You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

EWS: Why the attempt to fix the cladding and mortgage crisis is not working

The EWS form aimed at solving the cladding and mortgage crisis has not had the desired impact. Jack Simpson finds out why flat owners are still trapped. Picture by Alamy

Leaseholders in 15m-high Adelaide Wharf in London (above) are now embroiled in the cladding crisis

When then-housing secretary James Brokenshire announced a ban on combustible materials in new high rises in 2018, little did he know the effect it would have on sales across the country.

The implication for new build was clear enough, but the more difficult question was: what did it mean for the tens of thousands of blocks around the country which have already been built and contain combustible materials in their walls?

Within weeks, ‘Advice Note 14’ was published, the official government note that told building owners to check cladding systems and carry out work to make them safe if necessary.

Early last year, the implications of this began to appear. A trickle of flat owners trying to sell reported being denied a mortgage unless they could provide an official test result declaring their block safe. This trickle soon became a flood and reached crisis point last autumn – with flat sales almost grinding to a halt nationwide and thousands of lives put on hold.

Hundreds of apartments bought just a few years earlier for vast sums were now being given £0 valuations. Mortgage providers followed, with many unwilling to lend on these properties due to cladding concerns. A solution was needed.

After months of discussions, in December, organisations led by the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) and banking industry trade body UK Finance created the ‘External Wall System 1’ form, a review process which has become known as EWS.

Hailed as a way of “unclogging the property market”, it was hoped it would allow it to “function properly again”.

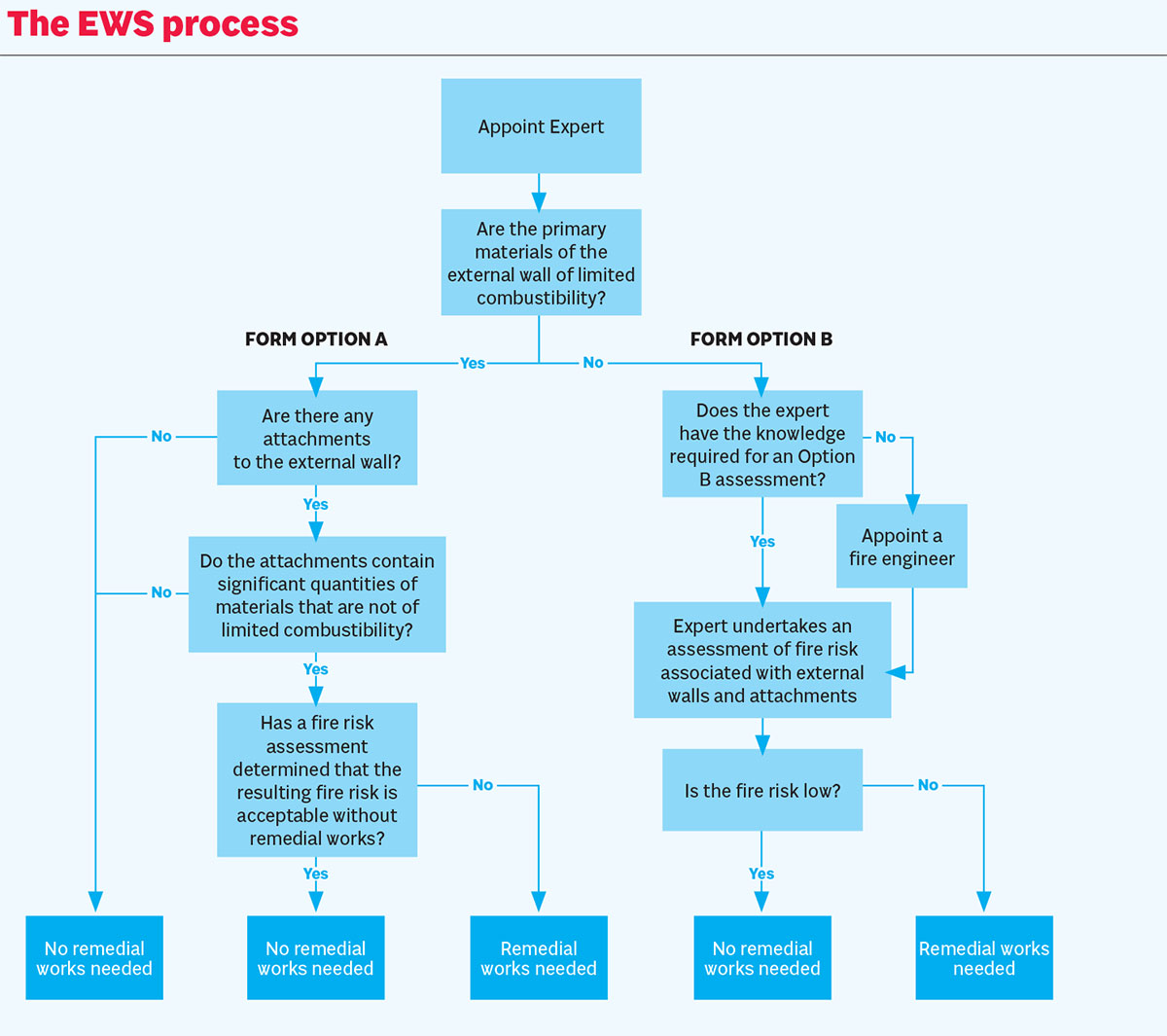

At its heart, the EWS process was moving away from the binary approach of Advice Note 14, which states that external walls on all buildings over 18m must be checked and if materials were combustible they must pass a large-scale test.

The EWS process is more nuanced and allows a “competent chartered professional with fire expertise” to check materials and give assurances to lenders that it is safe or in need of remediation.

The expert must first assess whether materials of limited combustibility are present. If they are present, it is given a clean bill of health for mortgage companies. If the materials are found to be combustible, but a fire risk assessment deems the risk to be low, it is also given the green light for lenders. The guarantee lasts for five years.

If an external wall is found to have combustible materials, then a chartered fire engineer must be appointed to carry out a more in-depth assessment.

If they deem the fire risk to be low then lenders are again given assurances. If deemed high risk, remediation work is then needed (see flowchart below).

“After Grenfell there was clear advice that buildings needed to be checked; the EWS process enables those checks, which can also be used by lenders and valuers for the valuation process,” explains John Baguley, tangible assets valuation director at RICS.

But securing an inspection is the first hurdle and it is not simple or quick for leaseholders. With records over materials used in construction severely lacking, or non-existent for many buildings, intrusive checks are needed in the majority of cases to establish what is actually on the walls. The pool of experts available to carry out these checks is small. This pool gets even smaller because liability concerns have scared many away.

Rendall & Rittner, one of the country’s largest property managers, said, for example, there is a very limited number of qualified experts available to carry out the checks and this was leading to delays.

This is exacerbated by an insurance crisis in the sector, with many inspectors unable to obtain professional indemnity (PI) insurance for the checks. PI insurance covers construction professionals from negligence claims but has been made increasingly difficult to secure post Grenfell, as insurers run scared of the potentially enormous payouts that would result from another big fire.

Inside Housing has seen correspondence between one large London housing association and a shared owner, which describes the situation as at a “deadlock”.

Even once an inspection is carried out, it is unlikely a leaseholder’s building will get a clean bill of health.

While the EWS form offers five potential outcomes, the most likely route remains that inspectors will determine remedial work is required. This is simply a result of the vast number of buildings that have combustible materials of some kind on their walls.

One source told Inside Housing that he had heard of a surveyor who saw 34 of the 35 EWS forms completed conclude that remediation was needed. And with the pace of remediation work glacial, this could mean a delay of many years before a sale goes ahead. The leaseholder could also very likely find themselves footing the bill for the work.

Despite these issues, the EWS system is working for some buildings, Mr Baguley claims. “I’ve heard of examples of buildings that don’t have combustible materials, which have been confirmed by the EWS process, and sales on those blocks are now going through,” he says.

However, it is clear the property market is far from “functioning properly” as had been hoped. For those that have completed the EWS process, there is still no guarantee that banks will lend.

Despite UK Finance backing the process, some banks are still reluctant to agree mortgages even after the EWS process has been completed. Inside Housing understands that a handful of banks are now accepting EWS forms but other major banks are not – creating inconsistency and confusion.

A leaseholder in Leeds who completed an EWS inspection which deemed her building to be low risk has been unable to secure a mortgage from Halifax. And this is an issue for newer buildings, too.

“I’ve heard of examples of buildings that don’t have combustible materials, which have been confirmed by the EWS process, and sales on those blocks are now going through”

Charis Beverton, senior associate at Winckworth Sherwood, says that not all lenders are accepting EWS forms, with some even requiring apartment-by-apartment checks. She adds: “This is an acute issue for newly constructed buildings and those in construction where developers, contractors and employers were trying to meet fluctuating demands from regulators and lenders.”

Jamie Ratcliff, executive director of business performance and partnerships at Network Homes, says the take-up by lenders has been slower than expected.

“There is a lot of work that has gone into this, and there is a lot of bedding in for banks,” he says. “Some have adopted and some are in the process of adopting but haven’t yet, which I appreciate is of little comfort to those suffering currently.”

There are now fears that new government guidance could bring more leaseholders into the cladding scandal.

The EWS form

The government’s consolidated guidance, which replaced Advice Note 14 in January, calls for EWS-style checks on all buildings regardless of height.

As a result, buildings as low as 9m are understood to be impacted. If this continues it could leave flats in hundreds of thousands of buildings unsellable – with millions affected.

Mr Baguley says while the EWS form was created for buildings of 18m or above, it says blocks with “specific concerns” should also be checked. He adds that RICS will be putting out separate advice on buildings under 18m very soon.

But whether above or below 18m, the mortgage issue is growing.

Mr Ratcliff says EWS was only ever going to be a “sticking plaster and would never solve the problem in its entirety”.

He says that while it is unlikely the government will draw up a blank cheque to fix issues, it could create an insurance system for leaseholders.

“The government could potentially underwrite an insurance product at the point of sale, which could see the buyer pay a fee and if works are required the insurance will pay for it,” he says. He adds that if priced correctly it could minimise government exposure.

Dr Jonathan Evans, chief executive of cladding firm Ash & Lacy, suggests a new route should be created by government to certify the findings of an EWS form for mortgage lenders, with this being supported by a centralised team at the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government that could quickly classify cladding samples.

He added: “A new EWS form should ideally be accompanied by further guidance for inspectors, such as a matrix of materials and their risk.

“At the moment we are relying on people’s experience and seeing inconsistencies as a result.”

Whatever the solution, one needs to be found soon. As people attempt to buy or remortgage their properties, more will realise just how trapped they are. And for the vast majority, the EWS process will not provide a route out.

Sign up for our weekly Grenfell Inquiry newsletter

Each week we send out a newsletter rounding up the key news from the Grenfell Inquiry, along with the headlines from the week

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters

Related stories