You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

A national framework for recovery and resilience: why ‘levelling up’ will not be enough

Housing association Bolton at Home has teamed up with Inside Housing to publish its emerging research about what the future role of social landlords should be as the UK recovers from the pandemic and what its findings mean for associations, councils and other local partners, and central government and the levelling up agenda. In the second article in the series, researchers Ian Ankers and Brendan Nevin explore the implications of November’s Spending Review on the future shape of society

The economic shock which has emerged from the international public health crisis stemming from the pandemic has produced a decline in economic activity of historic proportions.

The chancellor confirmed that the economy is expected to contract by more than 11% this year, the largest annual contraction in 300 years. The public sector deficit which has emerged is likely to be £400bn or 19% of GDP in 2020/21. This reflects the extent of financial support required in the emergency phase which was needed to stave off economic collapse.

In this context the fiscal event on 25 November provided the first iteration of the investment framework which will propel the UK into the repair, recovery and resilience building phases which must follow the emergency as we slowly emerge into the post-pandemic world next year.

The Spending Review confirmed that the government intends to deploy the largest public sector capital investment programme since the 1970s. In the four years to 2024/25, £429.6bn is available to spend on infrastructure, land and the environment. Transport and the zero-carbon agenda are big winners in the resource allocation process, with the latter being the first large down payment in a generational shift in investment priorities.

Aligned with this increase in the volume of investment there were also spatial policy shifts which signalled a shift in investment towards the Midlands and the North, after four decades of relative decline.

Investing in the ‘levelling up’ agenda is significant because it explicitly recognises that addressing spatial inequality is now a major policy priority and it could be a powerful tool to stimulate recovery in the most impoverished parts of England. It is also important because it implies a standards based framework will be developed which gives meaning to the term and develops a policy which could drive forward improvements in the resilience of areas which have experienced endemic infection levels over the first and second waves of the pandemic.

There are three key component parts of the levelling up agenda which are designed to narrow the stark divisions between regions, town and cities in England. The first is the National Infrastructure Strategy which sets out how the capital programme will be directed. The prime minster in his foreword strikes a reassuring tone for the most deprived localities

“…in the period covered by this strategy, we will significantly shift spending to the regions and nations of the UK. On our major A roads and motorways, two-thirds of our upgrades are outside south-eastern England, including duelling the A303 to the south-west and completing the first trans-Pennine dual carriageway in 50 years”[1]

Secondly the programme contains a bespoke levelling up fund, which has cross-departmental support and can be used flexibly to achieve local objectives.

This £4bn fund is for capital expenditure-only investment in small-scale infrastructure projects in the next four years in “neglected” areas in England.

The third contribution to achieving more equal social and economic outcomes was the review of the government’s Green Book. Many organisations in the North and the Midlands have long contended that the Green Book, which sets out an appraisal methodology for capital projects, favours investment in high-value (largely southern) areas of England because the financial benefits of investment are skewed by land value uplift. This also works against areas which face expensive reclamation challenges where the land may have a negative value.

The Treasury has largely dismissed this critique but consider the reliance on financial benefits and costs to be the result of inadequate specification of outcomes and their relationship to government policy objectives in the business case which frames the appraisal.

The policy priority now given to levelling up, it is argued, should help release investment in more disadvantaged low-value areas if the business case and outcomes are aligned with this government priority. The problem with this currently is that the levelling up programme does not have any clearly defined policy priorities, KPIs or measurable objectives to input into the Green Book Business case. It is currently an ill-defined policy without a transparent strategic framework.

While the headlines in relation to redistribution look reassuring, there are several issues which emerge when closer scrutiny is applied to the emerging framework. The prime minister highlights that two-thirds of new road schemes are to be located outside the South East. However, these areas contain 67% of the English population, so presumably levelling up is related to the number of projects being proportional to population in this case.

However, new schemes do not necessarily translate proportionately into investment. They can be large or small.

Furthermore, the point made avoids referring to existing spending commitments, which are substantial. There is good reason to believe that this parliament will oversee another disproportionate investment in the South of England. This is because massive and multifaceted 30-year development programmes in the Thames Estuary and the Oxford/Cambridge/Milton Keynes Arc have already been developed by, and incorporated into, the machinery of government. The North has no such concepts at delivery stage or the capacity to develop them as a result of austerity and previous government policies which provided no incentive to invest in the development and delivery of large schemes.

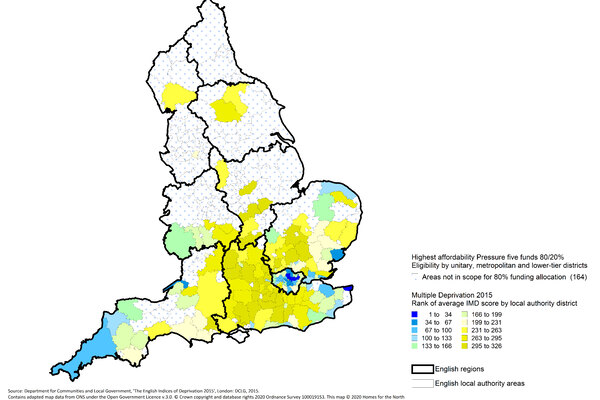

A further additional problem in relation to developing a levelling up strategy which can provide a platform for the pandemic recovery relates to the continued in-built discrimination against the poorer areas of England in the Midlands and the North. Homes England are mandated by government to allocate 80% of the multibillion funding for land and infrastructure spending to areas which have higher property and land values.

This government rule produces a skew in investment to more prosperous local authority areas south of the line between the Humber and the Severn and no deprived area in the North of England has a priority (see map one below). There is some potential to use the new levelling up fund for small-scale infrastructure provision, but this approach has some serious limitations: it is allocated by a national competition; bids are usually limited to £20m per project; and it has a short-term focus to 2024/25 and therefore cannot replicate the 30-year view possible in the South and the East of the country.

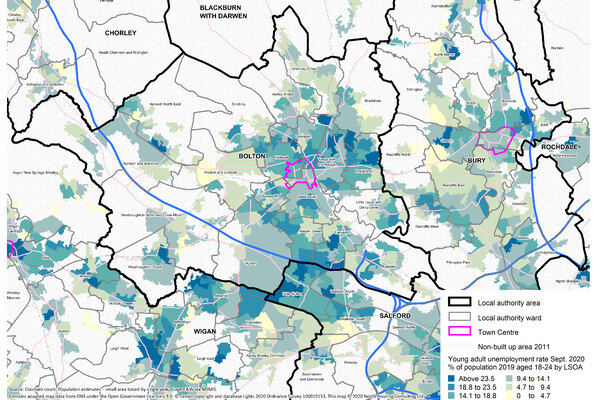

The levelling up framework is still undefined and Is not tied into objectives and a national strategy and therefore will not deliver fast enough. The mounting urgency is evident in a place like Bolton where Universal Credit claims increased by 84.6% in the period from January to September.

The economic collapse is having catastrophic impacts on the young, with unemployment rates already over 30% in some areas (see map two below).

Areas in the North and the Midlands need three responses right now and these are: a capacity development fund to allow localities to develop the skills and delivery vehicles that can work up large-scale, multi-faceted schemes and programmes and address the wide-ranging social and economic weaknesses which COVID-19 has exposed. This should be supported by an empowerment fund which can facilitate participation by all communities in the local response to the pandemic.

Finally, areas which have been worst impacted need to address multiple problems of continuing ill health, almost certainly with an aftershock of serious mental health issues which accompany disasters. The economies needed rebuilding before, and this is an even more pressing issue now, while housing standards in the existing stock in some locations are unacceptable.

Over time interventions will have to be supported by a national investment framework which is standards driven, but a response is needed right now which can provide a bridge from the disaster to long-term recovery. A flexible and devolved pandemic recovery funding programme is needed which can target resources dependent upon the priorities of local communities. In some places that could be emergency food provision, a focus on youth unemployment and the revival of the town centres – other areas may have different priorities.

What is striking about the November fiscal event is that the statement and subsequent proposals gave no sense of urgency in addressing the aftermath of an international public health disaster.

This disaster in the UK has been exacerbated by inequality and a historic lack of standards driving the development of public policy, which in turn has diminished the resilience of the poorest communities and places. Rather than rethink and reflect on how we have arrived at such poor health and economic outcomes in the UK, the response to disaster is being addressed through a series of largely economic and silo-based interventions designed in Whitehall before the pandemic arrived.

Levelling up when fully developed and reflective of local priorities, with an accompanying multi-parliament timeframe, can make real impact for the most distressed places. This, however, will not be sufficient and our next article will look at the types of cross-government policy reforms needed to deliver a more resilient future for England’s poorest places.

Brendan Nevin, director, North Housing Consulting; Ian Ankers, executive director of business development, Bolton at Home

[1] HM Treasury (2020) National Infrastructure Strategy: Fairer, faster, greener; HMSO November 2020

Sign up for our Week in Housing newsletter

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters