You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

60 years on: the story of the Race Relations Act 1965

This Black History Month, Inside Housing looks back at the Race Relations Act to consider the legacy of the first anti-racism law in England. Was it a “toothless” gesture, or the first step towards true equality? What did it mean for housing – which was initially not included in the new anti-discrimination legislation? Samir Jeraj reports

Sixty years ago, a Labour government was facing pressure to restrict migration. Race relations were at a low point following a series of race riots over the preceding years, protests against discrimination and a shock 1964 election defeat in Smethwick, where Conservative candidate Peter Griffiths defeated the incumbent Labour MP using the slogan “if you want a n***** for a neighbour, vote Labour”.

Harold Wilson’s government came to power in that 1964 election, with a manifesto promise: “A Labour government will legislate against racial discrimination and incitement in public places.”

It was a bold commitment, the first legislation against racism in British history. But it sits uncomfortably with the next sentence: “Labour accepts that the number of immigrants entering the United Kingdom must be limited.”

The Race Relations Act was passed and came into force 60 years ago this November. Its aim was to tackle the racism that had grown in the post-war years. Today, its legacy and impact is contested, particularly its impact on housing discrimination – but its lessons are important for our present-day struggles against racism.

For critics, the 1965 Race Relations Act was an ineffectual sop, not extended to the main areas of discrimination in employment and housing, and just a way of looking tough on racism while doing little to tackle it. At the same time, Labour was continuing and expanding anti-migrant policies begun under the Tories to restrict “Commonwealth immigration” under the 1962 Commonwealth Immigration Act.

For supporters, the 1965 act was the first piece of anti-racism legislation in Britain, following years of unsuccessful bills from backbenchers, the result of campaigning and the serious engagement of the Labour Party and its leadership with an issue that played poorly with much of its electoral base. It also set the precedent, continued up to and including the 2010 Equality Act, that discrimination in goods and services is an issue of civil law and not criminal law.

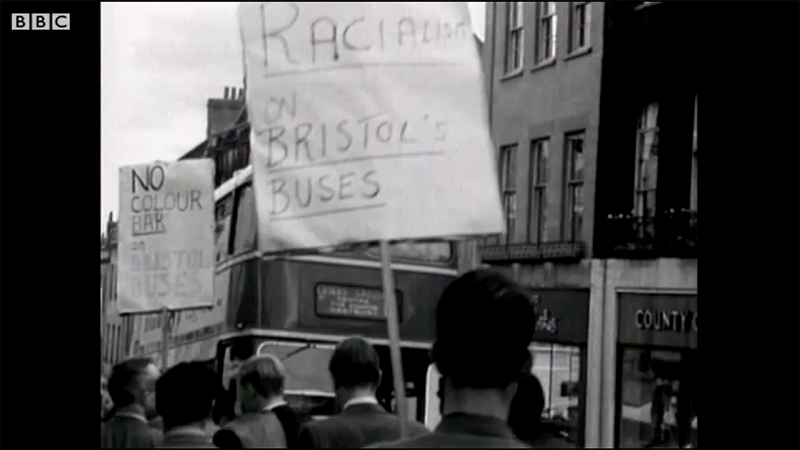

Labour’s political strategy in the 1960s was to combine further controls on immigration with action against racial discrimination in the UK. Mr Wilson was influenced by the 1963 Bristol bus boycott, while he was still leader of the opposition. This local campaign led by the West Indian Development Council successfully got the council-owned bus company to end its policy of only hiring white people. Mr Wilson reportedly sent a leading campaigner in the bus boycott, Paul Stephenson, a personal telegram to express his support and promise a change in the law.

The 1965 act had two main elements. First, creating a criminal offence of incitement to racial hatred, designed to counter the activities of Oswald Mosley and his supporters, and to respond to the race riots of the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Second, it outlawed discrimination in public places (including pubs, clubs and public transport) and, following lobbying by the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD), established a ‘Race Relations Board’, whose purpose would be to provide conciliation.

The direct impact of the 1965 act was limited by the fact that it was restricted to discrimination in public places. The main areas of everyday discrimination – employment and housing – were not covered, and it remained legal for employers and landlords to say “no coloureds”. A 1966 BBC documentary filmed in Smethwick found that immigrants were barred from housing, local barbers would refuse to cut the hair of “coloured” people, and even churches closed their doors to fellow Christians who were not white.

“It was groundbreaking in many ways,” says Jabeer Butt, chief executive of the Race Equality Foundation, which works on race equality in housing, health and social support. “It was a recognition at a political level of some of the [racist] experiences migrant communities had experienced.”

He adds that the research the board commissioned on racial inequality in housing was vital in highlighting discriminatory practices, such as ‘sons and daughters’ policies, which prioritised people born in the area for council housing.

Khalid Mair, chair of Imani Housing Co-operative, tells Inside Housing he believes that the specific focus on race equality in the 1965 act and subsequent legislation was important. “There’s still a need for a separate focus on race, because the stats bear up to the challenges that are out there,” he says. Mr Mair also runs SHARP, a social housing anti-racism pledge that provides a quality assurance framework to help housing organisations work towards becoming anti-racist.

At its start, the Race Relations Board had no powers of enforcement and its limited scope meant 70% of the race discrimination complaints it received were outside its remit. By 1968, it had referred only four cases to the Attorney General, the ultimate authority under the law, whose only recourse was to seek an injunction against further discrimination through the county court. No cases ever reached this far.

Vishnu Sharma, an activist with the Indian Workers’ Association, described the board as “toothless”, while Ambalavaner Sivanandan from the Institute of Race Relations said it was not just toothless, but “gumless”.

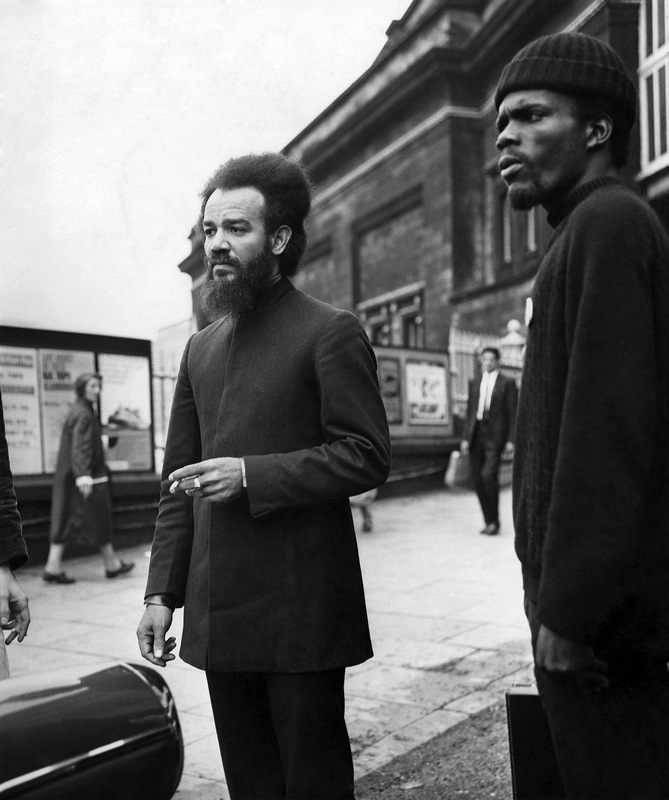

The first person to be prosecuted under the act for inciting racial hatred was Michael de Freitas (aka Michael X), a Black power activist (and a former enforcer of slumlord Peter Rachman). The following year, Colin Jordan, leader of the British National Socialist Movement, was convicted and sentenced under the law to 18 months in prison, claiming afterwards that he was fighting to “save my country from Jewish control and coloured immigration”.

Campaigning groups such as the CARD lobbied for tougher laws, deploying student volunteers in 1966 to expose discrimination in housing and factory jobs. Black or Asian students would be paired up with white students and would each apply for a job, credit or housing to see who would be successful. More than 150 separate complaints of racial discrimination were filed by CARD with the Race Relations Board, but 90% of them were outside the scope of the law.

The Race Relations Board itself asked for its remit to be extended to housing and employment. It commissioned quantitative data on discrimination collected and published in 1967 by Political and Economic Planning (known as the PEP report) and a review of anti-discrimination legislation, known as The Street Report, published in the same year.

Sir Geoffrey Bindman, legal advisor to the Race Relations Board and a prominent human rights lawyer, later said: “Timidity and pressure to compromise with fierce political opposition denied its application to employment and housing where discrimination was much more widespread and damaging.”

The failures of the 1965 act led to subsequent legislation in 1968 to extend anti-discrimination law to housing, employment and other private services such as credit. And in 1976, another Race Relations Act replaced the Race Relations Board with a stronger Commission for Racial Equality, and placed a duty on public bodies such as councils to promote race equality, which had a tangible impact on services.

“There was more infrastructure and more resources around supporting communities in terms of looking at issues of culture and cohesion,” Imani’s Mr Mair recalls. “When people talk about ‘we’re a proud multicultural society’, I think in the ’70s and ’80s we had the resources to promote that thinking,” he adds.

However, Labour’s imperative to reduce migration carried on in parallel, and in 1968, the same year that discrimination in housing became illegal, the Labour government downgraded the passports of British citizens who did not have a parent or grandparent born in the UK, in a deliberate move to restrict “coloured immigration”.

Racial inequality persists

Sixty years later, racial inequality is still an everyday fact in housing and employment, and public life. Although landlords can no longer advertise “no coloureds”, in practice it is still very possible to discriminate against tenants. A 2024 study by Heriot-Watt University showed that Black people in the UK are four times more likely to be homeless and less likely to access social housing compared to white people.

The part of the 1965 act that criminalised inciting racial hatred continues to have an important impact on punishing violent racist speech, recently including the distribution of neo-Nazi material, but is struggling in the age of social media.

Racial inequalities persist in health, criminal justice and education, and the Windrush scandal demonstrated that the link between policies on migration and their impact on race equality is still very much with us. So too are questions over whether the Equality and Human Rights Commission, the investigation and enforcement agency since 2010, is effective at pursuing and tackling discrimination.

In Labour’s 2024 manifesto, the party pledged a Race Equality Act to tackle pay and other racial inequalities, and it seems likely that a mandatory race and disability pay gap will be introduced following a government consultation. But the debate on migration seems to have moved on little, despite decades of the UK as a multicultural society.

For Mr Mair, the sector should be prompted to explore how housing discrimination still affects Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities, as well as migrants.

“All the stats are there in relation to homelessness and poor-quality accommodation,” he says. “I think reflecting on the Race Relations Act is a poignant opportunity for these discussions to take place.”

And for Mr Butt, the 1965 act left a problematic legacy that we are still living with. “Ever since that [act], both the main parties constantly associated the two: that we can’t progress race equality without then also controlling how many immigrants we have in this country. Unfortunately, the current debate has almost forgotten racial inequality, but instead is focusing on controlling immigrants.”

Sign up to our Best of In-Depth newsletter

We have recently relaunched our weekly Long Read newsletter as Best of In-Depth. The idea is to bring you a shorter selection of the very best analysis and comment we are publishing each week.

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters.

Related stories