You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

What would a ‘nature-centric’ approach to housebuilding mean for the UK?

Instead of treating nature as something separate to us, like a property we have a right to destroy, we can reassess our relationship to it, writes Matthew Pritchard, co-lead for the Nature-Centric Catalyst at the University of Reading

You might not realise it while out in our beautiful countryside, but the UK is one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world.

According to UK government reports, nature losses drive human losses, from increased risks of flooding to food insecurity, disease and pollution. Wildlife decline also contributes to human physical and mental health decline.

How, then, do you build 1.5 million new homes in five years without making matters worse? Given our lack of affordable housing, the UK government is in a hurry to build as many homes as possible. Assuming this brings house prices down (which isn’t necessarily a given), how can it square the circle?

To date, the government has variously blamed bats, newts, spiders and snails for blocking developments – species that all happen to carry a tinge of witchcraft. As Tony Juniper, chair of Natural England, noted at the recent Wild Summit, ministers have been less vocal about the obstructive behaviours of popular creatures such as otters or golden eagles.

Cynical rhetoric notwithstanding, environmental protection policies, and their implementation, are failing: the government is falling short of its own targets for nature recovery, and for providing clean water and air. It remains on track for just nine out of 43 environmental commitments.

Take, for example, the policy of biodiversity net gain. This outlines how much habitat needs to be “restored” in exchange for developers destroying nature to build homes, but it turns out that the promised nature restorations rarely happen. Doubling down on this approach, the new planning system reforms enable developers to pool promised habitat “units” and restore them elsewhere.

“Destroying nature in one place and trying to rebuild it elsewhere isn’t the answer”

But destroying nature in one place and trying to rebuild it elsewhere isn’t the answer: ecosystems take decades to mature (consider the complex interactions between soil fungi, plants and insects), and people living in new homes surrounded by dead zones will pay the price of drastically reduced health benefits.

Because existing approaches aren’t working, my academic research explores how society might become “nature-centric” – assigning inherent value to other creatures, rather than objectifying them as lifeless “assets”.

Seeing nature as an intrinsic part of us, and vice versa, is a more scientifically accurate worldview, and is essential for protecting our environment. This thinking has widespread implications for the design of our businesses, governance and education systems.

It’s a worldview shift that organisations including the UN and the European Environment Agency deem essential for a sustainable civilisation. Last year, an international science body produced a report ratified by 147 governments, including the UK.

The conclusion identified “disconnection from and domination over nature and people” as one of the main causes of global biodiversity loss, and stated the need for “fundamental system-wide shifts in views, structures and practices”.

In a housebuilding context, it means asking what other beings already have their homes in the proposed area, and then seeking to live alongside them. Instead of treating nature as separate to us, like a property we have a right to destroy, we can reassess our relationship to it.

This is not some impractical ideal. Many nature-centric housing developments already exist, including in Brazil, Italy and the Netherlands. There may be challenges in building them at scale and adapting them to local ecosystems, but examples show that housing design and surrounding areas can be tailored to help regionally rare animals like otters and certain bats, as well as amphibians, insects and plants.

I recently helped to run a workshop with experts from law, urban planning, architecture, garden design and housing policy. They agreed that the technical expertise already exists, but that we lack the deeper mindset shift needed to bring about such an ambitious programme.

“Building these homes may take longer than a single parliamentary term, but anything less will continue to drive the loss of nature on which our health and prosperity depends”

Research shows that promoting this nature-centric shift in worldview must become a top priority. Without such realigned value systems, environmental regulations are simply rules that get ignored. Hence, the poor state of our rivers and the loss of our plants and wildlife.

In a planning context, the key challenge is to expand our imaginations for how we can live alongside other species, and build political courage to make these developments a reality. Building these homes may take longer than a single parliamentary term, but anything less will continue to drive the loss of nature on which our health and prosperity depends.

We cannot build 1.5 million homes with a casual attitude to other life. The real solutions to the housing crisis transcend bricks and mortar and rules about where to put them: we need to rebuild our care and responsibility to the natural world, acknowledging nature as something we humans are deeply involved in.

To solve the housing crisis in ways that are genuinely sustainable may require “inner development”, but that development is highly rewarding in itself. Moreover, it consigns to history the annihilation of local populations based on weak promises of developing related ecosystems elsewhere, and instead builds a future of healthy, ethical and desirable homes.

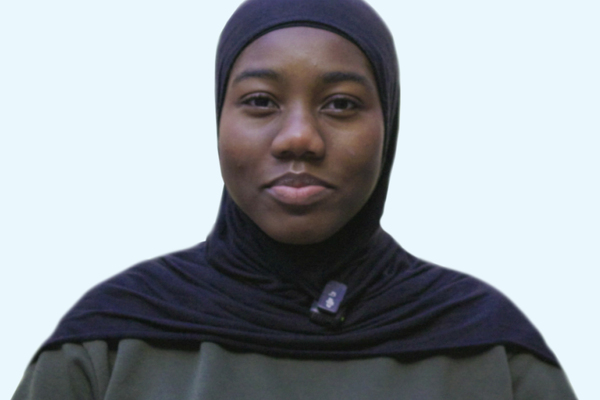

Matthew Pritchard, co-lead for the Nature-Centric Catalyst, University of Reading

Sign up for our development and finance newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters

Related stories