You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

In case you missed it

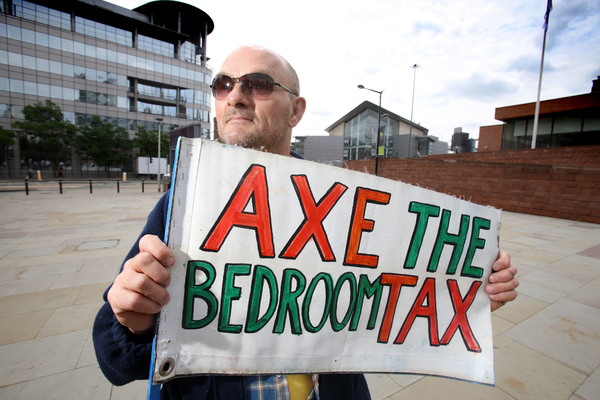

Today looks like a very good day for the DWP to sneak out independent research on the impact of the bedroom tax and cuts to the local housing allowance.

While Iain Duncan Smith seems to have survived the Cabinet cull of middle aged men, the two reports offer in-depth scrutiny of two of his most controversial policies. There is as yet no DWP press release or comment but you can find the reports here and here on its website.

This blog will concentrate on the independent evaluation of what the DWP calls the removal of the spare room subsidy. The report by the Cambridge Centre for Housing and Planning Research and Ipsos Mori analyses the effects on and the responses of tenants, landlords, local authorities, voluntary and statutory organisations and advice agencies and lenders.

While this is the interim report and covers only the first eight months of implementation from April to November 2013, it’s also the most comprehensive analysis of the policy yet attempted is published by the department responsible for it. Here are some of the findings that I’m guessing it hopes that the reshuffle will distract you from reading about:

The impact on tenants. Around 80 per cent of those affected are paying some or all of the shortfalls on their rent but only half have paid it in full and 20 per cent had paid nothing in the first six months.

Of those who have paid, 57 per cent say they found the money by cutting back on household essentials and 35 per cent by cutting back on non-essentials.

A third have borrowed money to pay the shortfall. Most of this has come from family and friends (21 per cent) but tenants questioned whether this was sustainable given the low incomes of those they are borrowing from. Another 6 per cent have borrowed from another lender, 3 per cent from a credit card and 3 per cent had taken payday loans.

In total, that means more tenants making up the shortfall have done it through borrowing than by applying for a discretionary housing payment (22 per cent) or looking for a job or better pay or hours (21 per cent)or looking to move (16 per cent).

Downsizing. The DWP might have seized on higher than expected figures for successful moves to smaller accommodation: 4.5 per cent of affected tenants had managed to downsize to another social tenancy in the first six months. The report notes that if this trend continued at the same rate for the next two years, over 20 per cent of those affected would have downsized within the social rented sector. A further 1.4 per cent moved into private rented homes in the first six months.

However, this trend may not be all it seems. It is only higher than expected because the DWP’s impact assessment assumed that there would be no significant moves. There were also big differences between areas:

- landlords with the lowest proportion of tenants affected had seen downsizing rates almost four times higher than those with the highest proportion

- demand for downsizing has been difficult to meet so far especially in large rural areas and in urban and suburban areas where the standard social rented property is a three-bedroom house

- financial incentives to downsize offered by landlords are less available in areas most affected by the bedroom tax.

Meanwhile most tenants were reluctant to move away from services, work and support networks and landlords and agencies said most affected tenants would prefer to say put and pay the shortfall.

Discretionary housing payments. The research confirms other indications of gaps in the system and huge variations between different areas:

- more than half of affected tenants were not aware of DHPs

- there was widespread concern about disabled people in adapted properties being denied help because their disability benefits were counted as income

- agencies were worried that some of the most vulnerable, including those with mental health difficulties, are missing out

- there was widespread concern that the time-limited nature of DHP awards means it is only delaying the real impact of the policy and about the future size of DHP allocations.

The DWP has also just published a good practice guide for local authorities on DHPs.

Employment. Some 18 per cent of affected tenants said they had looked to earn more money as a result of the policy but ‘only modest numbers would appear to have been successful in the first six months’. The vast majority (87 per cent) of those looking for work or better pay have not found them.

Allocations and development. Some 41 per cent of landlords reported difficulties letting larger properties, with the problem greatest in areas most affected by the bedroom tax like Wales and the north of England (60 per cent) and lowest in areas least affected like London. However, the report found no statistically significant increase in national voids figures.

Of the 80 per cent of landlords involved in new development, a third said they had changed the profile of their programme due to the bedroom tax and benefit cap. The main impact has been a reduction in the number of larger homes and increase in one-bedroom flats being built. Many landlords were worried that losses in rental income could reduce their ability to develop in future but their relationship with lenders does not seem to have suffered yet.

Overcrowding. The DWP has argued that the bedroom tax will help overcrowded families by freeing up larger homes. However, the report found that most local authorities and landlords believe it will have little impact and revisions to the definition of overcrowding as a result of the policy mean it will be difficult to assess the impact anyway.

Knock-on effects. Changing allocations procedures (for example 72 per cent of landlords have increased priority for downsizers) have increased waiting times for smaller homes but made larger homes available to other people on the waiting list. Two-thirds of landlords would consider letting larger homes to people not affected by the bedroom tax (pensioners and working people not on housing benefit).

Agencies working with the single homeless reported difficulties in hostel move-on to social housing because of the shortage of one-bed homes and landlord reluctance to let two-beds to single people.

Arrears and evictions. It was too early to expect much hard evidence on either but the report found widespread concern about ‘the impact of potential future evictions on local services, and on landlord finances as well as on the lives of vulnerable people’. The survey of claimants found 80 per cent were finding it very or fairly difficult to pay the rent and 79 per cent were running out of money very or fairly often (rising to 90 per cent for those in arrears).

Policies again vary hugely between areas. The chief executive of one local authority told the researchers ‘it is not the council’s business to evict people’ but a social landlord in the same area said it would follow usual procedures and ‘take supportive but robust action’.

And the research also reveals that small numbers of evictions have already happened and more could be on the way. The survey shows 45 evictions due solely to bedroom tax in the first seven months including 24 by one landlord. That is a tiny number but the report says that:

‘In terms of the level of arrears required to trigger court action, most landlords interviewed said that they were developing their policy over time. They were anxious not to be in the media for being the first in court for “bedroom tax evictions” and wantedf to give tenants every opportunity to pay. Nevertheless by the autumn a third had already begun the process of issuing formal warning letters and in some cases continuing further in the route to evicting non-payers.’

Ominously too, the report found that while most local authorities would not consider someone with bedroom tax arrears to be intentionally homeless, some said they would look to discharge their homelessness duty into a private tenancy and possibly into shared housing.

Overall then, the report will increase rather than allay fears about the impact of the bedroom tax. If it had really wanted to, the DWP could have spun a positive story about some of the findings, for example on downsizing or the falling numbers of tenants affected. The response by IDS to the BBC’s story on the study is a nod in this direction but he familiar line about ‘scaremongering’ by critics is looking pretty tired.

Far better then to publish the report on a day when everyone’s attention is focussed elsewhere.