You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Mind your headroom

Ten English councils have reached or gone over their borrowing caps. Tom Wall finds out what they are doing differently to other councils.

It was the biggest shake-up of the way council housing was funded in a generation. It was going to free up town halls to better manage their own stock. It was going to usher in a new era of council housebuilding.

Yet the coalition government’s 2012 self-financing settlement – which gave councils control over their rental income and the ability to borrow up to a cap – hasn’t quite lived up to its promise.

Five years since the deal, council housebuilding is in the low thousands. This is better than the figures for the early 2000s, when councils managed only a few hundred homes each year. But it is well below the 3,000 to 5,000 homes per year councils were planning to build once they gained control of their finances. And nowhere near the amount local authorities need to be churning out to help meet the government’s target of one million new homes by 2020.

Fiscal challenges

John Perry, the co-author of Investing in council housing, a report examining the settlement for the Chartered Institute of Housing, says at the time of the agreement councils were so certain self-financing would be a good thing that they agreed to take on £13bn worth of government debt to compensate the Treasury for loss of income.

Initially, the settlement appeared to be working: ambitious investment plans were drawn up and councils started building more homes. But former chancellor George Osborne’s surprise move in 2015 to cut social rents forced councils to dramatically scale back their plans as they could no longer expect the same rental income.

“The government didn’t keep to the deal. Within in a year, they had put an inflation limit on rent increases and then in April 2016 they imposed a 1% reduction on rents every year for four years,” explains Mr Perry.

Ministers also boosted Right to Buy sales by upping the discount available to tenants from Labour’s £16,000-£38,000 to a maximum of £75,000. This reduced long-term rental income streams even further. And welfare reforms, including the bedroom tax, the benefit cap and benefit sanctions, have made it harder for councils to collect rent.

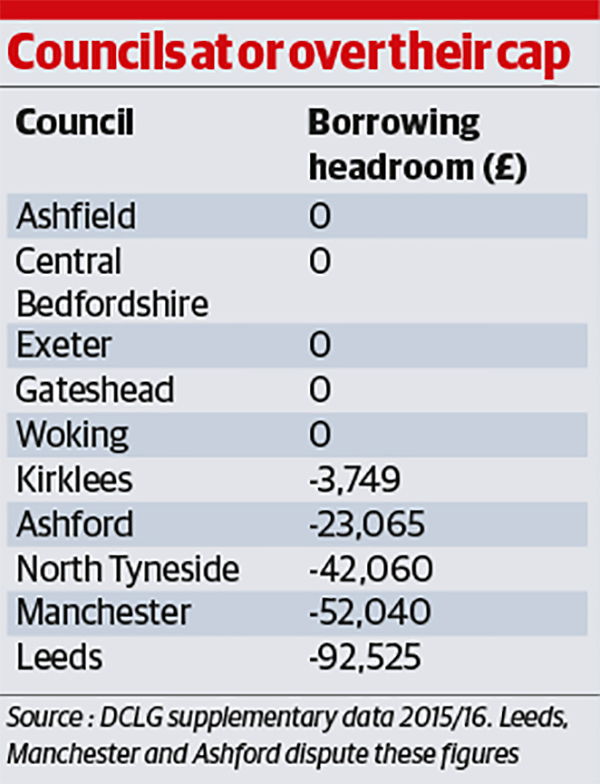

Although all councils have faced these same fiscal challenges, they are responding in very different ways. Figures compiled by the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) for 2015/16 reveal some contrasting approaches to debt. While most local authorities have stayed below their caps, five have gone to the very limits of their caps and five more appear to have gone over their caps.

So what are these 10 councils that are at or over their cap doing differently?

Exeter City Council, which has borrowed up to its maximum of nearly £60m, puts it down to investing in new homes.

Hannah Packham, portfolio holder for the Housing Revenue Account (HRA) at Exeter, says: “The reason we are approaching the government’s cap is that we took advantage of the low interest rates offered through the Public Works Loan Board for an exciting programme of new build homes and significantly investing in our housing stock.”

Reaching limits

The Labour-run council completed 20 homes in 2015, more than any other authority in the South West. But Mr Osborne’s rent cuts hit the council’s plans and it built no houses in 2016.

“The rent reduction introduced by the government in 2015 [it came into effect in 2016] hasn’t helped and effectively means that we have an £8m reduction in revenue; this has meant that we are no longer able to prioritise new build schemes due to the competing demand for investment in existing stock,” Ms Packham says.

Nonetheless, Exeter Council, which owns 4,970 homes, is keen to engage with the government if it goes ahead with its 2017 manifesto pledge to make it easier for ambitious councils to borrow. “We continue to work to find innovative ways of building more homes, and would of course welcome any proposals from government which enable us to deliver more affordable, social and council housing for the people of Exeter,” says Ms Packham.

Woking, which is at its £124m limit, blames the original settlement as the council was left with no borrowing headroom. Ray Morgan, chief executive of Woking Borough Council and a straight-talking accountant with a passion for housing, describes the settlement as a “sham” and accuses the government of making it harder to build new homes.

“We were already at the borrowing limit when the HRA was transferred. We started with no scope to make any investment,” he says.

Conservative-controlled Woking found itself in this bind because it had managed to borrow before the cap was enforced. Mr Morgan says the cap effectively punished the council for investing and left it with no choice but to put its plans on hold. “They completely shut down our ability to develop or buy new homes,” he says.

The council neither started nor completed any homes in 2012 or 2013. Mr Morgan, however, recognises there were some positives. Like many councils, 3,350-home Woking had been paying more in rental income to the Treasury than it was getting back. “It reduced the negative subsidy we were paying to the government,” he says.

And Woking has recently found one way to get around the cap: it is using money from its general fund to create some borrowing headroom. “We’ve sold some commercial properties on estates to the general fund. That gives us the ability to raise £11m to £12m worth of debt,” he says.

In 2015 it completed 120 homes; last year it completed 170 homes.

Gateshead Council also blames what it sees as an unfair settlement, which left it at the limit of its cap at the outset. Keith Purvis, the council’s deputy strategic director of corporate finance, says the £345m cap has restricted its ability to regenerate areas of the town.

“Councils were happy with the deal by and large because they wanted the freedom to borrow and invest.”

“The discussions highlighted that the limit would severely restrict the council’s ambitions to maintain decency and support the regeneration of Gateshead,” he says.

The North East authority, which has 19,690 homes, has only built 50 council homes since 2012, with nothing built in the past two years.

“Given that the council was at the debt cap from the outset, it has had to prioritise resources towards meeting essential priorities within the existing stock as there has been no financing headroom that would have enabled further regeneration work, including the construction of additional dwellings, to be undertaken,” Mr Purvis explains.

Skewed figures

But what of the five councils that have gone over their limits? Ashford Council in Kent, which appears to be around £23m over its cap, according to DCLG figures, says it has borrowed up to its limit in order to deliver more homes.

Sharon Williams, head of housing at the 5,030-home council, says: “Ashford has taken the view of maximising its ability to borrow up to the debt cap to maximise delivery of new homes within the HRA. We have now delivered somewhere in the region of 250 homes by utilising debt cap, Homes and Communities Agency grant and of course one-for-one monies in relation to capital receipts from Right to Buy sales.”

Ms Williams blames the inclusion of a private finance initiative (PFI) project for distorting its borrowing figures and appearing to push the council over its limit. “We are not in breach of our debt cap,” she says. “The amount we appear to be over is the amount of the PFI.”

Indeed, DCLG allowed the Conservative council to increase its debt cap last year by around £1.3m to purchase 21 affordable properties on a new housing development in a village. This could not have happened if the council had been over its limit.

Leeds City Council, which is £92m above its debt cap, and Manchester City Council, which is £52m above its cap, both claim PFI schemes have skewed their figures.

DCLG says PFI schemes should not be included in housing debt calculations. Officials plan to work with councils to make sure they fill in their forms accurately next time. But the department will not be recalculating the figures for 2015/16.

The experience of councils at or over their caps is varied, with some seemingly the victims of accounting quirks and tight financial settlements. But others have used their headroom to build modest amounts of new social housing.

Ms Williams suggests the key difference for those with borrowing headroom might be political will. Ashford, she says, was determined to build and was not afraid of borrowing. “Ashford is maximising its borrowing capacity to deliver additional homes. Some other councils have taken a decision that they don’t want to see too much debt on the council books.”

These divisions could become more apparent if the government raises the cap of councils keen to build, although it is hard to imagine too many borrowing at scale until the sector has a reliable revenue stream from rents.

“Council housing business plans don’t really exist at the moment because of the uncertainty about what rent policy will be post-2020 and what the high-value levy will be,” says John Bibby, chief executive of the Association of Retained Council Housing.

This is frustrating for councils determined to build. They know social housing is desperately needed and ultimately pays for itself.

“If you are building housing at social rents you are reducing the benefit bill because you are housing more people in lower-cost rented property,” says Mr Bibby. “And ultimately you’ve got a rental income stream that lasts for 60 years whereas your debt borrowing is over 30 years.”