You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Co-housing for older women

A women-only co-housing development in London is redefining accommodation for older people. Kate Youde finds out whether social landlords can get any tips. Photography by Jonathan Goldberg

Nineteen years ago, a group of friends headed to the pub. They’d just listened to a talk about collaborative living arrangements for older women, and were so inspired they wanted to set up their own community. “We didn’t want to end up in residential care being looked after,” says Shirley Meredeen, one of the women at the pub that day. “We wanted to take charge of our own lives.”

It took nearly two decades, and this vision has just become a reality, although the former counsellor, now 87, is the only original member of what became Older Women’s Co-Housing (OWCH) who has seen it happen.

The development, named New Ground, opened in High Barnet, north London, in December 2016 to become the UK’s first co-housing community specifically for older people. Its female residents, aged between 50 and 88, have their own self-contained flats but share a common room, guest room, garden and laundry.

Social benefits

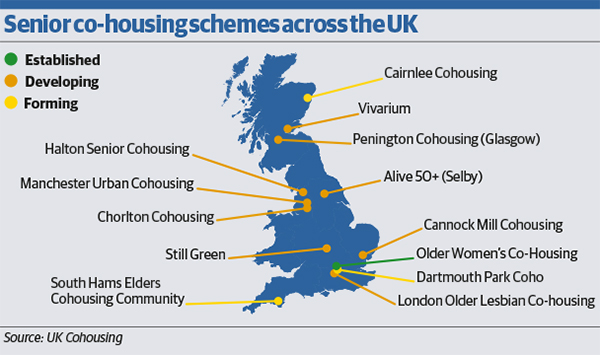

The concept of senior co-housing is well established in the United States, Holland and Denmark and there is growing interest here. A further 12 groups, from South Devon to Aberdeen, are keen to develop schemes – some with housing associations – according to UK Cohousing, an organisation set up to encourage this kind of semi-communal development. But what is the model’s appeal to residents?

“I never wanted anyone to look after me when I get old and dribbly,” says Diana Deeks-Plummer, 75. “When I saw what was on offer for older people I thought I’d have to kill myself because… [it] was disgusting.” What unnerved her were “long corridors of linoleum, doors shut either side” and she felt “desperate” when considering her options “as a person who had no money”.

Retired Ms Deeks-Plummer, who worked as a housing officer at the Girls Friendly Society for a couple of years, moved into New Ground from a housing association “thimble” in Lewisham.

“The concept of senior co-housing is well established in the United States, Holland and Denmark.”

She neither wanted to live with her family – she has four children and three grandchildren – nor accept their money. “I love my kids and they do lots for me but I don’t want anyone to do anything for me out of duty.”

We are chatting over a cuppa in the open-plan living area of her neighbour Josie Pearse’s first floor one-bedroom flat, which has a balcony overlooking the communal garden. The pair, who share an interest in art, are tenants of 923-home association Housing for Women, the freeholder of the new build scheme of 25 flats. Eight flats are let for social rent – enabled by £1.2m from the grant-making Tudor Trust. The remaining 17 are leasehold.

Ms Pearse, 62, who works part-time as a non-fiction literary agent, had been “shuffled down to the bottom” of a council housing waiting list over the past 10 years due to dwindling stock availability. “I am the avant-garde generation rent,” she says. “I was never able to afford to buy somewhere and I got stuck in private renting.” Her new flat is everything she wanted: a “comfortable, peaceful home in a community”.

“I didn’t want to be the old lady in a long street of young families and hipsters, which is what I was in Kensal Rise, really,” she says. “I didn’t want to be the odd one out. I met this group of women and what attracted me to them was the way they work. Decisions are made by consensus by and large.”

It isn’t an easy approach, admits leaseholder Marion Virgo – especially when it comes to deciding whether a resident can have their car on site (there are only nine spaces). “There are a lot of meetings needed,” she says. But maintaining a structure without hierarchy is one of the group’s agreed values. Others include care and support for each other.

Ms Virgo, who was part of the senior management team at a large comprehensive school before retiring, says consensus is easier because the group is all women. “Younger men have got a very different mindset but men of our generation expect to take charge and tend to sulk if they don’t,” says the 74-year-old. “We have had reports from other co-housing groups where that happened.”

OWCH members justify having a women-only group because, they say, there are more older women than men and these women tend to be on their own more and left with fewer resources.

Residents share responsibility for cleaning communal areas and gardening, and meet once a week for a meal together. The shared lounge hosts activities including a film club and yoga.

Ms Virgo, who lives in a three-bedroom flat with her partner Maggs Beltran, says the social benefits of senior co-housing are obvious: “The government has suddenly realised that loneliness is bad for your health and is worried about how lonely so many older people are. We are living so much longer; in fact, you could say it’s taking us longer to die because we are not living longer in good health. We are living longer in bad health statistically, so being in a neighbourhood where we look out for each other is critical.”

“I never wanted anyone to look after me when I get old and dribbly.”

Liz Clarson, former chief executive of Housing for Women, met OWCH and, attracted by the shared recognition of the issues of isolation and loneliness among older women, got the housing association involved in the project in 1999. But the landlord needed a larger association to fund the project and act as developer. Hanover acquired the site at risk, without planning permission, in 2010 and appointed building contractors for the £7m project.

OWCH’s path was full of obstacles. Local authorities “didn’t want to know”, says Ms Meredeen. “They had greater priorities for their land than a group of old women.” And 19,000-home Hanover’s involvement came after failed attempts with a number of other social landlords. “The top-down culture of most housing associations is antithetical to the bottom-up culture of a group like us,” suggests Maria Brenton, a non-resident member of OWCH.

The model is attracting government attention, however. Last year, in its third Housing our Ageing Population: Positive Ideas (HAPPI) report, the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Housing and Care for Older People recommended that more housing associations use their development skills and experience to help the UK’s fledgling senior co-housing movement. So why are associations seemingly reluctant and what can they learn from those that have tested the model?

Anna Kear, executive director of UK Cohousing, says the lack of access for co-housing groups to technical support, which means groups may be seen to lack credibility, is a barrier to associations getting involved. UK Co-housing and other community-led housing organisations are urging the government to re-commit to the annual £60m Community Housing Fund, announced in December, and have proposed community hubs to facilitate projects. “A group with their ideas is talking one language and a housing association talks another language, and there isn’t that place to have that interface,” says Ms Kear. Earlier this year, the mayor of London announced £250,000 for a planned one-stop shop for community-led housing.

Wider issues

The lack of funding for community-led housing – something Ms Kear would like the Homes and Communities Agency (HCA) to oversee – is another concern. Acknowledging that she sounds “poacher turned gamekeeper”, the former Aster development director says there is a “real danger” that housing associations pitch for money from the Community Housing Fund directly – competing against co-housing groups rather than working together – and that there is a need to change the “cultural dynamic of always the housing association having all the power”.

“In terms of the broader picture, with all the issues that have come out of Grenfell, isn’t this the time we say we really do need to listen to people and have a different relationship with the people who live in the communities, and the top-down approach we have had to housing, and that actually we need to revisit that and make it a bit more human again?” she asks.

Cannock Mill Cohousing Colchester (CMCC) wanted to include social housing in its £10m senior co-housing scheme, due for completion in October 2018, but couldn’t make the numbers add up following failed talks with a housing association. “It wasn’t in any sense an equal partnership,” says member Phil McGeevor, 65, a retired academic registrar.

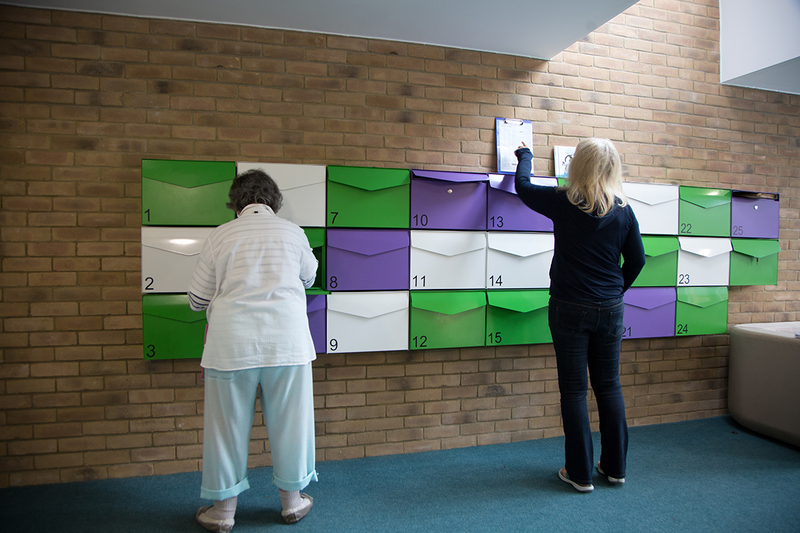

Josie Pearse’s flat, which she says is everything she ever wanted

Earlier this year, CMCC became the first co-housing group to receive a loan from the HCA’s Home Building Fund. The £3.9m will underwrite construction costs until members can purchase their properties in full.

Unable to compete with large developers with deep pockets, co-housing groups face problems acquiring land. Mr McGeevor would like central and local government to earmark land they are selling for co-housing groups, as long as groups raise the money within a defined period.

Alan Henderson, land and planning manager at Kingdom Housing Association, which is in talks with the Vivarium Trust about a potential scheme in Fife, warns that developing co-housing is a protracted process, partly because a group may have specific demands regarding sites and undergo changes in membership, but believes it is worth persevering.

“It’s easier just to carry on doing what we are doing at the moment – because there’s no doubt that [co-housing] is challenging – but I think if the housing association movement can get together in some more structured way with the world of co-housing, and groups seeking to pursue it, we can all learn from each other.”

Claire Anderson, deputy director of development at Hanover, “aged prematurely” working on the OWCH scheme. “Without being too flippant, dealing with a group of feisty, knowledgeable, determined older women is no mean feat so actually one of the key things [to learn] here is ensuring the group is a complete group before you start,” she says.

A co-housing group must make difficult decisions so she says it is key to have protocols in place for how they will work together and the hierarchy for decision-making, as OWCH did.

The benefit to Hanover was “learning first-hand exactly what these end users want and feeding that back into our more general policies and procedures”, adds Ms Anderson. “The disadvantage is that takes a huge amount of time and effort because you are dealing with a group of predetermined residents,” she says.

Mailboxes in the Suffragette colours

A co-housing group must make difficult decisions so she says it is key to have protocols in place for how they will work together and the hierarchy for decision-making, as OWCH did.

The benefit to Hanover was “learning first-hand exactly what these end users want and feeding that back into our more general policies and procedures”, adds Ms Anderson. “The disadvantage is that takes a huge amount of time and effort because you are dealing with a group of predetermined residents,” she says.

Hanover is “nervous” about pursuing future development, including co-housing, because of the potential impact of the Local Housing Allowance cap so has no plans to do more. Zaiba Qureshi, chief executive of Housing for Women, believes it is “a valuable model” that the association will look at again if the opportunity arises as there is a need to “think creatively for older people”.

Ms Qureshi says Housing for Women learnt the need to establish roles on a project clearly as some boundaries were “blurred” because OWCH members were on site meeting Hanover’s contractors. She says it will be interesting to see the future dynamics at New Ground as new tenants will be moving into an established group.

However OWCH recognises the need to get to know new people and make them feel welcome. It pairs potential members with a buddy (an existing resident) and invites them to group activities, and there is an interview process. The group will have a pool of about a dozen non-resident members who meet the criteria to be potential renters or buyers. There is no waiting list and the local authority doesn’t have nomination rights.

Ms Qureshi believes there is potential for reduced management costs at New Ground but, as it is still in the defects period for maintenance, a clear picture will not emerge until next year.

“Obviously we are the landlord – we know what our obligations are – but other than collecting the rent and making sure repairs are done, we have very little contact with the women,” she says. Management is “less hands on” than other schemes because residents “get on with a lot of things”.

As she shows Inside Housing out, Ms Meredeen points out the mailboxes, painted in the “Suffragette colours” of purple, green and white. It reminds us of what she said about how the scheme shouldn’t have taken 19 years: “We suffer for others not to suffer quite as long as we did.”