You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

How to shift from crisis management to preventing homelessness

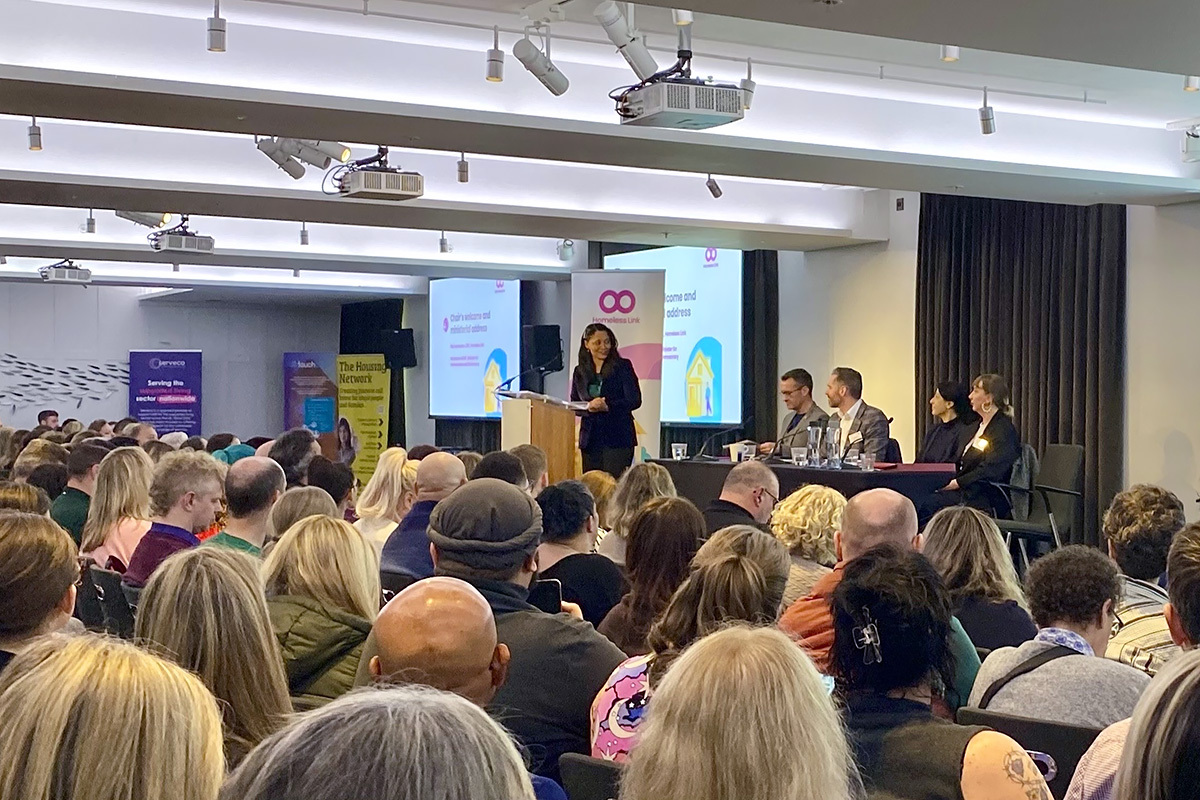

When you are in the middle of a crisis, how do you reinvent homelessness services to make them about prevention? As part of our Reset Homelessness campaign, Jess McCabe reports from a conference where the gap between good intentions and the capacity to change is palpable

![]()

A conference is underway on the fourth floor of the old County Hall, which used to be the home of London’s local authority.

On the stage, Tom Copley, London’s deputy mayor for housing, recalls that when Ken Livingston headed the Greater London Council in the 1980s, he used to put unemployment figures on the roof (where the Conservative government of the time could see them from the parliament buildings across the Thames).

“I don’t know if he ever did the homelessness figures, but if we were to do that now, those numbers would be extremely stark,” Mr Copley says.

Now, a conference venue is squeezed into the grand old building, alongside a Shrek attraction, a hotel and a fish and chip shop. London has changed, but when it comes to homelessness, it feels like the 1980s all over again.

Rushanara Ali, the minister for homelessness, takes the stage for the keynote speech at the Rough Sleeping Conference, which has been organised by Homeless Link, a membership body for service providers. She harks back to her childhood in the 1980s, when some of the frontline organisations in the room were involved in supporting rough sleepers in London’s cardboard cities. She tells the room: “Sadly, here we are again, faced today with the worst housing emergency in living memory.”

Rough sleeping has risen 164% since 2010, the minister notes.

Inside Housing has come to this conference to see if we can learn more about what the next step will be in turning those figures around.

The topic of this conference is ‘Moving from crisis to prevention’. Is the drive or resources there to make such a change? And will the Labour government manage to reset homelessness funding, as Homeless Link and Inside Housing are calling for in our joint Reset Homelessness campaign?

The human cost of the homelessness crisis is high. “I’ve had to step in on a number of occasions to support families who are in really, really difficult circumstances, and in some cases where children’s lives are at stake,” Ms Ali says.

Last weekend, the Local Government Association published data from a survey of councils. This found that a startling one in four will have applied for, or are very or fairly likely to apply for, “exceptional financial support” in the next financial year. Huge temporary accommodation (TA) costs are a key reason for this.

“London boroughs are now spending, collectively, £120m a month on housing people in TA,” Mr Copley says, producing audible gasps even in a room full of people on the frontline of homelessness response.

“Now, if you add that cost up over a year, that’s more than the annual budget the previous government gave us for building affordable homes in London. In fact, you can build the Docklands Light Railway extension to Beckton Riverside and Thamesmead waterfront with the money we spend on TA in London each year and still have change left over.”

“The proof will be when a homeless strategy comes out – how ambitious is it? If it’s tinkering around the edges and easy stuff that doesn’t cost any money, then we lost the moment”

So far, so completely unsustainable. Or, as Rick Henderson, chief executive of Homeless Link, puts it after Mr Copley’s speech: “£120m – what we could do with that!”

The question, then, is what needs to change? Can some of this money be redirected to stop people becoming homeless in the first place, and how much is the government going to be able to achieve when the news agenda is full of stories about departmental budget cuts?

Ms Ali wasn’t giving much away on what to expect from the Spending Review in June, though she acknowledged the need for longer-term funding settlements, which may have gone some way to reassure the service providers in the room.

Mr Copley said: “From my perspective, the GLA [Greater London Authority] perspective, it has been like night and day since the change of government last year.”

For service providers, there is a cautiously optimistic vibe.

On the sidelines of the conference, Inside Housing sat down with Emma Haddad, chief executive of charity St Mungo’s.

How is St Mungo’s finding the new government? Ms Haddad is upbeat as she says: “I’m still trying to be hopeful. I think we have to be. We have to give people a chance. We want to work together.”

Ms Haddad is on the government’s panel on homelessness and rough sleeping, which provides advice to ministers, feeding into a new strategy that is being developed. What is the inside story on the expert group?

“They tasked us all to go off and do some work and bring it back. That’s hopefully going to find its way into the strategy,” Ms Haddad says.

“The language and the mood music are still right. It’s about prevention, about making things more sustainable, ending homelessness, not just rough sleeping. All of that is good. I think [a strategy] has just got to come soon-ish, otherwise we might run out a little bit of staying hopeful.

“I think the proof will be when a homeless strategy comes out – how ambitious is it? If it’s tinkering around the edges and easy stuff that doesn’t cost any money, then we kind of lost the moment, I think. I’m hoping it’s going to be ambitious.”

On the plus side, she says, “there’s a shared sense of hope in that room”.

“An exemption to the increase in employer National Insurance Contributions was just never on the table”

In the meantime, though, homelessness services are at their limit.

While St Mungo’s and the sector at large welcomed announcements on funding top-ups for homelessness and councils, frontline organisations have been struggling with the impact of the rise in employer National Insurance Contributions (NICs) announced in last autumn’s Budget.

For St Mungo’s, the cost of this was roughly £2m a year. For services the charity runs for local authorities, it tried to go back to councils for an uplift to cover the cost.

The Budget also gave councils a roll-over of one year’s homelessness funding, which was meant to tide them over until the homelessness strategy could be finalised. New funding was expected in the Spending Review. But this roll-over funding didn’t include any increase, so St Mungo’s hasn’t been able to renegotiate these contracts to account for NICs. As a result, “you have to try and reshape your service and cut posts, and that’s delivering a reduced service”, Ms Haddad says.

St Mungo’s, along with others in the homelessness sector and care providers, was advocating for an exemption to the increase. “It was just never on the table,” Ms Haddad says.

These cost pressures leave little capacity for changing or improving homelessness services, or – the subject of the conference – moving from crisis to prevention.

Yet Ms Haddad is convinced that, without a shift to prevention, the current crisis will continue to spiral out of control.

One problem is that while moving to prevention saves the government money, you have to spend more in the short term. “If you properly want to move the system to prevention, you can’t just totally switch off the tap on funding crisis response, right? There’s got to be a transition,” she says.

But how easy will it be to extract extra funding from the Treasury in the current climate? On the other hand, can the government afford not to make this investment, given the impact of rising homelessness on council finances?

St Mungo’s runs London’s No Second Night Out project. With funding from the GLA and the government, it has been piloting two projects.

One is a rough-sleeper prevention pilot, which provides specialist, on-site move-on support to people who are at imminent risk of becoming homeless.

It is also working with Sir Sadiq Khan, the mayor of London, on an ‘ending homelessness hub’. The plan is that the current No Second Night Out programme will transition into a series of such hubs, which have a much greater focus on prevention. This is being worked up by the GLA at present, as part of the mayor’s target to end rough sleeping in the capital by 2030.

In her speech on the stage of the conference, Ms Haddad spoke about some of the findings so far. “When we intervene and support people before they have to sleep on the streets, they have generally lower support needs.”

This is because, she explains, they haven’t experienced the trauma of sleeping rough. They haven’t been at risk of being attacked, or felt the impact on their physical and mental health.

“When we support people before they arrive onto the streets, we have found that it’s more likely we’ll be able to help them move on to private rented sector accommodation,” she says. This means they were less likely to need to go into supported accommodation, which is more expensive.

“If numbers [of homeless people] keep increasing month for month, then we’ve clearly got it wrong”

Under No Second Night Out, support in London generally is only accessible if someone has been “verified” as sleeping rough on the streets, meaning they have to sleep rough at least one night. This is both traumatic for the person concerned and leads to higher support costs. Ms Haddad garners applause from the room when she says this system should end.

Later, I ask what would be a sign of the government succeeding on homelessness. “If numbers [of homeless people] keep increasing month for month, then we’ve clearly got it wrong. We’ve got to reverse the trend. Or even stabilise it, and then gradually bring it down,” she says.

In December, Homeless Link published a new report which highlighted the black box of government spending on exempt accommodation for people experiencing homelessness. This supported-housing provision has been the subject of repeated investigations into the quality of what’s provided. And, Homeless Link said, it’s not even possible to accurately track how much the government is spending. Could this be a source of funding for prevention work?

Ms Haddad demurs to comment directly on exempt accommodation, but says: “I think, in general, we’ve got to really challenge ourselves on where the money’s coming and going. And if it’s not having a big enough impact, or maybe a big enough impact on a big enough number of people, then maybe it needs to be rediverted.”

In the break, I get talking to a conference attendee from a large combined authority.

They tell me that homelessness staff at the councils in their area wouldn’t even have time to come to a conference like this, given how overstretched resources are.

On the main stage, the biggest response is to Jess Turtle, who spoke about her experiences as co-founder and co-director of the Museum of Homelessness.

“Apparently, there’s a moment in politics where we might be able to make some change,” she says. “So let’s do it.”

Recent longform articles by Jess McCabe

A night shelter for trans people struggles to find funding

Jess McCabe reports from The Outside Project’s new transgender-specific emergency accommodation, as it prepares to open its doors. Why is this accommodation needed, and what has the organisation learned from almost a decade of running LGBTQ+ homelessness services?

Reset Homelessness: ‘The system cannot continue as it is’

Inside Housing and Homeless Link’s new campaign, Reset Homelessness, calls for a systemic review of homelessness funding in England. But how has spending on the homelessness crisis gone so wrong? Jess McCabe reports

A day on site with MTVH’s new chief executive

Jess McCabe spends the morning with Mel Barrett, Metropolitan Thames Valley’s new chief executive, touring its flagship regeneration project in south London. In his first major interview, he talks through his early plans for the association

Overcrowded and on the waiting list: the family housing crisis and what can be done to solve it

Within the housing shortage, one group is particularly affected: families in need of a larger home. But how big is the demand? And how can building policy and allocations change, to ease the problem? Jess McCabe investigates

Who has built the most social rent in the past 10 years?

Jess McCabe delves into the archives of our Biggest Builders data to find out which housing associations have built the most social rent homes

Biggest Council House Builders 2024

For the second year running, Inside Housing names the 50 councils in Britain building the most homes. But is the rug about to be pulled on council development plans? Jess McCabe reports

Inside Housing Chief Executive Salary Survey 2024

Inside Housing’s annual survey reveals the salaries and other pay of the chief executives of more than 160 of the biggest housing associations in the UK, along with the current gender pay gap at the top of the sector. Jess McCabe reports

Sign up for our homelessness bulletin

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters

Related stories