You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Fire safety tests of cladding examined

Luke Barratt takes a closer look at the cladding tests that have cast doubt on official fire safety findings

One hundred degrees hotter, four times longer and with a far greater risk of spreading: the flames that consumed cladding in independent fire safety tests are described in worrying terms, compared to official tests.

The insurers who commissioned the tests say they reveal the “utter inadequacy” of the existing test regime, so Inside Housing has decided to compare them directly to the various government-commissioned cladding tests that have been done since the Grenfell Tower fire to understand the differences.

In the aftermath of the fire that tore through Grenfell Tower and killed 72 people, the government commissioned seven large-scale tests from the Building Research Establishment (BRE), which would look at whether, despite failing those first tests, the materials used might be safe if combined with other, less combustible materials.

The tests, known as BS 8414 tests, and designed by the British Standards Institution (BSI), involved setting a fire at the base of a nine-metre model wall to see whether fire spread up the side.

As Inside Housing reported at the time, the Fire Protection Association (FPA) – the fire safety wing of the Association of British Insurers (ABI) – lacked confidence in the results of these tests.

On behalf of the ABI, it carried out a series of new cladding tests on six- metre high walls designed to be more realistic. The aim was to examine the adequacy of the BS 8414 test, looking at five key areas. It’s worth going through these in turn.

The first area of concern was the fuel load. A BS 8414 test sets fire to a crib made of wood at the base of its model wall. According to the FPA’s test report, however, 20% of the fuel for a flat fire is usually plastic-based.

"Aluminium loses integrity quickly when it heats up"

The FPA did two almost identical tests, except that one used a fuel load including 20% plastic. In the latter, flames were one metre longer and the temperature was 100 degrees hotter.

Aluminium, the report notes, loses integrity quickly when it heats up. A 100 degree difference in temperature caused by the presence of plastic could, the FPA concluded, cause tests done on aluminium to fail that might otherwise have passed.

The second area was vents and ducts. In a BS 8414 test, the cladding system is perfectly smooth and intact, without: windows, vents, ducts or pipes. This, of course, is not what a real wall is like, and the FPA suggested that such additions could make it easier for fire to spread.

This suggestion gained greater importance a couple of weeks ago, when a leaked report provided by the BRE to police investigating the Grenfell Tower fire – seen by Inside Housing – revealed that when the fire escaped from the flat where it started, the window frame provided “fuel” and there wasn’t “any substantial barrier to fire taking hold on the facade outside”.

When the FPA added a bathroom-type vent into the wall, flames spread into the cavity immediately. In fire safety, it is considered vital to avoid, as far as possible, fire spreading into the cavity of a cladding system, as this can lead to a ‘chimney effect’.

This chimney effect was the FPA’s third concern. Its report suggests that BS 8414 tests, in which edges are often sealed, are unrealistic.

"Cavity barriers could not expand quickly enough to block the spread of flame."

The association again compared two tests, one with cladding with sealed edges and one without seals. In the first, fire climbed 1.5 metres up the open face before burning out and self-extinguishing, as happened in the government’s passed tests.

When edges were not sealed, fire spread six metres, to the top of the model wall, four times further.

The fourth area of concern for the FPA was cavity barriers, designed to expand when they detect flame to stop it spreading.

In a BS 8414 test, barriers are heated from an early stage when flames touch the outside of the

system. If the cladding holds for long enough, they expand before fire gets into the cavity.

As the FPA has already shown, though, fire can spread into the cavity through other routes. When it simulated these means of spreading, it found that cavity barriers could not expand quickly enough to block the spread of flame.

The FPA’s fifth and final concern is perhaps its most concerning. Its report states: “There is concern that some testing has allowed significant reinforcement of the system with features that may benefit its ability to pass the test but might not be design features of end-use applications.”

To examine this, the FPA replicated one of the government’s tests and compared it to an identical system with what engineering firm Arup said was a “typical on-building design”.

The Paper Trail: The Failure of Building Regulations

Read our in-depth investigation into how building regulations have changed over time and how this may have contributed to the Grenfell Tower fire:

In the latter test, panels fell away from the wall and fire spread horizontally as well as vertically. These things were both seen to happen at the Grenfell Tower fire, but did not happen in any of the government’s BS 8414 tests.

The FPA has provided its report to the BSI, which will examine and decide whether it needs to review the BS 8414 standard.

Though many have responded with shock to the FPA’s findings, one leading fire safety expert is sceptical, telling Inside Housing: “I take their point that fire tests on external wall construction don’t always reflect reality, but I’m not sure what they’re trying to prove.

"Fire tests are a way of comparing one form of construction with another. At the end of the day, I’m not sure there’s any evidence that the BS 8414 test is broken.

“The FPA have their own agenda in trying to push their testing. I’m not entirely convinced. The thing I was slightly sympathetic to was the vents going through, because you can’t simulate that with a BS 8414. It’s occurred to us on several occasions, what about these vents going through the cavity? How do you allow for these? I’m not sure where that leaves us, to be honest.”

The BSI has said if the FPA’s findings and evidence are “technically feasible” then the two will work together to amend the standard.

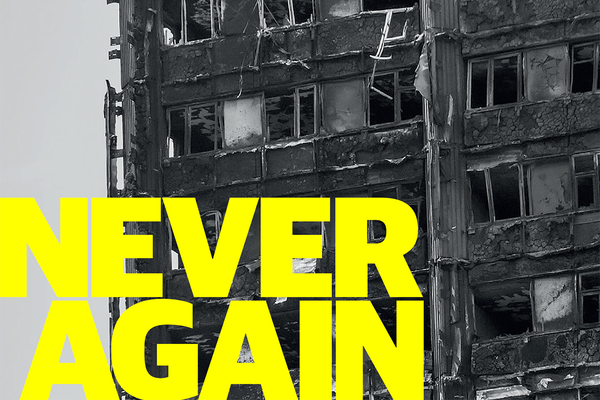

Never Again campaign

Inside Housing has launched a campaign to improve fire safety following the Grenfell Tower fire

Never Again: campaign asks

Inside Housing is calling for immediate action to implement the learning from the Lakanal House fire, and a commitment to act – without delay – on learning from the Grenfell Tower tragedy as it becomes available.

LANDLORDS

- Take immediate action to check cladding and external panels on tower blocks and take prompt, appropriate action to remedy any problems

- Update risk assessments using an appropriate, qualified expert.

- Commit to renewing assessments annually and after major repair or cladding work is carried out

- Review and update evacuation policies and ‘stay put’ advice in light of risk assessments, and communicate clearly to residents

GOVERNMENT

- Provide urgent advice on the installation and upkeep of external insulation

- Update and clarify building regulations immediately – with a commitment to update if additional learning emerges at a later date from the Grenfell inquiry

- Fund the retrofitting of sprinkler systems in all tower blocks across the UK (except where there are specific structural reasons not to do so)

We will submit evidence from our research to the Grenfell public inquiry.

The inquiry should look at why opportunities to implement learning that could have prevented the fire were missed, in order to ensure similar opportunities are acted on in the future.

What are desktop studies, and why are people concerned?

Building regulations say cladding systems which contain combustible insulation must be shown to meet specific standards based on “full scale test data”

A ‘desktop study’ is a means of making an assumption about whether or not a cladding system would meet these standards without actually testing it.

It involves using data from previous tests of the materials in different combinations to make assumptions about how it would perform in a test.

This is not specifically provided for in the current guide to building regulations, but the government believes they are loosely drafted to an extent which makes it permissible. It plans to redraft the guidance to include specific rules on the use of desktop studies for the first time.

The alternatives to a desktop study are full scale testing or not using combustible materials.

People are concerned about the process because it is based on assumption: at least one system cleared through a desktop study has failed a full scale test.

This is important for fire safety because mistakes may mean unsafe cladding systems being cleared for use on tall buildings.