Back to the future

Experiments in eco-housing are nothing new. Philippa Ward learns the lessons of designs from the 1970s, 80s and 90s

1970s

Wates low-energy house

Machynlleth, south Snowdonia, Wales

Trend setter Super-insulation

Could do better Use of natural light and ventilation

Deep in the Welsh countryside, in a disused slate quarry, is one of the first examples of a self-styled ‘eco-house’. Cheap energy and post-war building techniques meant that by the 1970s, buildings were leaking heat from every corner. The newly founded Centre for Alternative Technology asked the then Wates Built Homes house builder to build a demonstration house. The idea was to show what was possible in energy efficiency using existing technology, without building a wacky-looking, expensive house - not so different from challenges today.

Wates got the call in 1975, when CAT opened to the public. That was just two years after the eco-centre was set up by a group of idealists who wanted to test new ideas and technologies to help find a greener way of living. Volunteers worked long hours - sometimes by candlelight - to build habitable green dwellings. It was a far cry from today’s shiny research establishments.

CAT has modernised as well: now it hosts 65,000 visitors a year, including me, many of whom wander round the Wates house and learn from those early experiments. And as further proof of the building’s contemporary relevance, the visitor shop is still selling fact sheets about it for 50p.

My guide around the house is Peter Harper, head of research and innovation at CAT. He reckons I’m looking at ‘the most insulation in Britain’. It doesn’t seem likely that any heat could get through the two super-insulated walls: they are as thick as something you’d find in a medieval castle, longer than my arm. The brick walls have a cavity of 450mm between them, filled with glass fibre.

The walls are unwieldy; but they work. The u-values are six times higher than current building regulations require. At 0.075W/m2 they would qualify the house for level 6 of the code for sustainable homes. It was calculated that if a family was living there, no heating would be needed at all.

‘It worked with what was available at the time: air permeability was not really known about then,’ says Mr Harper. ‘This was very much the “bottle them up” route. Our builders and architects went down the passive house route.’ So not necessarily a place you would want to live in.

Looks aren’t everything

The windows are quadruple glazed. Continuing the medieval fortress theme, they are also small. An unfortunate side-effect of that is that the lights need to be kept on all day, which isn’t exactly green living. There was no use of passive solar gain here, which captures the sun’s heat to warm rooms - a technique that has since become mainstream.

Nor was there any attempt to make the house look appealing. The brief was to design a conventional house, so the public would not be prejudiced by its appearance. The roof is covered in concrete tiles and the whole thing is squat and heavy. Compared with the award-winning choice from the 1980s and the appealing earth-sheltered 1990s development, the Wates house loses out.

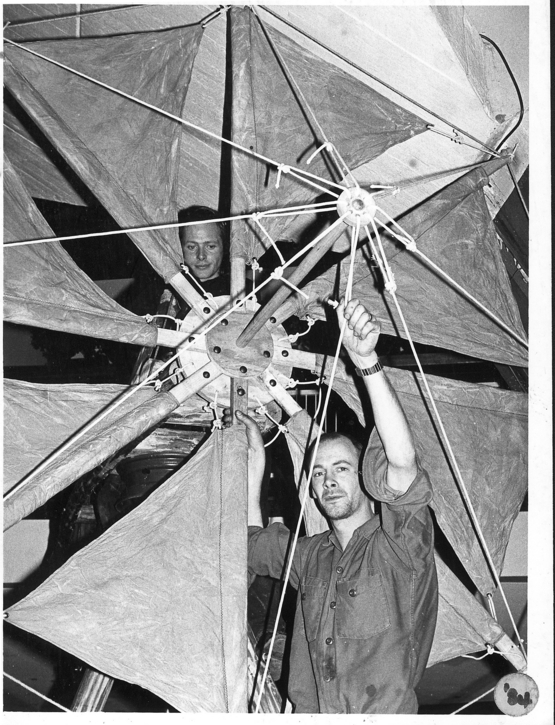

But it was a time of constant innovation. Originally, even the oven was super-insulated by surrounding it with 150mm of glass fibre. Later, a delightfully homemade system was added by which a 15Kw wind turbine charged up car batteries which could then power appliances. Waste heat was dumped in the Aga to be used for cooking.

The house has been put to a variety of uses - and we can learn from that today. It was built with a central core to carry service wires and make a warm central stem for the house. That means that its internal walls can be altered - for example, the upstairs is now used as offices and the staircase has been moved outside. A glass-walled extension has also been added to harness natural light and heat.

So even though it is now a demonstration house, the Wates home is still being used and it still works. Its energy use is astonishingly low - 950kWh compared with 13,000kWh for a conventional house in winter - despite being on a hill in deepest, rainiest Wales.

1980s

Spinney Gardens

Crystal Palace, south London

Trend setter Passive solar gain

Could do better Renewable energy

Spinney Gardens is a world away from the Wates House, despite being less than a decade younger. For a start, people live in the houses - and they like it, with many of the original tenants or their children still living there. The homes rely on design and orientation for their energy efficiency, rather than super-insulation.

The project was the winning entry in a Royal Institute of British Architects competition to provide affordable starter homes that were energy efficient. The link between low-cost housing and green living is now taken for granted - back in 1981 it was an unusual brief. The homes were designed by two young architects from Poland, Andrew Ogorlazek and Peter Chlapowski, who spent their evenings and weekends of the long hot summer of 1981 sweating over the plans in a garage. ‘Charles and Diana were getting married, and we went upstairs and had a break for a couple of hours to watch that - then back to it,’ remembers Mr Chlapowski, now a partner at PKCO, which he set up with Mr Ogorlazek after the competition.

Mr Chlapowski was studying low- energy design at Kingston Polytechnic, while Mr Ogorlazek’s PhD was on urban syntax - how people move around the space they inhabit. They brought these two elements together in their award-winning entry.

‘In the late 1970s and early 1980s, people started to get interested in energy but very few people were translating it to design,’ says Mr Chlapowski. ‘Then there was no legislation, nothing on u-values. We used manual calculations. But I’m sure not everyone was doing even that.’

The competition was run by Abbey Housing Association, set up by Abbey National Building Society. As with the Wates house, there were budget limitations, so the houses could go to first-time buyers.

But the site was anything but limited. ‘It was almost arcadian in feel, with vegetation everywhere, having been empty since the Crystal Palace fire [which destroyed the huge glass hall in 1936],’ explains Mr Chaplowski.

‘There was this fantastic nostalgic feel of the Victorian engineering, and the ghost of Crystal Palace not far from the site - we wanted to include that [in the designs].’

The houses, in south London, don’t look obviously ‘green’ - they are simply great examples of 1980s architecture, complete with warm red bricks and lots of gleaming glass.

They are also the first mainstream example of using passive solar gain to heat houses. Each of the timber framed buildings has a two-storey triangular conservatory attached to the south side, which captures energy from the sun and transfers it to a high-mass wall that acts as a heat store.

Inside, the dwellings are carefully planned to get maximum benefit from the sun and allow the heat and ventilation to flow through. The most used areas are on the south side of the building and there is minimal glazing on the north side.

As with the 1970s Wates house, there was post-occupation monitoring - 12 months of interviews, questionnaires and modelling studies. This estimated that bills were 30 per cent lower than for an equivalent standard house. Tenants say that they remain low today.

Another innovation was the guidebook that the architects produced, to help the inhabitants make the most of the buildings’ design.

The homes won an Energy Award in 1985 and a Housing Design Award in 1987. Last year the scheme was given a special Housing Design Historic Award, for its continued success as an energy-efficient and valued place to live.

1990s

Hockerton Housing Project

Southwell, Nottinghamshire

Trend setter Use of natural materials and sustainable lifestyles

Could do better Convincing the world

Hockerton was the UK’s first earth-sheltered housing project: it is insulated by 500 tons of earth on the walls and roof that wrap around it like a blanket. The aim was to be zero carbon, producing no net carbon dioxide emissions - a massive leap forward in ambition from the experiments of the 1970s and 1980s.

‘It was very ground-breaking - and it still is,’ says Simon Tilley, resident at Hockerton since the beginning. ‘The standards proposed now will catch up in eight years’ time. It is designed to have zero heating, which most developers don’t seem to think is possible.’

The emphasis was as much on sustainable lifestyles as the building fabric. The residents of the five houses generate their own clean energy, harvest their water and recycle their waste. They grow about two-thirds of their own vegetables. By the 1990s self-sufficiency was no longer a hippie dream but a mainstream possibility.

As well as ideals, fabric was important at Hockerton, with minimal harmful chemicals and maximum use of organic recycled materials. Even so, standard off-the-shelf products have been used wherever possible, as Hockerton residents are keen to spread their knowledge and make their sustainable community replicable. Like the Centre for Alternative Technology, the community provides tours, advice and fact sheets.

As well as insulation and solar gain - by now lessons from the past - this development boasts a wind turbine and a photovoltaic system to provide electricity (although the residents of Hockerton have learned some lessons themselves about the unreliability of wind turbines).

The renewable electricity is only needed for toasters, hairdryers and other gadgets, as the houses are heated by the sun, human body heat and electrical appliances. They use about one-tenth of the energy of a comparable conventional house: approximately 8 to 10 kWh per day.

‘The phrase “zero carbon” wasn’t used at all then. It was fascinating to see the simplicity of it - the trick is to try and leave things out,’ remembers Mr Tilley.

As at Spinney Hill, there is a south-facing conservatory that runs the width of each dwelling to capture heat. Another similarity is the funding: forward-thinking community lenders, who were prepared to back an unusual idea - in this case, the Co-operative Bank and the Ecology Building Society.

But unlike the 1970s and 1980s examples, these homes haven’t tried to look normal for fear of alarming the public - they revel in their striking design. The earth caps of the houses are covered with local plants now, and wildlife from frogs to kestrels. More than 4,000 trees have been planted around the site, including willow for coppicing and wild cherries for birds. Taking a site and improving the ecology is one of many lessons that we still have to learn.

Related stories