You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

‘You can’t solve the national housing emergency by building shared ownership’: an interview with Polly Neate

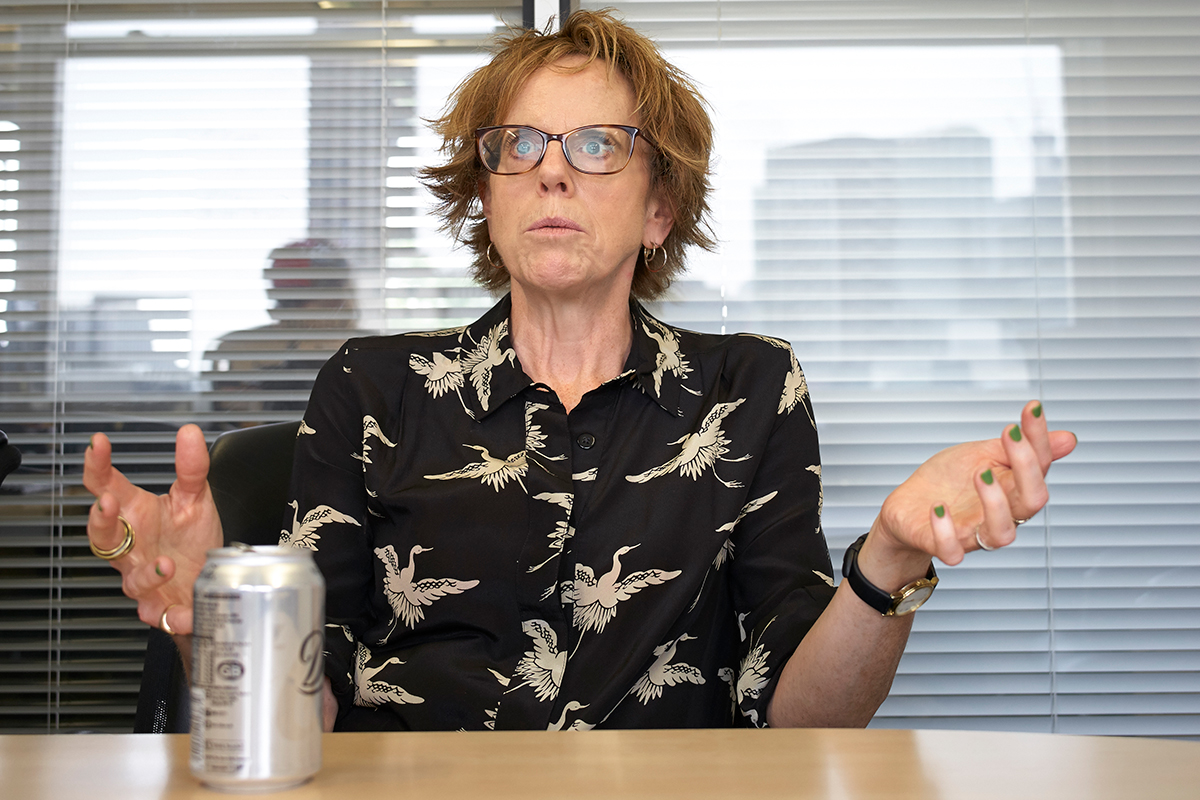

Shelter published its new three-year strategy on Housing Day and World Homeless Day this week. Martin Hilditch spoke to its chief executive Polly Neate to find out more. Pictures by Julian Anderson

Polly Neate speaks to Inside Housing

When Polly Neate took over as chief executive of Shelter, she walked in the door promising to take its work “to the next level”.

Well, now it’s the moment of truth. After extensive consultation with staff (which involved face-to-face conversation with more than 1,200 people), volunteers, service users and various stakeholders, Shelter has published its new three-year strategy.

With impeccable timing, this all happened on Housing Day and World Homeless Day. It’s the first strategy that she has overseen and she promises it will herald a big shift that will take the charity “back to our roots”.

“We were founded to change things – to change society,” Ms Neate states.

Inside Housing met up with Ms Neate just before the launch to find out what Shelter will look like as a result, and what that might mean for the people who use its services and the housing sector. One thing’s for certain – you’re going to notice a difference.

Before we talk about where Shelter is going, however – where is it travelling from? Why is a big change necessary and, if it says it is going back to its roots, does this mean it had lost sight of them in recent years?

“I think in terms of our public profile, what we were focused on in the last strategy, which was obviously before I joined, was getting housing on the political agenda,” she says. “I think that has been really successful.”

And the difference now? “What we need to do now is to make sure that the fact it is on the political agenda actually benefits the people that we are here for,” replies Ms Neate.

That huge consultation with staff revealed that they “really want us to be powerful advocates for the people we help – and the people that we help are the people most affected by the housing crisis,” she says. This is perhaps not surprising given “our biggest group of staff is doing direct service delivery… and they are absolutely nose-to-nose with how awful it is for people every single day”.

“We need to be representing the needs of the people we work with. Shelter wasn’t founded because my kids can’t afford to buy a home in London – tragic though that is,” she adds with a laugh.

How, though, is Shelter going to set about returning to its roots and “single-mindedly advocating for the people who are at the bottom of the pile”?

One of the main planks of its strategy include securing manifesto commitments from all political parties to a major public housebuilding programme ahead of the 2022 general election and the 2021 Scottish election.

And, in Shelter’s book, public housebuilding means homes for social rent.

“This is social housing, definitely,” states Ms Neate. “No matter who delivered by, but we are talking about housing for social rents, not the wider affordability piece. Not that that doesn’t matter, but you won’t solve the national emergency by building Help to Buy or shared ownership housing.”

In order to do this, Shelter reckons it needs to create a “movement” of at least 500,000 people – who would help the cause by campaigning, volunteering and donating.

Which brings us to the next plank of the strategy: putting Shelter’s service hubs across the country at the heart of communities and turning them into “bases for activism as well as help and support” according to its strategy.

This will help “inspire a new wave of grassroots supporters – a mass movement for change whose voice will be heard everywhere, from Westminster to local town halls”.

“No government is going to build the amount of social housing we need unless they think there is some serious pressure from the country to do that"

“We have been piloting a community organiser role in two of our hubs,” says Ms Neate. “So we are going to roll that out so that our hubs are spaces where we can organise and create change within local communities and also bring on board supporters.”

The 500,000-strong movement is important because there is a limit to what a charity – even one with the size and profile of Shelter – can do by itself, states Ms Neate.

“Ultimately the half a million people convince the government that the only way forward is to build some more social housing,” Ms Neate states. “No government is going to build the amount of social housing we need unless they think there is some serious pressure from the country to do that. We need to create that pressure.”

“I still think for social housing the main obstacle is that people don’t believe that there are votes in building social housing, and we have to convince them that there are,” she adds.

If all of this sounds overambitious in three years, then that’s all well and good, Ms Neate thinks. The possibility of failure, in fact, is a positive, she argues.

Watch a video about Shelter’s 2019-2022 strategy

“I think too many charities when they are setting their strategic aims are asking themselves in three years’ time will we be able to tick that box – and if we can’t, we won’t say it’,” she states. “I don’t agree with that.

"We need to set out what we think realistically has to happen to end the national emergency and what our role in that is going to be.

"That is what our staff want us to do as well. They don’t want us to be playing realpolitik – they want us to be saying what has to happen.”

Providing advice will continue to be a core function. But Shelter’s new strategy wants to develop stronger, quicker and more tailored advice for people whose rights are under threat – including a dedicated emergency phone hotline.

It currently has an emergency number “but we can’t answer enough of the calls at the moment”. So the plan is to increase investment in this area, she adds.

The final main strand of Shelter’s strategy involves developing its use of strategic litigation to challenge discrimination in housing.

On the launch day, you will have seen Ms Neate popping up to talk about how single mothers are eight times more likely to be homeless than couples with children.

And it is in this area that some council housing and social services departments might want to sit up and take notice. Shelter plans to challenge the way children are treated in the housing system. It points out – pretty reasonably! – that the Children Act 1989 should protect the welfare of children if their parents become homeless.

But in some cases councils are threatening to separate parents from their children by saying under the letter of the law their duty of care – and thus offer of accommodation – is with children and not their parents. It’s an issue that Inside Housing has previously flagged as part of its Cathy at 50 homelessness campaign. Now Shelter is vowing to help stamp it out.

“It is definitely widespread,” Ms Neate says of the practice.

“They [councils] don’t do it,” she adds – suggesting, as many others have before, that the threat is effectively a form of gatekeeping designed to make terrified parents go away.

Click here to read our 2016 article 'A modern day Cathy'

“They don’t do it [follow through on the threat],” she states. “But I would argue that the threat is not in the best interest of the child because it leads to them remaining homeless. Just threatening it is actually preventing the child’s needs from being met, which is the opposite of what local authorities are meant to do under the Children Act.”

Shelter is now actively looking for test cases in this area and says it will be “seeking to challenge authorities’ interpretation of their duties through landmark legal cases”.

For Ms Neate the focus now shifts to delivering the ambitious strategy. But she won’t be able to do it alone, she says.

“I think you can convince a politician [of the need for change] but they won’t act on it unless you can shift social attitudes as well,” she says.

“It’s about power actually,” she adds. “There is a brilliant phrase that one of our community organisers told me, which is ‘there is the power of organised money and there is the power of organised people’.” For Shelter the immediate future is about “building that power of organised people”.

Cathy at 50 campaign

Our Cathy at 50 campaign calls on councils to explore Housing First as a default option for long-term rough sleepers and commission Housing First schemes, housing associations to identify additional stock for Housing First schemes and government to support five Housing First projects, collect evidence and distribute best practice.

At a glance: Homelessness Reduction Act 2017

The Homelessness Reduction Act 2017 came into force in England on 3 April 2018.

The key measures:

- An extension of the period ‘threatened with homelessness’ from 28 to 56 days – this means a person is treated as being threatened with homelessness if it is likely they will become homeless within 56 days

- A duty to prevent homelessness for all eligible applicants threatened with homelessness, regardless of priority need

- A duty to relieve homelessness for all eligible homeless applicants, regardless of priority need

- A duty to refer – public services will need to notify a local authority if they come into contact with someone they think may be homeless or at risk of becoming homeless

- A duty for councils to provide advisory services on homelessness, preventing homelessness and people’s rights free of charge

- A duty to access all applicants' cases and agree a personalised plan