Government ‘cover-up’ of dangerous cladding ‘one of the major scandals of our time’, lawyers tell Grenfell Inquiry

A “prolonged period of concealment” of the dangers of combustible cladding driven by an “unbridled passion for deregulation” and deference to industry lobbying ranks as “one of the major scandals of our time”, the Grenfell Tower Inquiry heard today.

In shocking opening statements delivered by lawyers acting for the bereaved and survivors today, governments stretching over a 30-year period were accused of repeated “deliberate cover-ups” of the risks of dangerous cladding.

New revelations included:

- The government received an estimate in the 1990s that the cost of fixing dangerous cladding was £500m. The bill today for all buildings is estimated at well above £15bn.

- Three reports into two key cladding fires in the 1990s were “covered up”. One marked ‘limited circulation’ contained key information about the use of combustible cladding, another revealed the likely failure of cavity barriers and a third was “entirely neutered”.

- The government acknowledged that a rule against introducing new regulations for the building industry in the 2010s put it in breach of its duty to protect the right to life.

- The government suppressed information about the combustibility of cladding used on Lakanal House after a fire killed six people in 2009, noting the need to “avoid giving the impression that we believe all buildings of this construction [are] inherently unsafe”. The investigation into this fire was shut down by officials in a “grotesque abdication of responsibility” which “raises the spectre of a deliberate cover-up”.

- After Lakanal, despite the government promising to implement the coroner’s recommendation to encourage the use of sprinklers, civil servants wrote that it was simply acting “to be able to say that [the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG)] is taking action” and it had prepared “a defensive line against them” [sprinklers].

- A senior civil servant warned in May 2017 – just a month before the Grenfell Tower fire – that “we, or ministers, are increasingly vulnerable to some or all of these risks becoming material and [government] being held to account for being inactive”.

- On the day of the fire, another civil servant emailed: “Some of the stuff about disproportionate burdens feels uncomfortable today.”

- The government elected not to drop a weak fire standard for cladding in the early 2000s out of fears that tougher standards would “discriminate against” certain products and a warning from industry that different testing would effectively outlaw rainscreen cladding with “economic consequences for the building industry and the UK as a whole”.

- Insulation manufacturer Kingspan wrote in 2003 that the government would not adopt tougher European fire standards “until the industry is ready to adopt it”.

- A government-commissioned test on the same aluminium composite material (ACM) cladding used on Grenfell Tower in 2002 failed five minutes into its 30-minute duration, but the product was not banned.

Painting a picture of more than 30 years of failure to act on warnings, lawyers said the fire came as a result of “an unintended consequence of a political ideology” where “deregulation… enabled industry to write its own rules”.

“Government’s dependency on industry resulted in government becoming a junior partner in the relationship, thereby permitting industry’s exploitation of the regulations,” said Stephanie Barwise QC, appearing for one group of the bereaved and survivors.

“Government’s response on realising the extent of the problem [with cladding] was to react by concealment instead of candour. The result is a prolonged period of concealment by government which should properly be regarded as one of the greatest scandals of our time.”

She was followed by Michael Mansfield QC, appearing for another group of families, who said: “The institution that has failed has been our democratic institution. It has failed by the paralysis, by the cover-up, by the dismissal, by the actual need to burn health and safety. Is that how our democracy is to be measured? I hope not.”

Ms Barwise drew attention to the Class 0 standard in government guidance, which has been the minimum requirement for cladding panels since 1952.

This standard primarily assessed the surface spread of flame, which means a product with a combustible core – like that used on Grenfell – could claim to possess it.

She said that the “culpable failure to detect” this flaw began in 1991 with a fire in a cladding system at Knowsley Heights in Merseyside. This block had been clad under a government funding programme and was being monitored by officials.

But when a fire broke out and spread over multiple floors, an official report prepared by the Building Research Establishment (BRE) revealed the cladding panels had been made of combustible glass-reinforced plastic marked for “limited circulation”.

A memo from the time – previously obtained by Inside Housing – noted that government press officers had requested the government “play down the issue of the fire”.

“Government’s tendency was to regard fires as something to be covered up or trivialised, such that the public might be ‘reassured’ and to avoid criticism of the underlying regulations,” said Ms Barwise.

She said not removing the Class 0 standard after this fire was “consistent with government legitimising the flammability of the cladding, rather than solving the safety problem it posed”.

She added that a further report produced by the BRE in 1994 revealed the dangers of rapid fire spread up through a cavity and the ineffectiveness of cavity barriers. This was kept secret and even contained a prohibition against reference in other published work.

“The consistent pattern of inadequate investigation and suppression of reports... goes beyond mere accident, and involves government collusion,” said Ms Barwise.

This fire was followed by another at Garnock Court in Scotland in 1999, which also spread via combustible glass-reinforced plastic panels.

She said the BRE’s report into this fire was “entirely neutered and did not even mention Class 0”. She described it as a “cover-up” and said the government “did not want to know” the extent to which the cladding had contributed to the fire.

Following this fire, the BRE conducted a survey to assess the cost of removing dangerous cladding systems from local-authority buildings.

“The likely reason [for the cover-up] was the need to avoid the bad press then circulating in a national newspaper, headed: ‘Danger flats that could explode like a tinderbox’ and to avoid the cladding scandal then estimated at a likely cost of £500m, but which has reached biblical proportions today,” said Ms Barwise.

Following this fire, the government commissioned the BRE to carry out a series of tests in order to develop new large-scale testing. The results were recently leaked to the BBC and have been seen by Inside Housing.

She said that a system that failed one of these tests in five minutes and 45 seconds included the same aluminium composite material (ACM) with a polyethylene core later used on Grenfell Tower.

Ms Barwise said it “beggars belief” that this ACM cladding was not specifically prohibited following these tests. One of the BRE reports to the government on these tests warned that “certain combustible claddings can support unlimited vertical flame spread”.

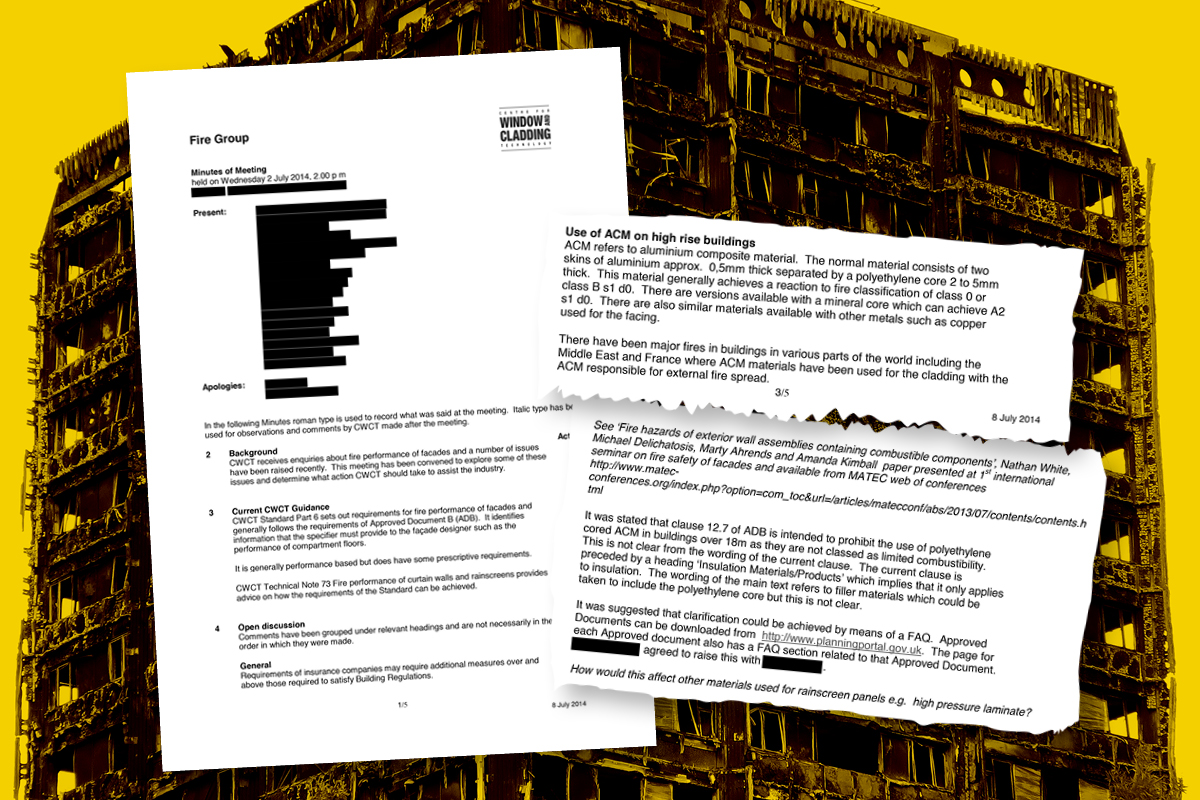

She said the likely reason the government failed to ban the use of the product or set tougher standards was “industry interference”. The Centre for Window and Cladding Technology (CWCT), the lobbying group, was said to have advised that tougher standards could lead to “economic consequences for the building industry and the UK as a whole”.

Ms Barwise also referred to a fire at The Edge – a serious blaze at an apartment complex in central Manchester in 2005.

This fire spread via ‘sandwich panels’ and allegedly resulted in an investigator remarking that it “signalled the end of rainscreen cladding”.

But the Class 0 standard was still not removed, despite many EU member states introducing tougher European Euroclass standards.

Ms Barwise described this as “cynical” and said the reason the government may have been reluctant to remove it was research suggesting tougher European standards may “discriminate against” foil-faced insulation products, such as those made by Kingspan and Celotex.

She said Kingspan had “boasted” in a technical bulletin in 2003 that “government has stated that it will not implement the new Euroclass system until the industry is ready to adopt it”.

Ms Barwise singled senior civil servant Brian Martin out for particular criticism, saying he had responsibility for fire safety guidance Approved Document B for 20 years by the time of the Grenfell Tower fire and had described it as “almost like my third child”.

“His perceived superior knowledge of Approved Document B and fire safety rendered him untouchable, and his behaviour and that of his department with him, became puerile and callous,” she said.

When the coalition government came to power in 2010, Ms Barwise said a policy was adopted which showed “unwavering commitment to the housing construction sector even when it became clear it posed a threat to safety”.

Amid a drive to reduce regulation with a ‘one in, two out’ rule and a ‘red tape challenge’, a special waiver had to be obtained to make any changes to the Building Regulations, which had to be compensated in cuts to other regulations covering the sector.

Ms Barwise said the government considered whether this policy risked breaching human rights laws covering the right to life, but still did not act.

“Government’s recognition that its self-inflicted regulatory paralysis risked breaching the right to life, and yet continued with inaction in relation to building regulations, is chilling,” she said.

This focus on deregulation, she said, meant its efforts to respond to the Lakanal House fire “conflicted with its true priority” of deregulating the building sector.

She said that a report into the fire by Sir Ken Knight, the government’s chief fire and rescue advisor, focused on the failures of internal compartmentation despite him knowing that combustible panels on the external walls were sub-standard.

The DCLG (now rebranded) was said to have refused to make this information about the panels public, in order to “avoid giving the impression that we believe all buildings of this construction is inherently unsafe”.

She said the investigation was then “shut down” by officials, which she called “an extraordinary suppression of information” and a “grotesque abdication of responsibility” that “raises the spectre of a deliberate cover-up”.

This was compounded by the BRE’s report into Lakanal, which “failed to investigate downward spread or establish what the cladding panel actually was”.

She described the BRE as a “wholly flawed organisation” which had “presided over a series of inadequate and dangerously misleading fire investigations”.

She said “nothing meaningful” was done in response to the coroner’s recommendations, which included encouragement to fit sprinklers in social housing and a review of building guidance “with particular regard to external fire spread”.

Ms Barwise said this failure was deliberate. “The department’s suppression of the critical information as to the nature of the cladding removes the possibility of accident,” she said.

Mr Mansfield showed a document to the inquiry which revealed Mr Martin advised then minister Stephen Williams against meeting with an All-Party Parliamentary Group pushing for the Lakanal findings to be implemented.

Ms Barwise said that, in May 2017, another civil servant warned Bob Ledsome, deputy director of building regulations at the DCLG at the time, “we, or ministers, are increasingly vulnerable to some or all of these risks becoming material and [government] being held to account for being inactive”.

On the day of the Grenfell Tower fire, Sally Randall, then head of social housing at DCLG, wrote in an internal email: “Some of the stuff about disproportionate burdens feels uncomfortable today.”

Mr Mansfield added that Melanie Dawes, a senior civil servant in the DCLG, said in her witness statement that the day of the fire was the “first time she had heard of Lakanal House”.

“She’s telling the truth. She didn’t know. Why? Because Lakanal did not matter,” said Mr Mansfield. “All the recommendations, even the deaths had not spurred them into action, instead of misrepresentation.”

“Grenfell is a lens through which to see how we are governed. The failures are systems failures,” said Ms Barwise.

“These are both government and industry failures, as the former shrugs off responsibility onto industry and industry defaults to what suits it best.”

In his opening address, Richard Millett QC, counsel to the inquiry, said the investigation into the government will address four questions:

- Were the risks from high-rise buildings understood before the Grenfell Tower fire?

- Had lessons been learned from other fires in the UK and overseas?

- What steps had and had not been taken to address the risk from high-rise buildings?

- What motivated government in the approach it did take?

He also criticised some of the public bodies involved for lacking candour in their opening statements. “This inquiry is not a game of cat and mouse where core participants might hope that their witnesses will smuggle something past counsel to the inquiry,” he said.

“It is in the interest of the inquiry’s work and so in the public interest that these bodies fully embrace their obligations of candour and openness and face up to the stark realities that they reveal. Their written submissions tend to suggest that they have been drafted with fingers crossed.”

The inquiry will hear openings from the BRE, the National House Building Council and the government tomorrow.

Sign up for our weekly Grenfell Inquiry newsletter

Each week we send out a newsletter rounding up the key news from the Grenfell Inquiry, along with the headlines from the week

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters