You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Food for thought

This man is homeless and hungry so should organisations be allowed to give him food on the streets? Heather Spurr examines a debate which is once again under the spotlight

When Randeep Lall witnessed a homeless man threatening to throw a glass bottle at his volunteers, who were handing out free samosas to rough sleepers beside Charing Cross police station last autumn, he realised he had to make some changes.

Although the Sikh Welfare & Awareness Team had been travelling from Hounslow, in west London, to the centre of the capital to give free food to homeless people since 2009, the group had no protocol in place to deal with abusive customers, many of whom have alcohol and mental health problems. Since then, Mr Lall has sent his volunteers on training programmes and four workers now form a response team to tackle people in the queue for food who pose a risk.

Sikh Welfare & Awareness Team is one of many similar organisations that have made moves to tackle criticisms from councils and larger homelessness charities that their work serving food to homeless people on the streets is attracting crime, drug taking and litter. On top of this, soup runs, and in some cases, soup kitchens, have also been accused of enabling people to remain living on the streets and not engage with the services that can help to re-house them.

Last week Inside Housing revealed Camden Council flagged concerns at a meeting of the London mayor’s rough sleeping group about the ‘unintended consequences’ of the policy of sandwich chain Pret A Manger to give leftover food from its stores to homeless people. Pret A Manger vowed to keep providing food to ‘people who really need it’. Since then, the Greater London Authority has confirmed it has no plans to run a campaign asking retailers to stop donating food to homeless people.

But at least two homelessness charities currently face action by London boroughs wanting to move their soup runs out of their town centres. As a result, debate continues over whether organisations should provide handouts to people on the streets or supply food only to hostels where people can access services and support.

With the number of rough sleepers in the capital rising by 13 per cent to 6,437 between 2011/12 and 2012/13, should organisations that provide food be pressured off the streets and into indoor sites?

Negative impact

Jeremy Swain, chief executive of homelessness charity Thames Reach, has long campaigned against outdoor soup runs. He points to the fact that there are at least 30 soup runs on the Strand, a small strip of central London, per month.

‘Soup runs gathering regularly and en masse at particular locations can have a negative impact on local communities and businesses,’ he argues.

A key point to address at the outset is the difference between soup runs and soup kitchens. Soup runs provide food outdoors and are the main targets of local authorities because of the litter and anti-social behaviour that councils claim occurs as a consequence of their activity.

Jad Adams, chair of Croydon Nightwatch, is under extreme pressure from Croydon Council to move the charity’s soup run and its 100 volunteers from the town centre because the police allege it is a hotspot for crime.

‘[Police] claim people going to and going away from our site might be exhibiting anti-social behaviour but we haven’t seen any evidence of that and they haven’t presented any,’ Mr Adams says.

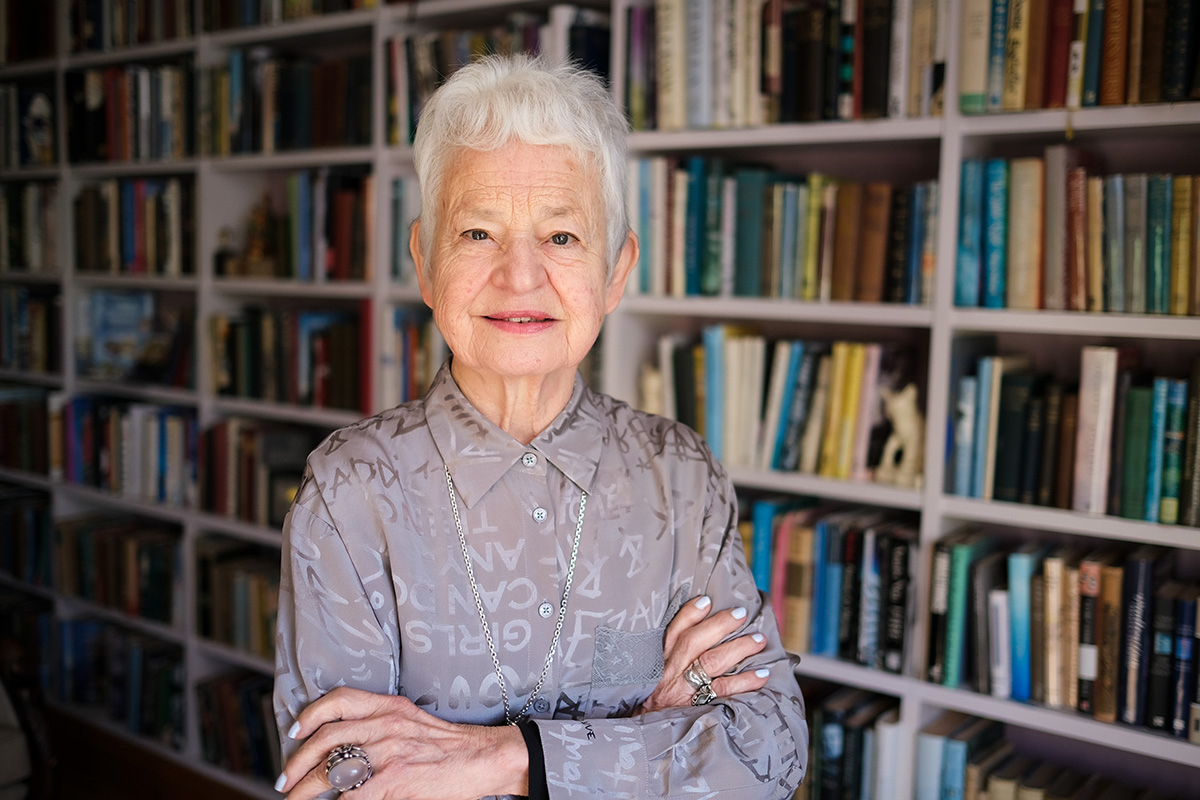

Source: Rex / Evening Standard

Volunteers from charity Sikh Welfare and Awareness Team feed homeless people in Southall, west London

Christian Kitchen, which operates a soup run in a Walthamstow car park in east London, is taking Waltham Forest Council to judicial review after the local authority said it would move it from its site in the town centre because it is a ‘magnet’ for trouble. But a freedom of information request last year revealed the council had received no direct complaints about the soup run in the preceding 12 months.

Then there are the soup kitchens, which provide food indoors, often in hostels. These are favoured by councils because the crowds are easier to control, there is less litter and homeless people can access and be directed to support services. Yet even then, there are tensions.

The main concern for large homelessness charities like Thames Reach, Homeless Link and St Mungo’s is not anti-social behaviour or litter but that soup runs do not link people to local homelessness support services. These large, professional homelessness charities with government contracts to get people off the streets argue rough sleeping leads to a spiral of addiction, alcohol and declining mental health. Their stance can be contrasted to small, often faith-based organisations, some of which argue there will always be people who choose to sleep rough and charities should serve food to them all.

Mike McCall, executive operations director at St Mungo’s, says: ‘While we understand the importance of providing food to homeless people, it remains our opinion that soup runs, rather than offering a solution to street homelessness, exacerbate and prolong [homelessness].’

Mark McPherson, director of good practice at umbrella body Homeless Link, says the longer someone sleeps on the streets ‘the worse their problems will become’.

‘Limiting support to just offering food can be problematic if it encourages someone to stay on the streets,’ he adds.

Many soup runs claim the problems of anti-social behaviour and litter stem from the sheer numbers of charities flocking to central London’s streets to provide food to homeless people and have become more organised to counter this. Housing Justice has drawn up a timetable listing which soup runs are operating in London at any given time so charities handing out food don’t double up.

Alison Gelder, the charity’s director, says some London soup runs have gone indoors to become soup kitchens and now serve food out of King George’s hostel in Victoria.

‘Everyone would prefer it if [homelessness organisations] could provide food indoors,’ she says.

But not all charities agree every soup run should be abandoned in favour of soup kitchens, nor even that charities should be the ones to connect homeless people to local services.

Unconditional support

Mr Lall says the Sikh Welfare & Awareness Team signposts people to support services - but only if they want to engage. ‘There’s no point talking to someone if they don’t want to talk to you,’ he says. He would rather feed people without making food conditional on receiving support.

Donald Ewers, manager of the Good Samaria Network, moved from serving food and tea outside Temple underground station to St George’s hostel in 2004. But he insists a ‘blanket policy’ of abandoning soup runs for soup kitchens should not be applied.

‘No one stays on the streets for a cup of tea,’ he says. Some rough sleepers want to remain ‘under the radar’, he adds. Illegal immigrants, for example, might fear a homelessness charity asking for identifying information.

Data from the GLA-funded Combined Homelessness and Information Network shows that just 47 per cent of the 6,259 rough sleepers in 2012/13 were from the UK. The problem is that some of these foreign nationals have no recourse to public funds. Consequently they cannot receive housing benefit to pay hostel rent.

‘[Many] hostels [therefore] refuse people who don’t have access to public funds,’ Croydon Nightwatch’s Mr Adams says. The number of hostel spaces has also decreased by 4,000 since the last election, so it is easy to see why soup run providers smile bleakly when you suggest their services should signpost rough sleepers to hostels.

Additionally, although many agree that giving out food in the cold winter weather is preferable indoors, there is currently no fund from the GLA or the Communities and Local Government department to open more indoor soup kitchen spaces. Getting accommodation in which to operate is proving difficult for charities as residents and businesses can be unwilling to grant planning applications that will result in more homeless people in their areas. It is also a difficult task to persuade day shelters to open for extra hours in the evening, Ms Gelder says.

Councils have had some successes in removing outdoor soup runs. Soup runs outside Westminster Cathedral no longer congregate in large numbers according to Mr Swain after discussions between Westminster Council and charities. But it is difficult to see all of the soup runs packing up unless they are forced to do so and any decision to force soup runs off central London’s crowded streets is likely to be a public relations nightmare.

As for Mr Lall, he is adamant no one will stop his volunteer group serving food outdoors: ‘They [the police] are going to have to start nicking us stop us feeding homeless people,’ he says.

Feeding homeless London

Area: Victoria

Number of soup runs: 11

Area: West End

Number of soup runs: 10

Area: Strand, Embankment, Temple, Waterloo

Number of soup runs: 55

Area: Lincoln’s Inn Fields

Number of soup runs: 26

Area: King’s Cross, Camden, Kentish Town

Number of soup runs: 18

Area: Other

Number of soup runs: 37