You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Why child abuse is a housing issue

Victims of child abuse are more likely to grow up into adults with housing problems. So should the housing sector be stepping up its response? Jess McCabe reports

Video:

features code

Behind the front door of an ordinary Victorian terraced house in Nottingham is an extraordinary project. In fact, it claims it be the first of its kind in the country - a hostel for male survivors of childhood abuse.

Nigel O’Mara, who opened the hostel in September, points out the walls he’s put up himself. In each of the bedrooms is a painting by a survivor of sexual abuse. “It’s not lavish, as you can see, it’s just a basic house,” says Mr O’Mara. “But within the home, everybody knows that they’re safe to talk.”

Survivor-led

The East Midlands Survivors Hostel is a small organisation - with only six bedrooms to rent. Yet survivors’ groups argue the broader housing sector should be waking up to the impact of child abuse on tenants and homeless clients. They say that childhood trauma is the underlying reason why many people end up homeless or struggle to maintain tenancies - and the sector should be doing much more to ensure need is met.

Video:

Ad slot

Mr O’Mara is himself a survivor of abuse. He straightforwardly explains, “I was brought up in care, and when I left the care system I spent quite a lot of time on the streets. Most of that was due to being a young prostitute, and being brought up as a young prostitute as a child. I didn’t get out of that cycle of self abuse until I was about 22. So I understand a lot about living on the streets and I understand a lot about young people and their problems with sex abuse.”

In the 1980s, Mr O’Mara set up the first-ever helpline for men who had been sexually abused or raped. He has wanted to establish a residential support project for just as long. “I’ve always wanted to do something with regard to housing and having a set-up where people could come into a housing situation, and also get counselling and ongoing support.

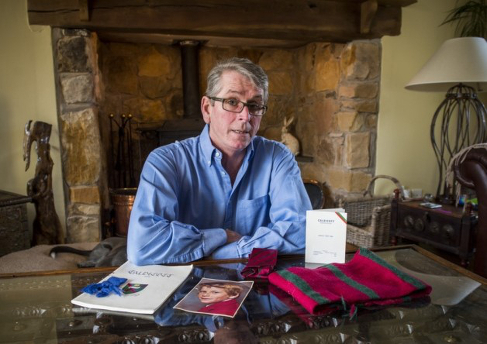

Nigel O’Mara was able to set up the East Midlands Survivors hostel when his landlord said, “I’ve got a house, and I’m willing to give you a start.”

“But last year I did manage to get together with my [private] landlord, and we talked about it. And eventually he came around and said to me, ‘I’ve got a house, and I’m willing to give you a start.’ Just a guy, who understood what I was trying to do - that I was trying to make a difference.”

With costs of about £50,000 a year, much of the funding has come from individual donations and the goodwill of the landlord - so far two residents have moved in, paying £75 a week in rent. Mr O’Mara does not yet pay himself a salary, but he is applying for funding from the local police commissioner and the lottery. Referrals come from the council, housing associations, the police and other services. Two of the six beds are filled so far, and residents have access to weekly counselling.

Sadly, the scale of the abuse issue means that housing professionals are likely to have come into contact with survivors, either professionally or personally. The NSPCC estimates that for every one of the 50,000 children identified as needing protection from abuse in the UK, another eight are being abused.

Lacking security

Then there are the adult survivors. Last May, the National Police Chiefs’ Council reported that recent incidents reported to the police had risen 31% and non-recent cases - perhaps reported years after the abuse occurred - rose 165% in the five years to May 2015.

But why is abuse a housing issue? Simply put, people who have been abused in childhood are at an increased risk of homelessness later on. And it may make their housing situation less secure in other ways as well.

The National Association for People Abused in Childhood (NAPAC) cites an American study from 1997 which found that lack of care and physical or sexual abuse during childhood increased the risk of adult homelessness by 27 times.

Nigel O’Mara: “Within the home, everybody knows that they’re safe to talk.”

Earlier this week, the campaign group Agenda published a report which casts further light on the matter, although focuses specifically on women’s experiences. A deep data dive into a government survey of the nation’s mental health - the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey - revealed that one in 10 women who reported being sexually abused as a child had run away from home during their childhood. “One of the ways to escape as a young person is to become homeless,” notes Sarah Parnell, training manager for NAPAC.

The most disadvantaged group was women who reported extensive physical and sexual violence from childhood into adulthood - of these, one-fifth had been homeless.

Some of the findings point to less straightforward linkages. A full fifth of women who had been sexually abused in childhood, but reported no other sexual or physical abuse in their lifetimes, lived in homes with mould. This compares with 12% of women who had experienced little or no abuse.

Aside from statistics, survivors themselves say the links are obvious. Ian McFadyen is in a particularly good position to know - he is a survivor of brutal child abuse by teachers at boarding school. He slept rough for two-and-a-half years on the streets of Edinburgh. And he worked for some 14 years for homelessness organisations.

Ian McFadyen, abuse survivor

Mr McFadyen seemed to be making a success out of life, with a good job and a nice flat. But he had never told anyone what happened to him at school. “My dad passed away. And he was the person I really wanted to try and explain to what happened to me in my childhood. And I never got that opportunity,” he says. “So I started drinking. Drinking never stopped. And the drinking led to me not showing up to my work. Losing my job, not paying my mortgage, losing my home. It ended up with this privileged public schoolboy, on the streets, alcohol dependant, with no idea about what it was like to be homeless or claim benefits.” By the time he came off the streets, Mr McFadyen was also using heroin.

When did he notice the correlation between homelessness and former abuse? “It didn’t take long. Most of the people I was out on the streets with had very few family connections. And unfortunately the majority of the abuse which takes place within the UK is interfamilial abuse.”

But it was once Mr McFadyen started working in the homelessness sector that it hit home how common it was for clients to disclose childhood abuse. Survivors and charities that work with them are keen to emphasise that different people react differently to abuse. However, for some, abuse in childhood is followed by a chaotic life in adulthood, and may include problems with alcohol, drugs and with the criminal justice system.

Mr McFadyen explains: “One of the massive issues for those who were abused in childhood is we reel against authority, and so that person who is going to be authority is going to be your housing officer, is going to be the person who is instantly on the back foot with people like myself.”

But the impacts do not always make themselves felt in such ways.

“Some of these people are going to have very severe post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Some of them are going to be showing no symptoms. It’s so varied, that every single person has to have their own programme,” says Mr O’Mara from the Nottingham hostel.

Tailored needs

Nigel O’Mara: “I’m hoping that people are able to go into a place on their own and feel comfortable surviving there.”

The hostel is “an ordinary house”, he explains. But there are differences. “I have a real problem taking a shower when there’s anybody else in the house,” Mr O’Mara says. “I wait until everybody’s out.” For a survivor who has to live in a shared house, for example, issues like this pose obvious problems. But at the hostel it is possible for residents to explain small things which will make them feel safe, and for adjustments to be made.

As Mr O’Mara explains, “Being a victim of sexual abuse never goes away - it’s not something that changes. After 40 years I know full well it still affects me every single day. How it affects me is up to me - it didn’t used to be, but it is now. I’m hoping that people go from here and are able to go into a place on their own and feel comfortable surviving there.”

But the hostel only has six spaces - what steps can other housing providers take? NAPAC, the main charity working with abuse survivors, makes the case that housing organisations should routinely be asking clients and tenants if they have experienced childhood trauma, alongside questions about debts, mental health issues and domestic violence. The concept is that by identifying this underlying issue, it may be possible to provide the proper support to clients.

The charity polled nine large housing associations, and found that none ask this question.

Still, survivors that Inside Housing spoke to did not agree on whether asking the question was a good idea.

Mr McFadyen is on the side of asking, although he acknowledges that people in general are “petrified” of this question. Fifteen years ago, the same stigma would have applied to asking about mental health, addiction, or HIV, he argues. “Now, it just rolls off the tongue in an assessment - mental health issues, addiction issues, do you have any financial issues, are you in debt?”

Mr McFadyen also refers to his own experiences. When he was a young person his parents had no idea what was happening. “We went to psychiatrists up and down the country. ‘Why is Ian going off the rails?’ Not one person ever asked me, ‘Did you suffer any trauma?’

“I don’t know if I would have said yes. But by at least asking the question, it breaks the stigma down.”

However, Mr O’Mara at the East Midlands Survivors Hostel is cautious about the idea, arguing that professionals should wait for survivors to disclose, rather than forcing the issue.

Everyone Inside Housing spoke to for this story agreed that the person asking should be trained and prepared with what to do if the answer is ‘yes’. (NAPAC is in the middle of organising the first training of this kind for housing workers.)

Whatever the answer ends up being, survivors are clear that housing can be transformative. As Mr O’Mara says, “If you don’t feel safe in your own home, then you can’t feel safe anywhere else.”

Housing impacts for female survivors

- One per cent of women with little experience of abuse have been homeless. This compares to 2% of women who were abused as a child only and 21% who were extensively abused in childhood and adulthood.

- Two per cent of women with little experience of abuse ran away from home in childhood. This compares to 10% of women who were abused as a child only, and 22% who were extensively abused in childhood and adulthood.

Source: Hidden Hurt: Violence, Abuse and Disadvantage in the Lives of Women, Agenda