The green building dream

Back in 2007 David Cameron had just started his march to power, Lady Gaga was finishing off her breakthrough album and, in the housing world, eco-towns were the next big thing.

But while Mr Cameron and Ms Gaga have gone on to bigger things, then prime minister Gordon Brown’s ambition to build 10 eco-towns of up to 20,000 homes - with up to £70 million government investment - seems to have disappeared off the face of the earth. They’re entirely absent from the coalition government’s rhetoric and the pages of the national press.

Through its Get on our Land campaign, Inside Housing is pushing for land to be freed up for housing development. The UK needs more homes, yet those who want to build them share a common complaint: lack of land. It’s too expensive, too contaminated, too fraught with planning complications, they say.

If eco-towns had lived up to their billing, they could have provided part of the answer. A spokesperson for A2Dominion, involved in the North West Bicester eco-town scheme, says there were such high hopes for the schemes because they would ‘show the market that homes with high eco principles can be delivered on large sites’ - and, in turn, this would benefit residents who would have smaller heating bills. But what happened to them? Have they been dropped entirely or are they continuing as first intended, but now lurking under the radar?

Certainly eco-towns will not be pushed by a ruling coalition which uses ‘localism’ as a watchword. A spokesperson for the Communities and Local Government department confirms the shift in emphasis by stating it will ‘not impose schemes or any solutions on local communities’ when asked to comment on the future of these developments.

Controversial start

Even before the change of government in May 2010, the eco-towns project had attracted controversy. The suggestion that it would see schemes built that would not otherwise get planning approval led to accusations of a ‘greenwash’ and fierce local opposition. By July 2009, just four out of 57 hopeful schemes were deemed suitable to proceed by the CLG in the first phase of the eco-town programme, which initially aimed to deliver 10,000 homes by 2016.

These schemes were already less ambitious in scale than the original concept. Two of them were urban extensions and a third was more of a redevelopment of an existing town than one of the freestanding, new towns first envisaged.

Despite this, the idea of environmentally sustainable exemplar developments has survived, even if the eco-towns brand has become unfashionable. According to the CLG ‘there are currently 15 local authorities and partnerships leading eco-development projects’. The language reflecting both a move away from building new towns and a distancing of central government from Mr Brown’s big idea.

A new standard

The 2009 eco-towns ‘supplement to planning policy statement one’ did set out the parameters by which the ongoing success of the eco-towns can be judged, however.

Its definition of eco-towns said they would have at least 5,000 homes, of which at least 30 per cent should be affordable, providing ‘the critical mass necessary to be capable of selfcontainment while delivering much higher standards of sustainability’.

These standards included being carbon neutral across the development, building homes to level 4 of the code for sustainable homes or higher, local employment, ambitious requirements for green infrastructure and water efficiency.

By the time then housing minister John Healey announced the second phase of the programme - to contain at least 45,000 homes - in December 2010, the criteria were being given more creative interpretations by promoters and officials. The nine proposals in the second phase were a mixture of redesigned existing plans and new proposals for eco-communities. In two schemes the potential for applying eco-town standards across a whole area was to be explored.

Unlike many first wave proposals, second wave schemes had the benefit of local authority involvement, which was encouraged by central government. As a result, when the coalition took office, the previous hostility of housing minister Grant Shapps towards the Labour government’s eco-town plans mellowed into half-hearted support as the government continued to fund schemes - albeit at half the £70 million originally intended. It put forward £5 million for second phase and £30 million for first phase eco-towns.

The coalition’s plans to slim down planning guidance into a single national planning policy framework will see the PPS1 eco-towns supplement replaced with a series of much more broadly applicable principles regarding sustainability, carbon reduction and climate change adaptation. Eco-town status will no longer carry weight in the planning process.

Along with the abolition of regional spatial strategies, this has left schemes free to consider which of the criteria in the PPS1 supplement they wish to implement. Faced with economic uncertainty and funding cuts, some have dropped or diluted requirements they see as unhelpful because they were difficult or expensive to achieve.

The first wave

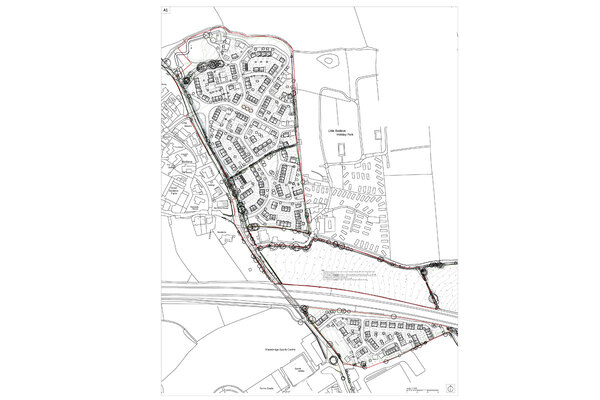

One first wave development that is making a virtue of sticking to the PPS1 criteria is North West Bicester in Oxfordshire, an urban extension that is unafraid to use the eco-town label to this day. It promises to deliver 5,000 new homes - 30 per cent of which will be affordable - over

20 years. Plans were reworked following criticism of its eco-credentials by the Environment Agency, Oxfordshire Council and The Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment .

Planning consent was granted last August for an exemplar phase of 393 homes - 119 of which are affordable - at level 5 of the code for sustainable homes, and a renewable energy centre. Work on the scheme will start this spring, with the first homes becoming available in 2013. It has received £6 million funding from the Homes and Communities Agency so far for the exemplar phase.

Gerry Walker, director of development for 34,500-home housing association A2Dominion, the developer of the scheme, says: ‘We’ve aimed to keep the development close to the core of PPS1 [as an exemplar project] and the first phase, the exemplar scheme, has some really innovative technology and ideas underpinning its design and layout. We’re building a green community here - complete with a [carbon neutral] ‘eco-pub’, schools and shops that specialise in providing locally produced, sustainable food.’

By contrast, the developers of Rackheath, near Norwich, where an estimated 4,150 sustainable homes are planned over the next 10 years, now describe the scheme as an ‘eco-community’. Nonetheless, it is still going ahead - a planning application for the initial 200 homes is due to be submitted this year.

The third eco-town in the first phase, at Whitehill Bordon in Hampshire, involves redeveloping an existing settlement as the closure of army bases releases 230 hectares of land. The Ministry of Defence has now confirmed that it will have left the area by 2015 at the latest, at which stage building could start.

However, the scale of the project, being led by East Hampshire Council, has reduced from 5,300 to 4,000 new homes since it was awarded eco-town status in 2009. This would obviously take it below the original scale intended for a scheme to qualify as an eco-town but the council says this reflects the views of residents about how many homes the area needs.

A spokesperson for East Hampshire Council insists: ‘Whitehill Bordon is still striving to achieve the high environmental targets set out in the planning policy statement.’

The scheme is placing a strong emphasis on protecting and enhancing wildlife biodiversity and aims eventually to be both water and carbon neutral, meaning that usage in the redeveloped town will not exceed current levels, according to the council.

The final eco-town in the first phase, the China Clay ‘eco-communities’ project, consists of up to six linked sites near St Austell, Cornwall. A hybrid planning application for one site was submitted in February 2011, involving a detailed application for a 92-home ‘demonstrator’ site and an outline application for up to 2,000 homes, 40 per cent of which would be affordable. The developers have now placed this application on hold as the local planning authority reviews its regeneration plan in the light of the NPPF.

Keeping up momentum

In the absence of significant progress in building their new communities, the first wave schemes have sought to maintain impetus with a range of demonstrator and retrofitting projects, paid for with CLG funding. This means that some of the second wave schemes are now starting to catch up with them.

Cranbrook, to the east of Exeter, was cited as a prototype eco-town in Labour’s 2007 eco-towns prospectus but did not make it into the second wave until early 2010. But with more than £50 million in public funding in place it is now ahead of the first wave developments, with work on key infrastructure having started and construction of the first 1,120 of a possible 6,500 homes due to begin any day now.

A spokesperson for East Devon Council says: ‘Although not designated as an eco-town, the design for Cranbrook is a complete package of sustainable development which includes: open green spaces for recreation and education, a comprehensive public transport system, with a rail link, a network of cycle and foot paths, well-designed, low-carbon public buildings, sustainable energy solutions and the early delivery of social and community infrastructure.’

Similarly, Taunton Deane Council says an overall aim of Monkton Heathfield, its proposed 4,500 home extension to the Somerset town, is to create a ‘critical mass’ that promotes self-containment and reduces environmental impact. The council says it has sought to ensure its plans conform to the PPS1 criteria but it has recently cut its borough-wide target for affordable homes in new developments from 35 per cent to 25 per cent.

The Leeds City Region Partnership is taking a more incremental approach with its second wave urban eco-settlement programme, which it says was developed as ‘a more sustainable alternative to a freestanding eco-town, that better met the housing and regeneration needs and ambitions of the city region, and sought to raise standards across the region’.

So far, 255 new homes have been completed at two of four sites identified as having potential for 28,000 homes. Colin Blackburn, housing and regeneration lead at Leeds Council, says the local enterprise partnership remains committed to taking the project forward, but adds: ‘With the ending of the eco-development fund and the major reduction in capital funding for housing and regeneration-type activity, potential support opportunities have been limited.’

Poles apart

The two second wave projects with the vaguest plans in 2009 have produced very different results with their CLG funding. Cornwall Council spent the £250,000 it received in funding on an assessment of potential sites for further ‘highly sustainable developments’ of at least 800 homes, based closely on PPS1 criteria, and identified four sites with the fewest complications. This work will feed into a core strategy for consultation in early 2012.

Sheffield City Region, which is backing a major ‘eco-vision’ regeneration of the Dearne Valley, used £227,500 in funding to develop an evidence base to support the case for introducing higher design standards for new development across the area. It has also retrofitted a demonstrator home to showcase energy efficiency and renewable energy technologies and encourage people to introduce them in their own homes.

Essex Haven Partnership is perhaps the scheme with the least to show for the £100,000 it received in funding from the CLG. David Ralph, project chief executive, says: ‘This grant was never for an eco-town but to support local work on examining how higher standards of sustainability might be promoted and could be achieved in future development.’ But he adds that proposed changes to the planning process have delayed local authorities in producing local development frameworks.

So, despite some lowered ambitions, the eco-towns programme is far from dead. Alex House, projects and policy officer at the Town and Country Planning Association, states that ‘progress at the first and second wave eco-towns is mounting, with planning applications being approved, demonstration projects completed and construction work starting’.

The programme can certainly claim to have started many people thinking holistically about making new communities environmentally sustainable. While they continue to make progress it is clear, however, that in most cases they will be less ambitious than the original vision.

Timeline

May 2007

The Communities and Local Government department announces competition to build up to five eco-towns

September 2007

Then prime minister Gordon Brown doubles eco-town target to 10 sites

April 2008

Shortlist of 15 eco-towns published

July 2009

First wave of four eco-towns announced in Hampshire, Cornwall, Norfolk and Oxfordshire

December 2009

Second wave of nine eco-developments unveiled.

The government relaxes its criteria and allows developers to plan for broader developments rather than the self-contained sites in the first wave

April 2010

Haven Gateway Partnership accepted into the second wave.

July 2010

Government halves funding for both waves of eco-towns. The first wave will now receive £30 million and second wave schemes £5 million

August 2011

Planning permission granted for an exemplar scheme of 393 homes as part of the North West Bicester eco-town plans (a phase one scheme)

More second wave eco-towns

Central Lincolnshire: large sustainable urban extensions to Lincoln, Gainsborough and Sleaford (details of which will be in its forthcoming core strategy).

Fareham, Hampshire: 6,500 to 7,500 new homes in an area north of the M27, 30 to 40 per cent of which will be affordable. Work is expected to start onsite in 2016 and to be complete by 2030.

Northstowe, Cambridgeshire: new ‘town’ of up to 10,000 homes (35 per cent affordable). Outline planning application for first phase of 1,500 homes to be submitted in February 2012, for possible start in 2013 and first homes available 2014.

Shoreham Harbour, West Sussex: potential for ‘eco-quarter’ of up to 2,000 homes built over 15 to 20 years through the development of a joint area action plan which will be put out to public consultation during 2012 and adopted by the end of 2013.

Yeovil, Somerset: proposed urban extension of 3,700 homes. The local authority is still considering which of four locations to use.

Get on our Land

Aims

- To sign up 100 supporting organisations, each committing to do everything they can to increase the supply of land on which to build homes throughout the UK

- To work with our readers to produce a charter outlining ways of easing housing land supply throughout the UK

- To encourage UK councils to identify all surplus public assets in their areas, including those suitable for housing development, in line with imminent guidance from the Communities and Local Government department’s capital and assets pathfinder programme

How to get involved

- Pledge your support for Get on our Land by signing our online petition at www.insidehousing.co.uk/geton

- Encourage others to do the same, particularly if you’re a council driving the strategic housing vision for your area

- Send us your examples of successful schemes so that we can share what works when it comes to bringing difficult sites forward for housing development. Email martin.hilditch@insidehousing.co.uk