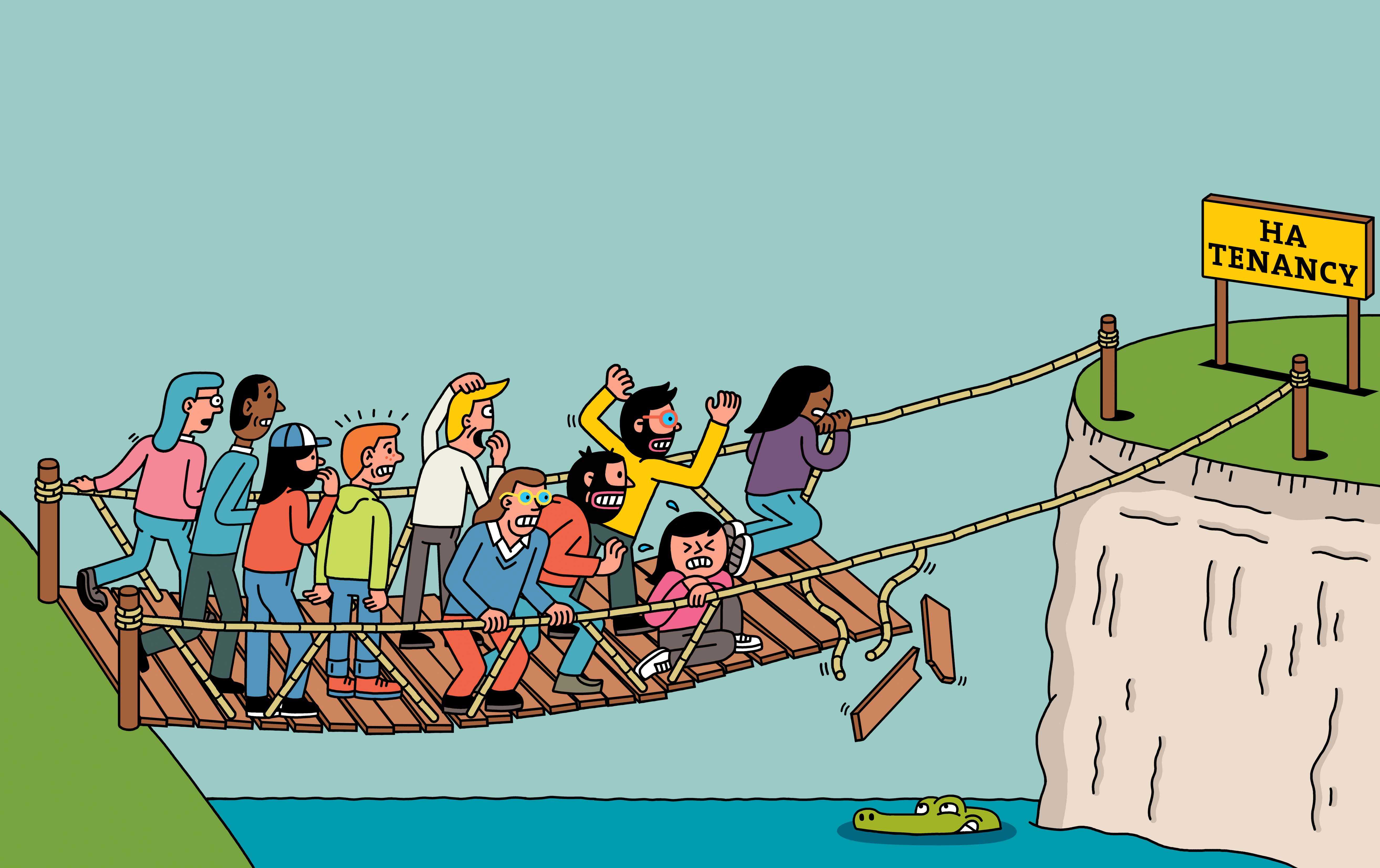

Under 35, on housing benefit, and impossible to house?

The ‘Local Housing Allowance cap’ is already narrowing the housing options for under-35s, Inside Housing reveals, with many housing associations planning to tighten allocation rules. Jess McCabe reports

But for prospective social housing tenants under the age of 35, 1 April marked a shift of great significance.

It heralded the start of a policy that Inside Housing has discovered is already fundamentally changing whether such ‘younger’ people will be able to rent a flat or house from their council or housing association.

That policy is the application of the ‘Local Housing Allowance (LHA) cap’ to social tenancies, which among other things severely restricts the amount of housing benefit that can be claimed by general needs tenants under 35, without children. Most will only be eligible for the ‘shared accommodation rate’ – based on the cost of renting a room in a shared house or flat. Although the cut to benefits only starts on 1 April 2018, it will apply to any tenancies signed from 1 April this year.

A Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) spokesperson noted that local authorities can use Discretionary Housing Payments to help tenants “transition to our reforms”, and said: “These changes are about restoring fairness to the system and ensuring that those on benefits face the same choices as everyone else. The reality is, nothing will change until April 2018, and existing tenants will be unaffected.”

But tenants picking up the keys to their new homes today will be affected if they are still relying on housing benefit to pay the rent in 2018, and are under 35 at that time. This also means social landlords are already making tricky decisions about whether they can rent to tenants they think will be affected – if it is at all unclear whether they will be able to afford the rent.

So Inside Housing sent a survey to the 180 biggest housing associations asking detailed questions about how housing associations are changing their allocation policies. Forty-seven responded, giving us a glimpse into how decisions on “how to get a housing association house” are changing on the ground.

Only 11% of them plan to make no changes to how they treat under-35s in their allocations policy, compared to 13% who have already made changes and 60% who plan to change their allocations in future.

“It’s likely a lot of the under-35s nominated to us will not be able to afford the property,” one housing association predicted.

Some of the changes being made will make it even harder for younger people to get tenancies from a housing association. Among those reported to Inside Housing are:

· Younger tenants to be given assured shorthold tenancies, or two-year tenancies, rather than more secure tenancy agreements.

· Blocking under-35s from renting in certain blocks of flats or certain buildings.

· Blocking under-35s from renting new build homes, as these will be rented under affordable rents set at up to 80% of market level, leaving an even larger gap between housing benefit entitlement and rent.

· Only accepting the youngest tenants, under the age of 21, if the council agrees it will pay their full rent.

· Additional affordability assessments.

Rather than restricting access to housing, a number of landlords are reducing rents for younger tenants with no children.

For example, Amicus Horizon plans for its new tenants under 35, without children, to be allocated social rent housing, rather than affordable rent.

This will still leave a shortfall – but not as great. “The shared accommodation rate of LHA is effectively half the one-bedroom equivalent, leaving most residents facing a weekly shortfall of £10 to £15 to make up through their own means,” explains Paul Hackett, chief executive of the 28,000-home landlord. “We’ll raise awareness before we let homes and offer help and advice through our tenancy sustainment and financial inclusion teams,” he adds.

“Our biggest concern is what will happen in two years when these tenants can no longer pay their rent – it’s likely they will be evicted and be seen as intentionally homeless.” Quote from anonymous housing association source

Housing associations are aware of the impacts of these changes on their younger tenants, and fear a cycle of homelessness is coming in the future. As one said, “Our biggest concern is what will happen in two years when these tenants can no longer pay their rent – it’s likely they will be evicted and be seen as intentionally homeless.”

Centrepoint, a London homelessness charity with 1,100 supported accommodation spaces, is at the sharp end, as its residents are under 24. Going back to the family home is not a solution for many of its young people, and the charity already struggles to help residents find suitable housing when they are ready to ‘move on’.

The charity worries it will face extra demand from young people made homeless because they are unable to afford their social or affordable rent – and a ‘bed-blocking’ scenario where it is impossible for its existing residents to leave.

Paul Noblet, head of public affairs at Centrepoint, says: “It’s really difficult to know where young people will go, unless there are thousands of thousands of homes built, or there are sufficient jobs that are paying sufficient salaries.”

The LHA cap and under-35s

The Local Housing Allowance limits the amount of housing benefit which tenants in the private sector can claim to help pay their rent.

But in November last year, George Osborne announced that the cap would be extended – and the same formula used to calculate entitlement to housing benefit for ‘social sector’ tenants as well, if they signed their tenancy agreement from 1 April this year.

From 1 April 2018, tenants under 35 with no children will only be eligible for the ‘shared accommodation rate’ set under the LHA, area-by-area. This limits most tenants under 35, if they don’t have children, to enough housing benefit to cover a room in a shared house. The rate is meant to be set at the lowest third of properties on the local rental market. This would not be enough to cover social or affordable rent for a council or housing association home.

There are a number of exemptions to the shared accommodation rate in the private sector, but the government has not yet said if the same rules will apply to social sector homes.

How many will be affected?

We don’t know how many tenants will be put on the shared accommodation rate, partly because the exact exclusions haven’t yet been announced and additionally the government has not yet published an impact assessment. In the absence of official calculations, some light is shed by examining the Department for Communities and Local Government’s CORE data on new lettings.

First consider age – the two age cohorts most likely to be allocated a new tenancy are those aged 25-31 (25%) and those aged 18-24 (21%). That means at least 46% of new tenants are definitely in the age bracket for the shared accommodation rate, although we don’t know how many have children or would be otherwise exempt. The next most significant age group is 31 to 38-year-olds (19%), an unknown number of which will be affected.

It is a good bet that many of these new tenants will rely on housing benefit, as only a quarter of all new tenants receive no benefits at all.

Understanding the rules

Only 66% of housing associations told us they are clear on the rules for the LHA cap on under-35s, even though tenants picking up the keys to their housing association flat or house today could be affected.

Partly this is because housing associations are still not sure about which tenants will be exempt. It’s already clear that under-35s with children will be able to get more than the shared room rate of housing benefit. Assuming that the rules match private sector housing benefit, people who have been in homelessness accommodation for six months should also be exempt – if they are between 25 and 35.

But housing managers told Inside Housing that the specifics of how this will work are not clear. “We are as informed as we can be at this time,” one said.

“We understand the rules that apply in the private rented sector – and that ministers intend to extend something similar in the social rented sector – but we will be lobbying for broader exemptions,” another association said – for example, it will be pleading the case of young, vulnerable tenants moving out of supported housing and into a general needs tenancy.

“We do not feel all the information from the DWP has been made clear. At landlord forums we have attended there has been some confusion across the sector,” was another comment.

Assessing tenants

Housing associations are already preparing for the shared accommodation rate – with 89% having analysed the benefit reductions that affected residents will face.

Only three of the 47 housing associations expect that local authorities will signal which of their new tenants will be affected by the change, with nearly half assuming that they will need to carry out checks themselves during the allocation process. Another 45% said they don’t know, expect to split the responsibility with local authorities, or expect different councils from which they take nominations to adopt different approaches.

Will housing associations set up shared housing?

If you are under 35, single and with no children – yet reliant on housing benefit – government policy is pushing you one way: a room in a shared house or flat.

But such houses are typically rented out by private sector landlords. Social landlords have barely any involvement.

Could that change in the future, as landlords perceive that most of their housing will be impossible for many under-35s to access?

The results of our survey suggest the answer is yes – with some qualifications.

Just under a third of housing associations are considering the development of shared housing for under-35s, in direct response to the LHA cap.

Still, there are reasons why housing associations are not already active shared housing landlords, with a perception that these tenancies are difficult to manage high up the list. In the private sector, tenants can find friends and acquaintances to move into any vacant rooms. But housing associations are tied to systems of allocating homes according to priority need, which makes such arrangements more difficult.

Grand Union Housing Group is typical of the 36% not considering this approach. “Shared housing is fraught with problems and there are very few (if any) examples of it working well,” the 11,000-home association said in response to our survey.

Another association said: “We have considered it but shared tenancies are very problematic to manage and are therefore unlikely to be introduced.”

Still, other associations are looking at more indirect ways to get involved in this part of the market. One in the South East told us it may set up a ‘matching’ service to help younger people find rooms in shared houses.

Local authority angst

The relationship between housing associations and local authorities is already under strain, primarily because of the Right to Buy extension, to be paid for by forcing local authorities to sell their own high-value stock.

But Inside Housing’s survey reveals that the LHA cap risks putting the two halves of the social housing sector further at odds. The reason? Housing associations may start turning down under-35s who are referred from council waiting lists, if they are entitled only to the shared room rate, on the basis they won’t be able to afford the rent. But local authorities will still have a statutory duty to house young people without children in this age bracket.

Some associations expect local authorities to be sympathetic. “There is a shared understanding that tenancies have to be sustainable and so affordability has to be considered,” one pointed out. Another hopes that local authorities could help to fund rents for affected young people.

But many associations already anticipate this will cause friction. “They would see it as a failure to meet our duties in addressing housing need,” one told Inside Housing. Another said its local authority would be “deeply unhappy. Although we’re entitled to do so it could place serious strains on our relationships”.

“We are likely to be challenged as this approach will breach most nomination agreements,” another said.

But housing associations worry that if they accept tenants who cannot pay their rent, without guarantees from local authorities, they could later be considered intentionally homeless if evicted due to arrears.