You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Jules Birch

Jules BirchHousing inequality is rising not just between generations, but within generations too

Jules Birch scrutinises today’s Institute for Fiscal Studies report into declining of homeownership

Housing is so often presented as a story of inequality between the generations but what about inequality within generations?

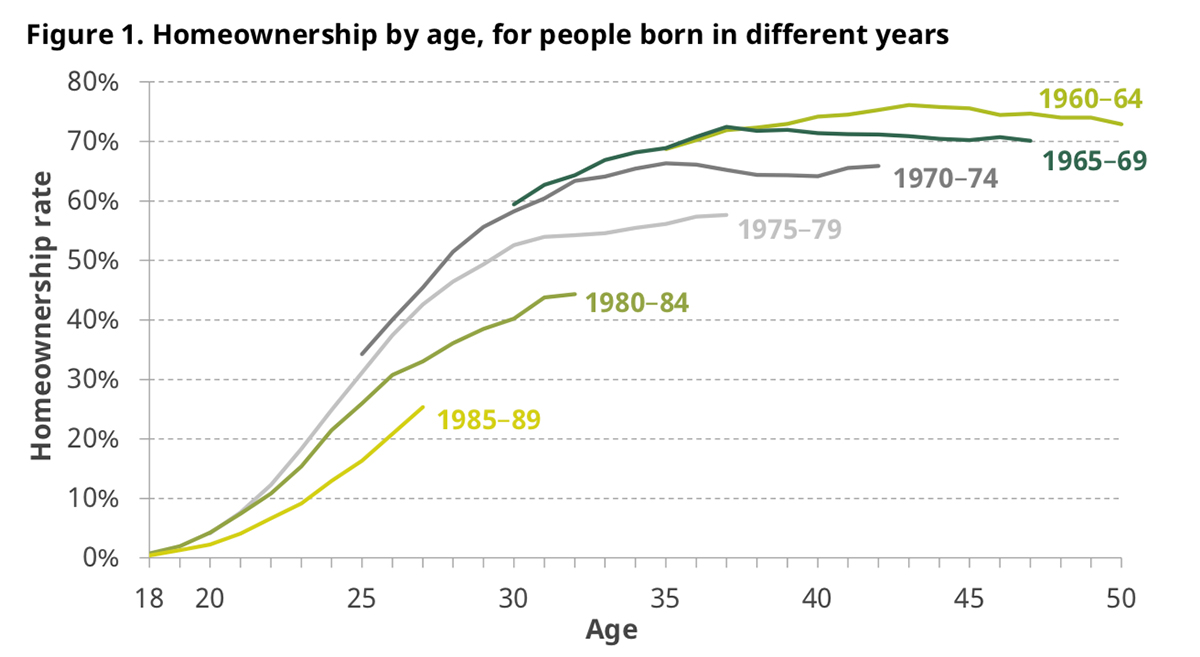

Analysis published on Friday by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) confirms the familiar story of the collapse of homeownership among younger people that has been accompanied by a surge in private renting and adults still living with their parents into their late 20s and early 30s.

The IFS briefing concentrates on people aged 25-34, exactly the age group who could once have been expecting to take their first step on to the housing ladder.

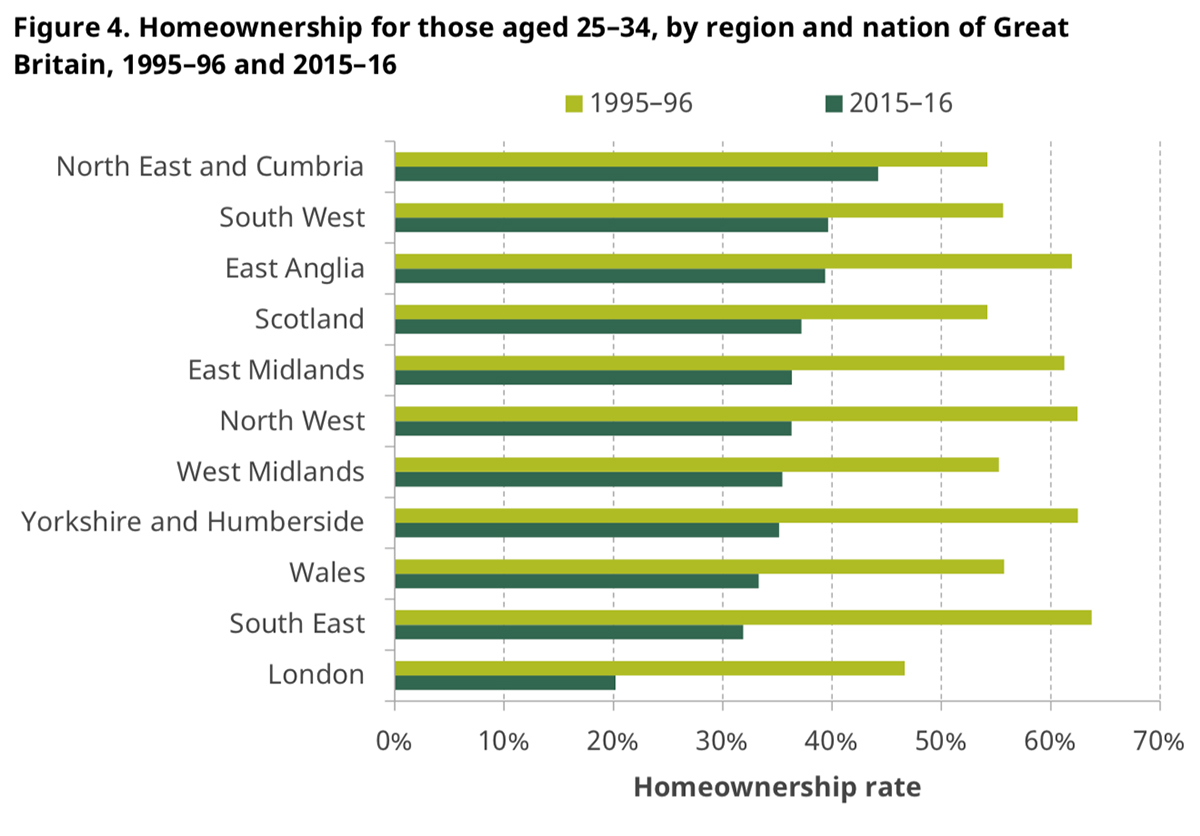

The collapse has obviously been biggest in London but homeownership rates have fallen even in the cheapest regions like the North East and Cumbria.

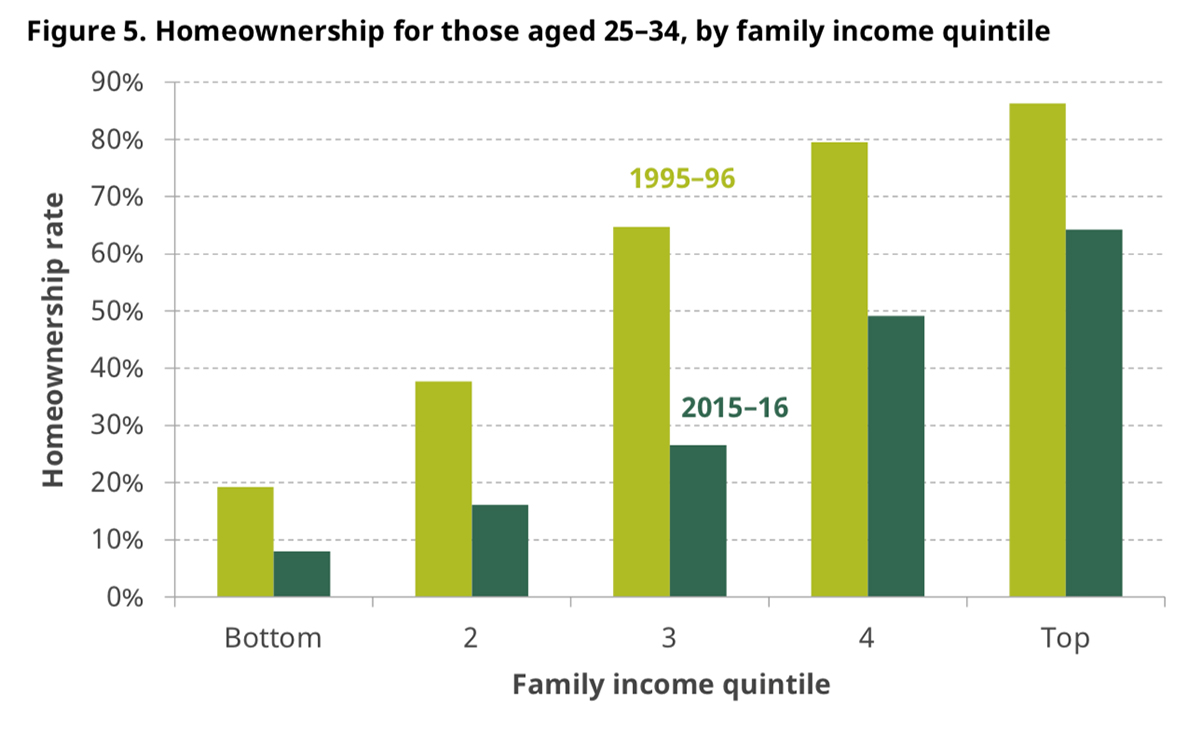

But the story within the story is what has happened within that 25-34 age group.

Broken down by income quintile, again the fall in ownership has happened across the board, even among the highest 20% of earners.

The biggest reduction (the one that makes most of this morning’s headlines) is the fall among the middle 20%: homeownership among people with after-tax family incomes of £17,900 to £24,900 has fallen from 65% to just 27% in the past 20 years.

By contrast, the highest earners (net family incomes above £41,100) saw the smallest proportionate fall (86% to 64%).

This graph shows all that but look at the collapse in ownership among the lowest earners, too:

That last point is borne out by the IFS’s analysis of what’s happened to slightly older people.

Among 35-44 year olds, ownership rates have fallen fastest among the lowest-income 20%, from 42% to 20% in the past 20 years.

The reason this is happening is that houses cost too much: the IFS finds that average house prices have risen 152% in the past 20 years while net family incomes of 25-34s have risen just 22%.

That point applies whatever measure of incomes and house prices is used and, for all the extreme consequences in London, it applies across regions.

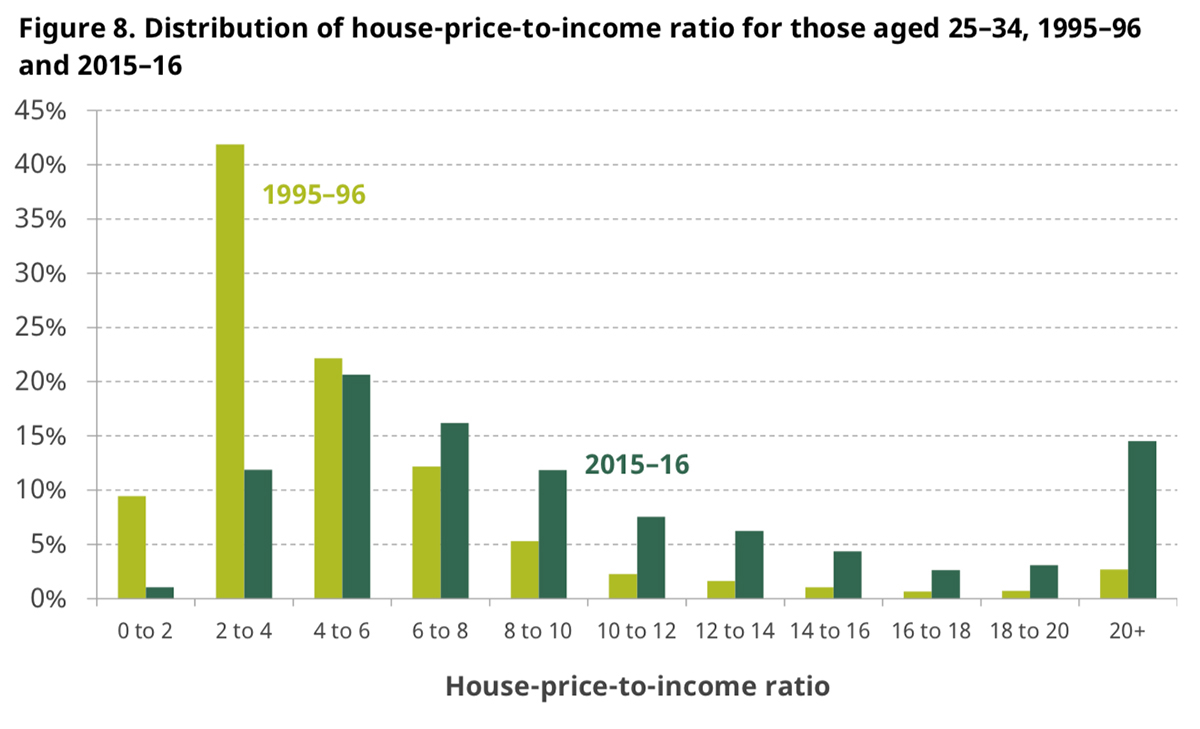

It is shown most dramatically in this graph showing the change in house price to income ratios for 25-34s: the biggest collapse has come in precisely the sort of homes that would once have been bought on a traditional income of three times income.

The IFS also investigates other influences on ownership prospects.

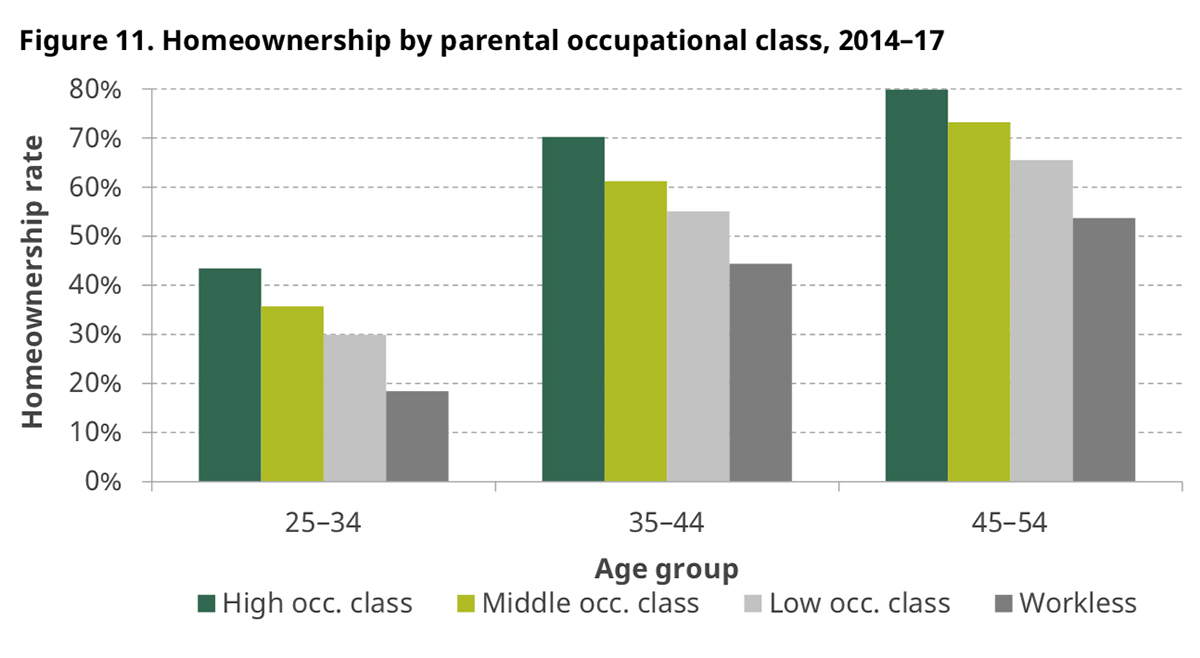

Broken down by the social class of their parents, there is a significant difference in ownership rates between those with mums and dads in jobs in the high (professional), middle (administrative and skilled) and low occupation class (unskilled) and who were workless.

The ownership gap applies not just to 25-34s but also to the 35-44s and 45-54s.

However, much of the difference disappears once the different characteristics (earnings, qualifications etc) of the young adults themselves are accounted for.

The IFS concludes that one reason for the remaining gap could be that parents in the higher occupational classes are more able to help their kids with a deposit while another could be inherited preferences about owning a home.

Combine those factors with the fact that people on lower incomes have experienced much bigger falls in ownership than higher earners and no wonder social mobility has stalled.

“The decline in ownership rates has come despite increasingly desperate measures from worried ministers and record low mortgage rates.”

In the 20th century, increases in homeownership among middle and low-income households were a key reason for declining inequality. In the 21st century that has gone into reverse.

The decline in ownership rates has come despite increasingly desperate measures from worried ministers and record low mortgage rates.

There are some hopeful signs for the youngest households and on some measures house prices are now falling in real terms which should make them more affordable over time.

However, it would take a sustained fall in prices in relation to earnings to start to send these trends into reverse.

And that could in turn expose a proportion of those who have succeeded in buying by stretching themselves to the limit.

Another report out this week looks at the most likely trigger for that: an economic shock from rising interest rates.

“Debt distress is most widespread among the poorest households, exactly the people most likely to be in private renting or social housing.”

The Resolution Foundation concludes that 6% of working-age households (1.2 million) are already in ‘debt distress’ and struggling to pay for their accommodation while another 17% (3.4 million) are very concerned about their level of debt.

Unsurprisingly, debt distress is most widespread among the poorest households, exactly the people most likely to be in private renting or social housing.

If interest rates rise, the biggest impact will be on the most indebted households who are buying with a mortgage.

The Resolution Foundation identifies 1.1 million ‘mortgage prisoners’, people who are unable to remortgage and will be trapped on their lender’s standard variable rate, plus another 810,000 ‘potential prisoners’ who have little equity in their home to remortgage with or would struggle to meet new income verification rules.

Jules Birch, award-winning blogger