Networked heat: what we know about Scotland’s district heating plans

Gavriel Hollander examines the local heat and energy efficiency plans released by Scottish councils

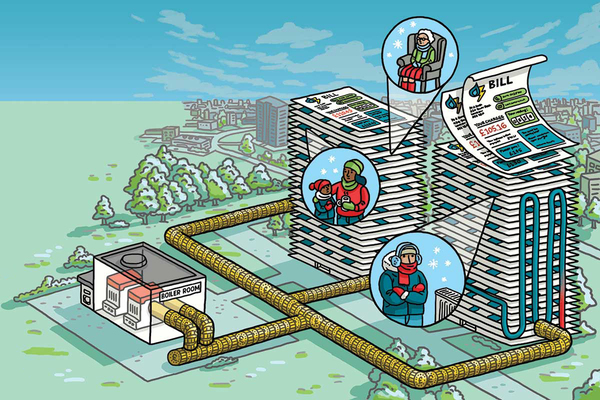

The increased use of district heating networks has long been touted as a potential solution to the problem of low-carbon heating and energy efficiency for both domestic and commercial buildings. In Scotland, thanks to a recent edict from the Scottish government, these networks could finally be about to have their day.

In 2022, the government in Holyrood passed legislation that required all 32 local authorities in the country to develop a local heat and energy efficiency strategy (LHEES) and publish them by the end of 2023. These strategies and their complementary delivery plans are intended to set out a pathway for decarbonisation and could lead the way to a massive expansion of heat networks. Indeed, the Scottish government has set a target of 3% of national heat demand to be met through such networks by 2027, and 8% by 2030.

The plans could also be transformative for social landlords in Scotland, as they seek to decarbonise their stock. The idea is that local authorities will designate zones for potential heat networks, allowing housing associations to map out which of their homes could benefit from them.

Duncan Smith, head of energy and sustainability at River Clyde Homes, has worked with local and national government in Scotland on energy efficiency in housing for more than 15 years. He says that the notion of creating zones for different energy efficiency interventions mirrors a strategy developed in Denmark in the 1970s, when the Scandinavian country was forced to respond to high energy prices caused by the oil crisis of 1973.

“The zones themselves send signals to the market about investment opportunities,” he explains. “Councils can say that they’ve got 40 zones and for, say, 25 they need to look at heat networks because it’s a perfect solution, and maybe for these other 20 there needs to be a different solution, so you might need to look at fabric-first or heat pumps.”

Improving energy efficiency

Paul Steen, head of business development in Scotland for Swedish power company Vattenfall, says that the delivery plans in particularly could prove useful for housing associations looking to develop strategies around resource management as they try to improve energy efficiency.

“These plans would enable them to see where their property assets are and enable them to understand what solutions will be coming forward under the local authority and that those housing associations can participate in,” he elaborates. “Associations will be able to identify where their homes will connect to heat networks and where they are less likely, and so where they’ll need to think in the near term about alternative solutions for decarbonisation.

“It could save them an awful lot in development costs compared to trying to solve the problem themselves. There’s also time and effort saved if there’s already a ready-baked solution that’s been brought forward by the local authority.”

Given that the LHEES have typically been published in consultation form so far, with final versions likely to emerge only after stakeholders get a chance to have their say, there is also a real opportunity for associations to get involved in shaping the councils’ plans at an early stage.

The strategies released so far by the 32 councils vary greatly in terms of depth and detail. While some give precise details of the location of all proposed heat networks, others are more vague, simply making promises to explore their options, while others have yet to be put in the public domain. The discrepancy is partly down to the varying level of resources across Scottish councils, but it is also likely because the guidance from government is not prescriptive in terms of what has to be in the strategy documents.

“I think they are a mixed bag,” admits a source with experience of working on decarbonisation projects at Scottish local authorities. “Some of them are OK, but some are pretty poor. Some of that is because of resources and lack of imagination and lack of vision, but it’s also about the size and scope of the remit councils have been given. The guidance isn’t prescriptive and is a little bit woolly.”

Glasgow and Edinburgh

So what do the plans that have been released show in terms of the potential scope and scale of heat networks?

The most detailed plans come from the two largest local authorities by population: Glasgow and Edinburgh city councils. Here, the potential for heat networks is greatest, thanks in large part to the denser populations and greater availability of possible connections to anchor loads – buildings with significant heat demand that make the networks more viable.

In Glasgow, the council has identified 21 zones across the city where heat demand makes a network viable. These could eventually reach up to 46% of the city’s population, according to the strategy document. Where heat networks aren’t viable, the strategy would be for heat pumps to replace the gas boilers that currently dominate the city.

Glasgow’s LHEES also provides an example of what Mr Smith describes as councils sending ‘signals’ to the market over their intentions. The strategy document says: “For heat networks to succeed in Glasgow, the sector’s investibility must improve. This will require a comprehensive mix of policies at local and national level, designed to ensure that there is minimum additional cost compared to gas and to maximise the incentive to switch. The cost of heat compared to conventional fuels like gas is a key driver of this, but heat networks must also be shown as the most cost-effective decarbonisation option for buildings within indicative heat network zones.”

The council adds that the delivery plan should include actions that could “lower the risk attached to investment and connection”, and that stakeholders “must work to build the case for heat networks”. In other words, this is the start of a potentially long journey towards much larger heat networks – and that journey is a necessarily collaborative one, which is where housing associations will have a role.

“It gives signals as to the solutions available,” says Vattenfall’s Mr Steen. “So housing associations will be able to work with the authority, participate in consultation about how to take forward the delivery plan, and have some influence over where activity happens first.”

Heat network zones

Edinburgh’s plan would see the creation of 17 heat network zones, which the council says would “cover a significant proportion” of the Scottish capital. Collectively, the zones represent more than 3.7 million megawatt hours of heat demand.

Few local authorities are as clear cut about their intentions for heat networks at this stage. Fife Council, for example, has undertaken analysis of 46 zones for potential networks, which would cover around 16% of the area’s demand. But in its delivery plan, the council commits only to identifying opportunities for new networks and optimising existing ones.

North Lanarkshire, meanwhile, gives detailed maps of potential heat networks. However, the zones identified represent only around 6% of domestic and 11% of non-domestic properties, which is a far cry from the numbers potentially benefitting from new networks in more built-up areas. As the strategy document says: “These low percentages highlight that heat networks are not the primary route to low-carbon, affordable heat for everyone in North Lanarkshire.”

That said, even rural areas are not ruling out heat networks. The Highland Council’s LHEES lists five projects either being developed or at feasibility stage. The council is working with the Scottish government’s Community and Renewable Energy Scheme (CARES) to look to grow these networks. However, the delivery plan published by the council doesn’t go beyond a commitment to feasibility studies and stakeholder engagement when it comes to expanding existing networks.

River Clyde’s Mr Smith says that one potential pitfall of the national strategy is that the ideal way to distribute heat networks doesn’t necessarily follow local authority boundaries.

“For heat networks to succeed in Glasgow, the sector’s investibility must improve. This will require a comprehensive mix of policies at local and national level”

“It’s not to say it won’t work, it’s just to say that the problem is a national and regional one,” he explains. “While local authorities are good administrators of public money, they are not necessarily the geography that you want to use for providing heat networks.

“You can look at two or three local authorities that are in a single geographic region and it would make more sense for them to do something together and pool resources and finances to develop a solution that was for that region.”

Works in progress

The strategies published are still very much works in progress, despite the national government’s deadline. Edinburgh notes that it is yet to go through a statutory process to designate its heat zones, and lays out the potential challenges it faces before they can be agreed on. These include: problems developing “cost-competitive propositions for off-takers” while gas remains an alternative option; difficulties securing connections without a legal requirement for buildings to connect to networks; and potential issues securing sites for the required energy centres and substations, particularly in more densely populated areas.

The challenges councils such as Glasgow and Edinburgh might face in so massively expanding their heat networks mean that many are likely to form partnerships with the private sector to build and manage them. City of Edinburgh Council itself is tendering for a partner to take forward a network in Granton and may do the same with others.

This model is already in place in Midlothian, where Midlothian Council formed a 50/50 joint venture ESCo (Energy Services Company) with Vattenfall in 2020. The ESCo – Midlothian Energy – delivers various low-carbon energy projects for the council, including a district heating network in the new town of Shawfair.

Mr Steen says the point of working in partnership is not for the partner to deliver a pre-defined solution, but for the local authority to work alongside that partner to find the most appropriate solution. That is why the LHEESs that councils have so far tend to list options rather than provide a detailed plan.

“If local authorities think they need a partner, they should procure that partner early,” he says. “We believe that local authorities are served best by procuring a partner before defining the solution. They should work with and set the strategy together as the partner will be the one to deliver that solution.”

For Mr Smith, the element of partnership working shouldn’t stop at a single delivery partner, but should involve as many stakeholders as possible at every stage, which is where opportunities for housing associations come into play.

“This should be about a collaborative engagement with different stakeholders about decarbonising,” he continues. “Some councils will be really engaging and inclusive, and some will have a top-down hierarchical approach, but unless you collaborate and unless you engage, you’re not going to get it right.”

The huge variety of detail in the plans so far suggests that this is still early days. But if there is going to be a heat network revolution in Scotland, it seems likely that social landlords will have an important role to play.

Sign up for our Scotland newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters

Sign up to the Retrofit and Strategic Asset Management Summit

Learn how to develop long-term and joined-up strategies that simultaneously tackle energy efficiency, damp and mould, Decent Homes, building safety and fuel poverty.

Join over 500 sector leaders to ensure your capital investments go further and deliver healthy, warm and safe homes for all tenants and residents.

Related stories