You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Lessons from Lakanal

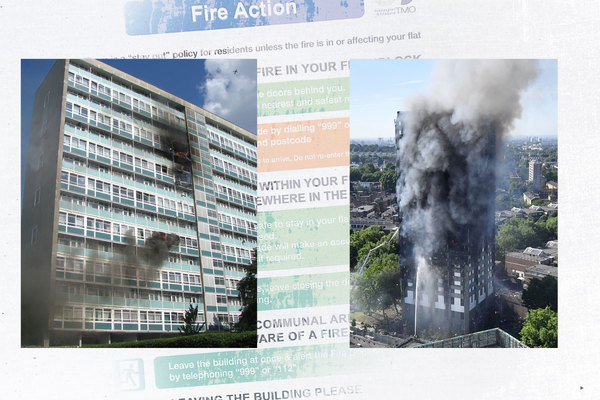

As Southwark Council pleads guilty to four criminal charges relating to the Lakanal House fire, Sophie Barnes looks at what went wrong and whether it could happen again

Source: Rex Features

Eight years ago the lives of three adults and three children were brutally cut short by a fire that raged through Lakanal House, a tower block in south London.

Last week, Southwark Council was sentenced to pay a £270,000 fine and £300,000 of legal costs after pleading guilty to four criminal charges relating to the fire. As the last chapter in these legal proceedings closes, Inside Housing looks at what went wrong at Lakanal, and whether the sector has learned the necessary lessons to prevent it happening again.

Southwark was sentenced for not carrying out a fire risk assessment and problems with the fire proofing of staircases, internal doors, ceilings and front doors of maisonettes.

The prosecution’s evidence largely relied on a report, seen by Inside Housing, by fire safety expert Dr David Crowder, who is head of fire investigation and expert witness services at the Building Research Establishment. Dr Crowder began investigating Lakanal House three days after the fire and concluded no fire risk assessment had been carried out in the block, and there were “numerous deficiencies” in relation to fire safety.

Between March 2006 and May 2007 a major Decent Homes refurbishment of the block was carried out which included replacing front entrance doors, communal doors and the removal of asbestos panels.

READ MORE ABOUT THE LAKANAL HOUSE FIRE

Council fined £570,000 for Lakanal House fire failures

Council pleads guilty to Lakanal House fire safety failures

The jury in the 2013 inquest said this refurbishment “provided numerous opportunities to consider whether the level of fire protection of the building was adequate” but no such action was taken.

The first problem Dr Crowder identified was that the “boxing in” of timber staircases was not done correctly. The staircases had been boxed in with ceramic board which was only nailed to the underside of the timber stairs. This meant the fire could consume the board and spread above the suspended ceiling.

The boxing in was “only very weakly” fixed to the underside of the stairs, which provided “negligible protection”. It was in a “poor state of repair” and the wood and board had dried out and the nails were loose. This meant there was no protection for the hallway and therefore the escape route was “compromised”. He added it was “possible to pull the boards off by hand with relative ease”.

A fire that blazed through this boarding “would be able to spread freely from a maisonette to the cavity above the suspended ceiling, or from that cavity into a maisonette”, he concluded.

In order for doors to be fire resistant for 30 minutes they need to be sealed where they meet the frame of a door. The seals then expand when in contact with extreme heat. But none of the doors were fitted with strips or seals, Dr Crowder found. This included maisonette front doors, fire escape doors and doors between stairwells. This “allowed more smoke to spread throughout the building than would otherwise have been the case”, he concluded.

The suspended ceilings were made out of chipboard fixed to a “significant quantity” of untreated timber. The “major concern”, the prosecution said, was that these ceilings were subdivided so fire could spread rapidly. Despite removing the suspended ceilings during a refurbishment, the ceilings were then put back over “ineffective” boxing. The prosecution said this was a “lost opportunity” to make big improvements in fire safety.

The materials used to build the suspended ceilings were a “significant fuel load”, said Dr Crowder, and would allow fire to spread into the general corridor. This blocked off the escape route and would “foreseeably impact upon firefighting and rescue efforts from the building, given that a substantial fire could develop unseen above the suspended ceiling”.

Critically, Dr Crowder said no information was provided by the council on the number of risk assessments completed on an annual basis and “no justification” was given for not completing risk assessments for Lakanal House and Marie Curie House, a tower block which neighbours Lakanal. This was particularly concerning because Dr Crowder pointed out Lakanal House and Marie Curie House had previously been given the highest risk rating for fire spreading.

He concluded the fire precautions in place were “unsafe and putting relevant persons at risk of serious injury or death, a risk which could have been foreseen and addressed had a suitable and sufficient fire risk assessment been carried out”.

Richard Matthews QC, acting for the council, said it has “sincere regret for the failures that were present in the building” before the fire.

Composite panels

The whole blaze began from an electrical fault with a TV on the ninth floor. This caused a composite panel on the outside of the wall to melt and flames spread up the outside of the building.

By the time the emergency services arrived on the scene - just five minutes after the first 999 call - the flames were already approaching one of the first victim’s flats, that of fashion designer Catherine Hickman. Burning debris then fell from the ninth floor onto several floors below, starting separate fires.

The coroner’s inquest found Southwark Council’s contractors had fitted panels to the outside of the building that were not compliant with the national building regulations, which require more secure Class O panels. However, Ronnie King, honorary administrative secretary of the All-Party Parliamentary Fire Safety and Rescue Group and formerly chief fire officer at Mid and West Wales Fire and Rescue Service, says even these regulations were not good enough.

The London Building Act, which was replaced in 1985 with the national building regulations, required panels to have fire resistance of up to one hour. Class O panels do not provide this level of fire resistance and Mr King is convinced if this level of fire resistance had been in place “it is almost certain that the six tragic deaths would not have occurred”. This remains a problem.

“We still have 4,000 older tower blocks in the UK which have the same regulations applied to them,” he says.

Mr King is concerned at the “failure of three successive government ministers” to review building regulations related to fire safety, now more than 10 years since they were last reviewed. According to Mr King a review “would take account of all the errors that occurred in Lakanal House, and is a sure way of ensuring that everything is being done to prevent such a recurrence”.

In the House of Commons last year housing and planning minister Gavin Barwell committed to a review “following the Lakanal House fire”. This has not yet taken place and when pushed for a date, a Department for Communities and Local Government spokesperson only said it would happen “in due course”.

Sam Webb, a fire safety expert who helped gather evidence for the victims’ families during the inquest, says “really serious questions” need to be asked in parliament. He says there is a conflict between a drive for better energy efficiency in homes and fire safety. “We require buildings to be warmer to save energy, but there’s a conflict between the materials that you use to do that and fire safety. If they’re using materials that will cut down on heating bills, that’s fine, but if it’s going to reduce your safety in a fire to a matter of minutes, that’s unacceptable.”

Since the fire Southwark Council has spent £62m on its fire risk assessment programme and other fire safety measures for all its social housing in the borough.

But while lessons may have been learned in a small patch of south London, nationally there is still much to be done to ensure the avoidable tragedy of Lakanal House is not repeated.

Timeline of the fire

4.15pm

A faulty television causes a fire to break out in a bedroom in flat 65 on the ninth floor

4.18pm

First 999 call

4.21pm

One of the victims, Catherine Hickman, makes a 999 call from her flat on the 11th floor. She is told to stay in her flat and await rescue

4.23pm

The London Fire Brigade arrives and sets up a command centre on the seventh floor

4.43pm

The phone operator loses contact with Ms Hickman

4.50-5pm

Ms Hickman is overcome by the smoke and flames, and dies

5-5.26pm

The husbands of Helen Udoaka and Dayana Francisquini are in contact with their wives

5.26pm

Contact lost

5.45-6pm

Three children die from fume inhalation: three-week-old Michelle Udoaka, Felipe Francisquini Cervi, three, and Thais Francisquini, six

5.50-6pm

Ms Francisquini dies

5.55-6.05pm

Ms Udoaka dies

(Timeline provided by Sam Webb)