You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Jules Birch

Jules BirchTheresa May and Old Joe

Jules Birch draws parallels between the Conservatives’ housing plans and 19th century politician Joseph Chamberlain

Jules Birch

Jules BirchEver since the advance reports of what would be in the Conservative manifesto, I’ve been wondering where the party’s new housing agenda comes from.

As I blogged at the time, the manifesto programme seems to go well beyond the Housing White Paper. It involves not just “a new generation of social housing” but also enhanced compulsory purchase powers for councils and land value capture.

The obvious answer – one that all governing parties do in their manifesto – is to take what is already on the stocks in the relevant department and spin it into a more visionary-sounding idea.

That seems to be what happened with the discussions already under way between the Department for Communities and Local Government and three councils – Stoke, Sheffield, and Newark and Sheffield – about a package of measures that would enable them to build more homes.

As Inside Housing reported last month, the deals with those pilot authorities involve not just flexibility on borrowing caps but potentially new deals on rents and land assembly too.

That is important because councils have identified a range of barriers to them building new homes, including the caps, the way Right to Buy receipts are treated and (especially) the rent cut. Funding would come from the £1.4bn allocated in the Autumn Statement.

“The use of ‘municipal’ is a throwback to an earlier era of council housing.”

But the manifesto seems to be about more than just a few pilots and some existing money. Limited new freedoms piloted in some authorities, perhaps allowing something more like the original idea for self-financing (before the rent cut scuppered so many new build plans) would be very welcome, but they would hardly qualify as a new generation of social housing (even though it remains unclear whether that means social or affordable rent).

And while the Conservatives under Theresa May had already moved away from the obsession with homeownership seen under David Cameron, this seems to go further.

But where else does it come from? Look first at the language used in the key line of the manifesto in which the Conservatives admit that the market alone cannot deliver: “We will never achieve the numbers of new houses we require without the active participation of social and municipal [my emphasis] housing providers.”

The use of ‘municipal’ is a throwback to an earlier era of council housing and I think this is not a coincidence.

Because, next, look at who wrote the manifesto. Nick Timothy, Ms May’s joint chief of staff, is generally thought to be behind the rhetoric about “ordinary working-class families”. He was brought up in Birmingham and five years ago published a biography of his political hero, Joseph Chamberlain.

‘Old Joe’ was the reforming mayor of the city in the 1870s and founder of a political dynasty that includes his sons Austen and Neville.

He was a contradictory and divisive figure, a radical who became a reactionary and managed to split two political parties. Originally a Liberal, he left over Irish Home Rule to become a Liberal Unionist allied with the Conservatives, only to fall out with them over tariff reform.

His influence is plain from the use of the full Tory name on the front of the manifesto (the Conservative and Unionist Party, where in 2015 it was just the Conservative Party) as well as in the party’s new interest in the working classes.

Next, look at what follows the bit about social housing in the manifesto: “We will reform compulsory purchase orders to make them easier and less expensive for councils to use and to make it easier to determine the true market value of sites.”

In part this reflects a growing interest in compulsory purchase and land value capture across the political spectrum. The bit that follows about “making it both easier and more certain that public sector landowners, and communities themselves, benefit from the increase in land value from urban regeneration and development” does take up hints in the Housing White Paper about borrowing ideas from continental Europe.

However, it is also a throwback to what Joseph Chamberlain did in Birmingham and to political debates of the 19th century.

Mr Chamberlain was in many ways the original metro mayor. He believed in local government run on business lines in the service of the community, which meant municipalisation (buying local private utilities like gas and water) and improvement (temporary intervention to correct market abuses like slum housing and threats to public health).

His Birmingham Improvement Scheme used new compulsory purchase powers to buy up areas of slum housing for clearance and reconstruction in the 1870s. Walk down Corporation Street today and you can see the results.

The line from the manifesto about making it “easier to determine the true market value of sites” directly recalls the arguments made by Mr Chamberlain and other land reformers about only paying the “fair market value”. By this he meant the price a willing seller could get on open market, with no allowance for the compulsory purchase and its value after that.

"Joseph Chamberlain was in many ways the original metro mayor."

However, Mr Chamberlain’s radicalism had strict limits. The Birmingham Improvement Scheme resulted in the demolition of 900 homes. These were slums but they also had the cheapest rents in the city. Nine years later, no replacement working class homes had been built.

Mr Chamberlain later argued in government that local authorities should not build homes because that would stop private builders constructing working class dwellings. In the 1880s he supported an exception for London but later opposed this, arguing that local government should demolish slums and leave housebuilding to the private sector.

Next, think about the manifesto’s key caveat on the new social housing: “We will build new fixed-term social houses, which will be sold privately after 10 to 15 years with an automatic Right to Buy for tenants, the proceeds of which will be recycled into further homes.”

Where does this come from? After all, the 10 to 15-year fixed term seems to directly contradict the current three-year qualifying period for the Right to Buy and the government’s existing plans for fixed-term tenancies with five-yearly reviews.

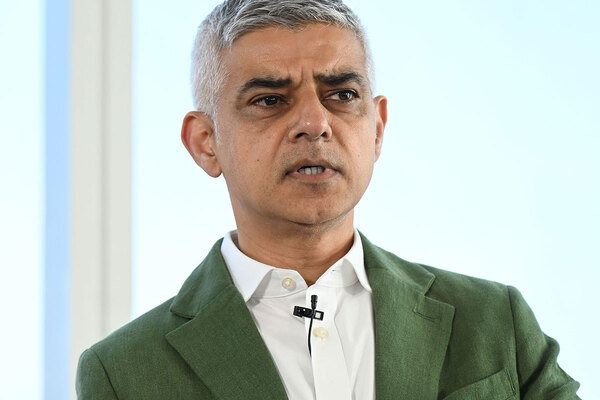

One contemporary answer might be Sadiq Khan’s London Living Rent programme. As originally planned this was an intermediate rent scheme for middle income tenants and this seems to be part of the affordable housing programme that Labour is planning nationally if it wins the election next week.

However, as amended after discussions with the Conservative government, it seems to have become a rent-to-buy scheme with a five-year tenancy followed by purchase.

Another answer might be covenants on build-to-rent sites requiring a proportion of homes to be let on discounted rents for 10 to 15 years. But by definition the affordable private rent homes mentioned in the Housing White Paper are not social housing.

So I’d suggest that part of the answer again harks back to the 19th century. Despite Chamberlain’s opposition, in 1890 the Housing of the Working Classes Act gave the new London County Council the power to build homes for the first time and this was later extended to the rest of the country.

But under two parts of the act, local authorities were compelled to dispose of any homes they built after 10 years unless they were given power to retain them. Sound familiar?

There was also no subsidy available until after the First World War. That meant not just high rents but also a reluctance to build among many local authorities because ratepayers would take all of the risk. Only 25,000 council homes were built by 1914.

And here’s where contemporary and historical debates about how to house the working classes seem to meet: a gradual acceptance that the market alone cannot deliver followed by a slow realisation of what that means.

As the Conservatives mix 21st century housing solutions with ones from the 19th century, perhaps it might be worth thinking about what happened in between.