The Grenfell Tower Inquiry: six things we learned in September

September’s evidence at the inquiry was dominated by cladding sub-contractor Harley Facades. Peter Apps explains six key takeaways

The past month at the Grenfell Tower Inquiry has been dominated by evidence from the sub-contractor commissioned to design and install the cladding system, Harley Curtain Wall (later relaunched as Harley Facades).

Towards the end of the month we also heard the evidence of witnesses from the company that cut the cladding to shape and sold it on, and the clerk of works. Here are the key details that were uncovered.

Harley Facades’ role

Pinning down exactly what Harley Facades was responsible for doing at Grenfell Tower is made more complex because it never signed a formal contract for the works.

Instead, in July 2014 it was given a ‘letter of intent’ authorising it to carry out £30,000 of design works. By September, with no contract in place, the amount of work to be carried out under the letter was extended to the full £2.6m cladding job. This letter therefore represents the only contractual position between Rydon and Harley, even though – for reasons unexplained – Harley did not actually sign it.

The letter’s terms made Harley responsible for the design of the facade “including relevant compliances” and referred to the main contract Rydon had signed, which included reference to various documents spelling out the potential fire risk of using combustible materials.

But when Ray Bailey, managing director of Harley, was asked if this meant “the buck stopped with Harley” with regard to the safety of products and design, he insisted it did not. He said that “ultimately”, the firm was reliant on building control inspectors at the council to ensure its designs complied.

“Are you telling us that, even though Harley was a specialist cladding sub-contractor with a lot of experience, particularly in relation to overcladding high-rise residential buildings, you nonetheless relied on building control to tell you whether or not the products and design complied with the statutory requirements?” asked Richard Millett, counsel to the inquiry.

“We are not statutory compliance experts, so when we have a doubt about how something is done, we seek guidance, and building control are the experts on compliance,” Mr Bailey replied.

It also emerged that Harley went bust during the job, with Harley Curtain Wall placed into administration in September 2015 and the job transferred to a dormant company also owned by Mr Bailey, Harley Facades.

Why the insulation was specified – and switched

Andrew McQuatt, project engineer at consultancy Max Fordham, first suggested Celotex

The Celotex insulation used on the walls of Grenfell Tower was made of a combustible plastic called polyisocyanurate, which burns when ignited and lets off a toxic mix of gases including cyanide. It did not meet the basic standards for compliance on a high-rise building, so what was it doing on the tower?

Witnesses have shed some light. Andrew McQuatt, project engineer at consultancy Max Fordham, was the first to suggest the use of a Celotex product for the tower. It was a matter of chance: when he was making calculations about which insulation products would work on the tower, he happened to have a login for Celotex’s website to hand.

He was trying to find a way to meet the “ambitious” insulation target his firm had set (double the minimum requirement) and believed that a rigid foam board was the only option. Along with the architects, he had discounted the use of non-combustible rock fibre insulation on the basis that it would need to be too thick to meet challenging targets. The inquiry’s expert witness Paul Hyett disputes these calculations, and in his evidence Mr McQuatt accepted that Mr Hyett’s numbers were “a bit more accurate”.

When specialist cladding sub-contractor Harley Facades was appointed in 2014, it did not question the decision to use combustible insulation. Managing director Ray Bailey said that these products had become common on high rises since the late 2000s and he believed they were compliant “providing they met certain criteria”.

He gave two main reasons for believing they did: Celotex’s use of the phrase “Class 0 throughout” in advertising the product. He said he mistakenly took this to mean that it had a good enough fire performance for high rises. Further, Celotex had advertised the product as “acceptable for use on buildings above 18m”. This was based on a test pass

as part of a system that comprised cement fibre cladding panels – and it was only ever permitted in exactly this system.

Mr Bailey claims that Celotex was contacted for confirmation that this combination being used on Grenfell was compliant, but accepted when shown emails between the two companies that they did not say this. Nonetheless, he was adamant assurances were received that the product was being used correctly.

Celotex advertised the insulation that was used on Grenfell as “acceptable for use on buildings above 18m” (Picture: Alamy)

“Did you just take it on trust from Celotex… Even though they had a vested interest in making sure you bought the product because they were making it and selling it?” asked Richard Millett.

“Yeah. Why… how… why would they lie to us?” Mr Bailey replied.

Later, Ben Bailey, his then 25-year-old son and project manager, was grilled about the actual purchase of the Celotex boards, for which Harley received a 47.5% discount, followed by a request from Celotex to use Grenfell as a “case study” for the product’s use on high rises.

“Did you get the impression that Grenfell Tower was, as it were, a guinea pig for RS5000?” Mr Millett asked.

“That’s not a thought that crossed my mind,” Ben Bailey replied.

He also explained why Celotex was partially substituted for a Kingspan product mid-installation without the knowledge of the client – Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCTMO).

The supplier of Celotex mistakenly sold a batch meant for Grenfell elsewhere, leaving a delay in delivery. Ben Bailey then ordered K15 as a replacement to avoid a delay of just four working days on site. He believed that the products were, essentially, interchangeable.

There were major missed opportunities over cavity barriers

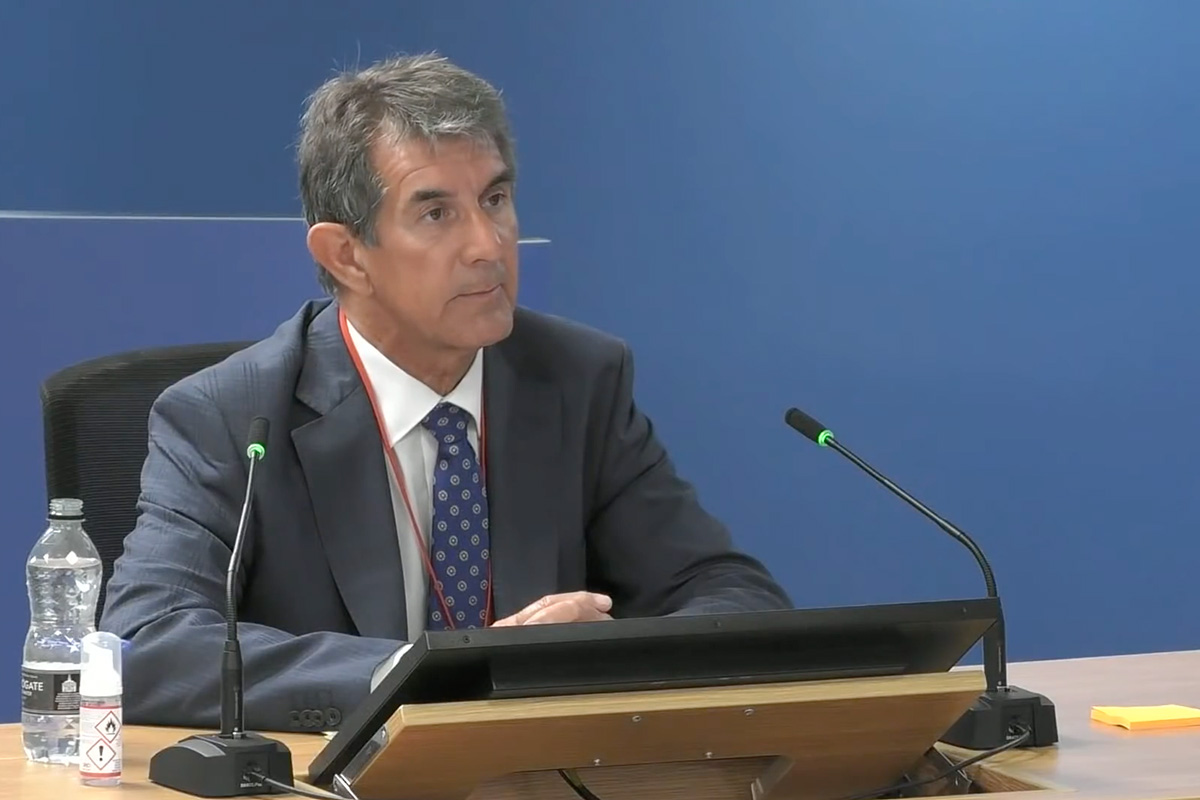

Ray Bailey, managing director at Harley Facades, was questioned about cavity barriers

There were major missed opportunities over cavity barriers

A major task for this stage of the inquiry has been pinning down the responsibility for cavity barriers. These are intended to slow the spread of fire in a cladding system, but at Grenfell they left much to be desired.

One critical error appears to have been their absence at the head of the windows as required by guidance: fire rapidly broke out of the window on the fourth floor to ignite the system, then into the windows of flats as it ripped up the tower.

Kevin Lamb, the freelance designer who drew up the blueprint for the cladding system for Harley Facades, was grilled on this in minute detail. It emerged that his initial designs in summer 2014 included no cavity barriers at all, and they were not added in until March 2015. When they were, he sketched them only between floors and on the vertical columns – not at window heads.

Ray Bailey was asked about a prior fire at a Harley project in Camden, where a report specifically identified the cavity barrier as being important in stopping the flames from spreading out of the window.

He told the inquiry he believed that where there was only one window in a ‘compartment’ (in this case, each flat) it was acceptable to have barriers at the edges of the compartment, not at the window. This is not, however, what building regulation guidance shows.

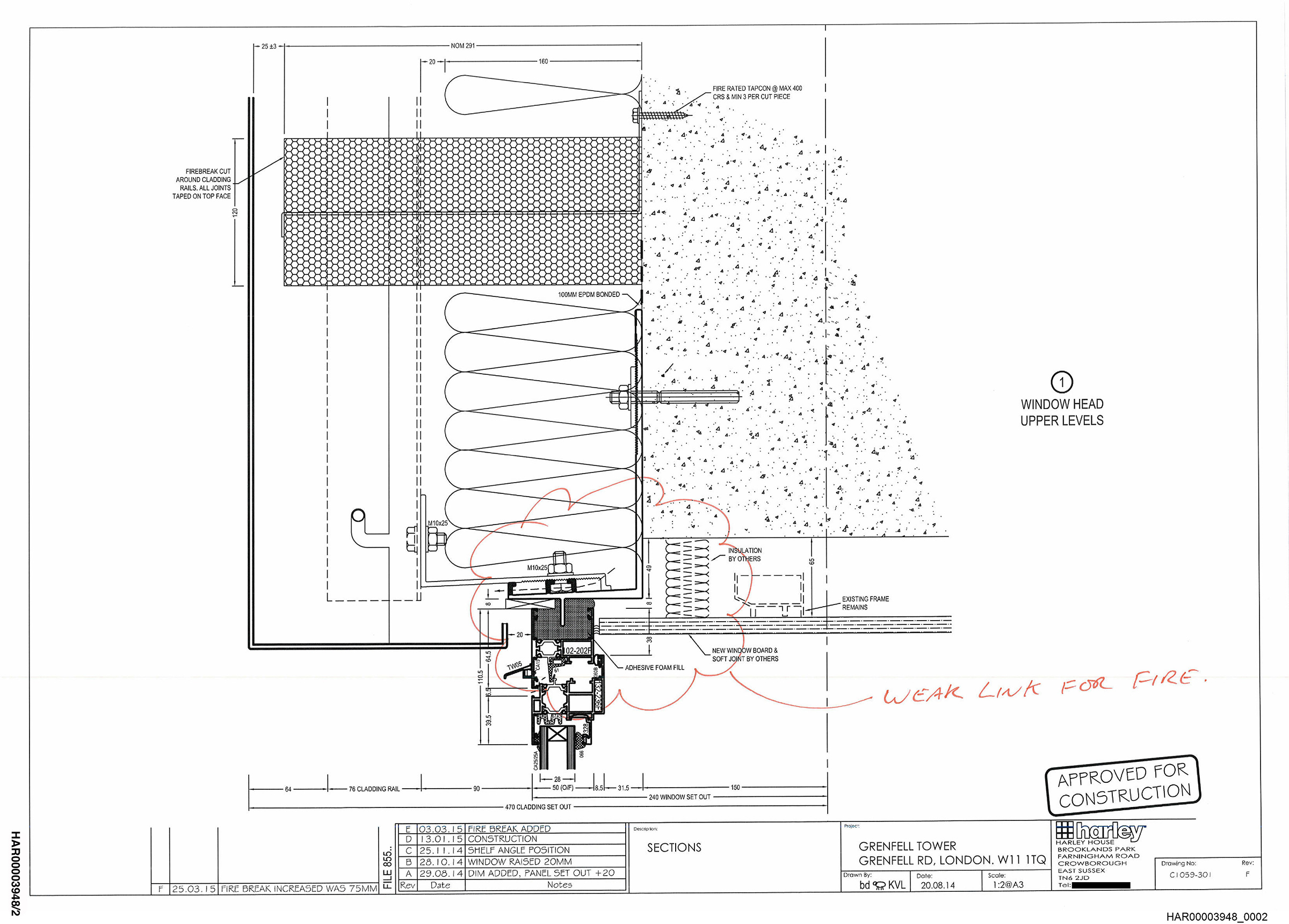

When Ben Bailey gave evidence, the most stark warning was discussed. In an email chain with cavity barrier supplier Siderise, Chris Mort, the firm’s technical development director, specifically identified the head of the windows as a “weak link for fire” (pictured above) and annotated Harley’s drawings to bring the barrier down.

But Mr Bailey did not act, and he did not forward the email to the architects to fix the issue. His evidence is that he believed the concerns Siderise was raising related to a separate proposal to include two-hour fire-stopping in the system – a plan that was dropped shortly afterwards.

“Why did you not go back to Mr Mort and ask him what he meant?” Mr Millett asked.

“I don’t know,” Mr Bailey replied.

The background to the selection of the deadly cladding

Geof Blades, a sales director at CEP Architectural Facades

We had already heard much about the ‘value engineering’ process that drove a shift from solid zinc cladding to deadly, combustible aluminium composite material (ACM). In September we learned about the background to that decision, with two witnesses questioned on whether they were applying soft pressure to drive the purchase of ACM.

First up was Mark Harris, commercial manager at Harley, who met with lead architect Bruce Sounes in September 2013 to discuss cladding options, and showed him brochures of other jobs that had used ACM.

When asked to provide details of a zinc cladding system, Mr Harris instead sent ACM options and emphasised the £500,000 saving that could be made by switching.

“From a Harley selfish point of view, our preference would be to use ACM. It’s tried and tested on many Harley projects,” he wrote at the time.

Mr Harris explained at the inquiry: “I was alluding to the fact there that Harley had great experience using ACM and liked using the product.”

Later, the inquiry heard from Geof Blades, a sales director at CEP Architectural Facades, the company that cut the panels to shape and sold them on.

He introduced Deborah French, UK salesperson at Arconic, the company that made the Reynobond ACM, to the job in 2012. And in 2013, when asked to provide quotes for zinc, he instead offered quotes for Reynobond – painted to look like zinc.

“You put forward Reynobond when you weren’t asked for it – that’s right, isn’t it?” Mr Millett asked.

“Yes, at this point,” Mr Blades replied, explaining that he felt he was offering an option that would be “suitable” for the job.

When the product was eventually selected for the tower in 2014, Ms French emailed them both to say: “Thank you for your hard work and perseverance in putting Reynobond forward. I think I owe you [Mr Harris] and Geof either lunch or dinner at some point.”

Both witnesses emphasised that they did not receive any incentives to promote Reynobond products.

The checking process had serious flaws

Richard Millett, counsel to the inquiry, questioned Harley about its “ad hoc” inspections

The Grenfell Tower refurbishment did not want for a second pair of eyes. The architects’ original proposals were seen by Harley Facades, which itself contracted a freelancer with specific cladding experience.

On site, the installation of the cladding was monitored by Harley as well as Rydon, with a clerk of works also employed to keep an eye on developments, all backed up by building control officers at the council.

So how did such critical mistakes slip through? The answer emerging is that the actual checking was insufficient.

Ben Bailey, as project manager at Harley, was responsible for checking the work being carried out by Osborne Berry, the building firm that Harley brought in to install the cladding.

This checking was limited. In his witness statement, Ben Bailey described his checks of the window installations as “ad hoc, informal” and accepted that he did not inspect the south face of the building at all. He had no formal checklist or tracking system, simply scribbling notes into a notebook.

He said he did not see any of the poor workmanship discovered afterwards: cavity barriers incorrectly cut, and installed upside down or vertically when they should have been horizontal.

He said he may have missed these things because they were covered up by insulation by the time of his inspections.

“Do you accept that’s because you weren’t inspecting regularly enough?” Mr Millett asked. Mr Bailey said it was possible the insulation was installed at the same time as the cavity barrier.

Jon White, the clerk of works, told the inquiry that he was not employed as a clerk of works at all but instead as a site inspector, with more limited responsibilities. This is despite everything down to his email signature describing him as a clerk of works.

His contract included a stipulation that he be “familiar with legal requirements and checking that the work complies with them”, and that he check design drawings.

But he did neither, insisting under questioning that his job was to focus on other matters. He claimed to have little knowledge of the rules that applied to cladding systems, and said he was there on instructions from KCTMO to keep an eye on “key performance indicators” and the interactions between the contractor and residents.

He made at least 10 trips up the tower, but thought little of the compliance of the materials being used, impressed instead that the workmanship appeared “neat”.

He said: “If a job looks neat and tidy, it’s a good way of knowing it’s being done properly.”

Safety was barely an afterthought in design

Daniel Anketell-Jones, design manager at Harley Facades

What about the designers? In September we heard from two of the people who worked on the detailed cladding designs at Harley Facades: design manager Daniel Anketell-Jones and freelancer Kevin Lamb.

But neither designer felt it was their responsibility to make sure the materials being selected for the tower were safe.

Mr Anketell-Jones often responded by stressing that during the refurbishment, his design responsibilities stretched only to structural design and he was not educated in fire safety at the time.

However, emails he sent suggested that he did have a bit more knowledge than he let on. For example, he listed details of testing requirements for insulation. He argued that they were copied and pasted from emails sent by others.

He was happy to offer an opinion about ACM, however. In March 2015, he wrote in an email: “There is no point in ‘fire stopping’, as we all know, the ACM will be gone rather quickly in a fire!”

Like others, he has argued that this indicated a belief that panels would not resist fire, but that he did not know they would ignite and send fire ripping around the building.

Mr Lamb, meanwhile, argued that he was merely drawing out the brief already decided by others and made no contribution to the decisions about materials. In this instance, the evidence differed from Harley’s. Mr Anketell-Jones said that as far as he was concerned Mr Lamb was responsible for his designs and would be sending them

to Rydon and the architects.

He later admitted that there were no quality control processes in place to check Mr Lamb’s work and that it was his role to check only that Mr Lamb was working to the programme and meeting deadlines.

Mr Lamb said it was his assumption that he would be closely supervised by Harley’s management. He said that he would send all his drawings to its team to be checked, and that design meetings took place regularly.

When asked whether he understood he would be getting supervision from Harley, Mr Lamb said: “Yes, you wouldn’t expect a client to employ a third-party design source and let them get on with it, that would be very dangerous indeed.”

Sign up for the IH long read bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters