Bristol’s new broom

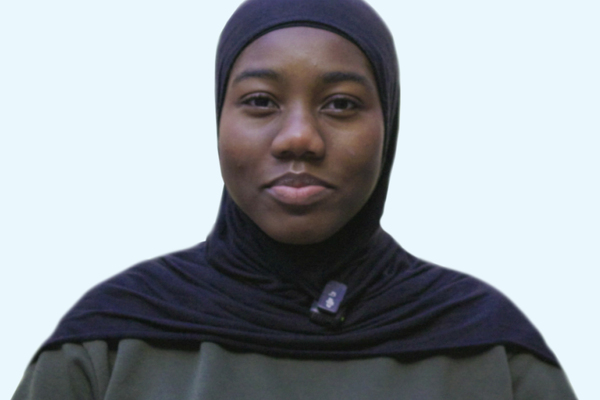

Britain’s first directly elected black mayor, Marvin Rees, swept to power in Bristol in May. He tells Tom Wall how growing up on a council estate shaped his views and how he will transform his home town

Video:

Features code

A gaggle of fresh-faced kids from Lawrence Weston, a post-war council estate on the outskirts of Bristol, are trying to guess what car the city’s recently elected Labour mayor Marvin Rees will be turning up in. An Aston Martin? A Porsche? A Google driverless car?

When the mayor arrives in a Ford Fiesta, you’d think they’d be disappointed. But they leap up from their battered BMXs and mob him like an Olympic champion. With the charm that helped him sweep to victory in spring, Mr Rees poses for photos (inset right) and chats about growing up on the estate.

“Did you ever shimmy up between the garages at the back? I used to love doing that.”

“I lived just there with my mum,” he says, pointing to a modest ground-floor council flat. “Did you ever shimmy up between the garages at the back? I used to love doing that.”

Before they part he gives them his mobile number so they can arrange for him to speak at their school. It’s clear that he has the single attribute that many modern career politicians crave: to talk and act like a human.

“I come here fairly frequently, just to visit where I came from, where I spent those early years. It’s special. It’s nice to get a reception like that.”

Video:

Ad slot

His mum arrived in Lawrence Weston after a spell in a refuge in Devon. The family later moved to another part of Bristol but the estate left a big impression on Mr Rees.

“My mum was single. She was white and had a brown baby. We’d just come from a refuge.”

“I look back on it with a nostalgia but it was tough. My mum was single. She was white and had a brown baby. We’d just come from a refuge.”

The estate sits below steep wooded hills. There is plenty of space for kids to play in but it’s a long way from the amenities of the city centre.

“We didn’t have a car so to get into town was a bus ride. So while I have memories of adventure - we’d go climbing in the fields round the back - it was also quite a feeling of being locked out and a bit lost.”

Nor was it easy being one of only a few black children on the estate: “I was the only brown-skinned kid around. There were a couple of other families. But in my school I was the only kid who wasn’t white.”

He was called names but accepted it as a part of life. “I knew I was different. But as a six-year-old you don’t understand that stuff fully. You are in the middle of this experience of being different and feeling vulnerable.”

The Bristolian’s route from council estate kid to mayor of his hometown was a convoluted one: after being turned down by the Royal Marines because of a minor eye defect, he went to Swansea University to study economics and politics, and then Eastern University in Philadelphia, USA. It was near there, in Washington DC, that he got into community organising. When he returned home, he worked for a development charity, as a journalist at the BBC and for Bristol’s public health service. He entered the world of politics via the Operation Black Vote initiative.

Hiring help

Mr Rees can’t remember how hard his mum found it to get rehoused on the estate in 1975. But it is more difficult now. There are around 10,000 people on the waiting list for social housing and 300 households in temporary accommodation. House prices, which increased 14% in the year to May, and private rents, 18% up in 2015, are rising faster than almost anywhere in the country, while Bristol has the worst rough sleeping problem outside Westminster.

“This is the flagship crisis in Bristol; not just because of individual family tragedies but because as a city you cannot be viable unless people can [afford to] live there,” he says.

Source: Francis Hawkins / SWNS

The new mayor has appointed former HACT trustee and Ashley Community Housing board advisor, Paul Smith, as his housing lead, to get the city building. He has pledged 2,000 new homes - including 800 affordable - a year by 2020. Yet last year the city built well under 1,000 new homes with only 190 classed as affordable. So, how will he do it?

“We set ourselves a real challenge. We know it’s a stretch.”

Showing a little of his journalism experience and some of his political training, the 44-year-old chooses his words carefully: “We set ourselves a real challenge. We know it’s a stretch. We know the city council cannot deliver that alone. It’s going to take us working with private developers, associations, self-build, community land trusts and so forth.”

But ‘affordable housing’ encompasses myriad products, not all of which are within the budgets of ordinary Bristolians. So what kind of housing does Mr Rees want to build?

“A mix of social rents, council housing as well, making sure there is a mix of part rent, part buy,” he says.

Bristol’s housing tsar

“Our ambition is to get to at least 2,000 properties a year being built by 2020. Obviously if we are going to have a real impact in dealing with the backlog of housing need, then we need to build more than that. We haven’t produced a detailed list of how we will mix those. The planning system is changing radically so we won’t be able to deliver social housing very easily. We want to maximise the number of social housing units we built at social rent. People in Bristol keep telling me that affordable isn’t affordable. So to do that – rather than using the planning system which has been used traditionally – we are going to use our own land to lever in social rents.”

Paul Smith, cabinet member for homes, Bristol Council

Challenging times

Will he build more housing for social rent than predecessor George Ferguson - only four homes last year? Mr Rees suggests so: “If we build 16 in a couple of years, that would clearly not be good enough. We are saying at least 800 affordable homes and that is what we are holding ourselves to.”

He will also have to contend with an unprecedented squeeze on the council’s budget, Brexit and the roll-out of the Housing and Planning Act.

“We are being given a hospital pass by central government.”

Bristol needs to save at least £60m between April 2017 and April 2020, after already cutting £83m over the previous three years. These cuts included £700,000 from housing services and £300,000 from supported housing in 2015.

“We are being given a hospital pass by central government. Here’s all this responsibility we are devolving to you, but by the way here’s less oxygen for you to breath with,” he says.

Mr Rees knows he cannot balance the books without cutting vital services. “People are going to get hurt. And we have to balance the budget within the envelope we have been given. And that’s painful.”

Would he then consider doing what a string of Labour councils did in the 1980s and refuse to set a budget? These councils opposed spending cuts but were eventually defeated by the government. “You have to set a legal budget otherwise you give up power and someone has to come in and do it for you,” Mr Rees accepts.

The Housing and Planing Act also looms large. He admits Pay to Stay, the Right to Buy extension and high-value sales represent a major challenge but says he is exploring with his newly established housing commission ways to protect tenants and social housing stock: “There were a number of propositions about how we can defend our stock from the more negative aspects of that bill.”

Even though he faces a hard battle to make Bristol more affordable, Mr Rees appears to be enjoying his first few months as mayor. Indeed his best moment has been related to housing.

“I felt that vulnerability and we dealt with it.”

“It was about 6.30pm and there was a woman outside with a pushchair, four bags and one suitcase. She was standing outside the advice centre, but it was closed. I saw she was crying, so I went over and said ‘what’s that about’, and she said ‘I don’t know what to do, it’s closed, I’ve got nowhere to go’.

“She’d been staying in the Premier Inn.” Mr Rees called his strategic director, who called the head of housing, who then called an officer - he came down and opened up. “As I picked up her bags to carry them in I heard cutlery clinking around. She had everything with her including her child. An hour-and-a-half later I got a text saying we’d found her somewhere. I thought ‘wow’.”

Mr Rees knows individual acts of kindness cannot solve the crisis he has inherited, but he is pleased he has helped someone who reminded him of the vulnerability he felt as a child growing up on Lawrence Weston.

“You can’t solve every case like that.” He pauses and his eyes fix on the long road that cuts through the estate. “Down here, waiting to catch a bus with my mum at night, I felt that vulnerability and we dealt with it. That’s one of my best moments.”

The sector’s thoughts on Marvin Rees

“I’m picking up more of a partnership approach with housing associations, looking at co-investment, sharing of risk, and putting their land in, which is really critical. They are not being too ideological about it - thinking if we need homeownership that’s fine, if we can use some shared ownership to cross-fund that’s fine.”

Oona Goldsworthy, chief executive, United Communities

“Marvin has appointed Paul [Smith] as his housing lead. He has first-hand housing knowledge, especially of associations. They have the will and clout to get things done, and are receptive to new delivery proposals from potential partners. But his affordable homes target is a tough ask - it’ll take several years to build delivery to this level.”

Nick Horne, chief executive, Knightstone Housing Group

“For me it’s positive so far. Marvin has given Paul Smith the remit for housing. He has helped remove some internal blockages enabling schemes to progress and started a dialogue with associations to increase supply.”

Paul Ville, chief executive, Solon South West Housing

Related stories