You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Latest housing research: Is the social housing allocation system failing those most in need?

A new report uncovers how systems and processes for allocating social housing at a local level vary substantially, and suggests possible solutions, writes Richard Hyde, chair of the Thinkhouse Editorial Panel

Thinkhouse is a website set up to be a repository of housing research. Its editorial panel critiques and collates the best of the most recent housing research.

In December, the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE), Crisis and Heriot Watt University released Moving the deckchairs? Social housing allocations in England.

While only a short paper on the current flaws in the allocation of social housing in England, the quality of analysis is excellent, shedding light on a system that isn’t widely reported on but can have a profound impact on those who need a safe and secure home.

Local authorities have considerable discretion over how they allocate their social housing stock, provided the allocation scheme gives some preference to statutorily prescribed categories.

These include people who are homeless; those with a particular need for accommodation on medical or welfare grounds; people in unsanitary, overcrowded or unsatisfactory housing conditions; and people who need to move to a particular local authority area to avoid hardship.

The Localism Act 2011 also gave local authorities freedom to specify classes of people who are, or are not, qualified to access the social housing waiting list in their area. Many councils took this opportunity to remove significant numbers of applicants from their housing registers.

Housing associations, provided they take account of need and let homes in a fair, transparent and efficient way, also have a degree of flexibility for setting qualification criteria for access to their housing registers.

Local authority and housing association allocation systems can be combined in a wide variety of ways. Therefore, the systems and processes for allocating social housing at the local level vary substantially.

The report presents evidence that areas in England where there was a strongly harmonised system, implemented through a common allocations policy and/or a common housing register across local authorities and social landlords, operated more efficiently and effectively.

Examples of this included the use of collaborative agreements and partnership work to address arising issues in relation to minimising voids across the portfolio of stock and nomination refusals.

In contrast, where stock was spread out across multiple providers without agreements in place, there was less harmonisation of approaches, and frustrations were expressed in relation to housing management and maintenance of homes.

Removing obstacles

Greater harmonisation and good background information leads to fewer refusals by housing associations of local authority nominations. The report recommends some practical policy changes that will help remove disadvantages for those who need a home but have to deal with an uncoordinated and dysfunctional allocation system.

First, local authorities should regularly maintain and update their housing registers, including data-sharing consent, checks on affordability and eligibility, and support to address any issues that might prevent applicants being offered a home.

There should also be processes in place where housing associations and local authorities can share information to inform local housing need assessments. This should draw on data from the housing register and should monitor reasons for lettings being refused.

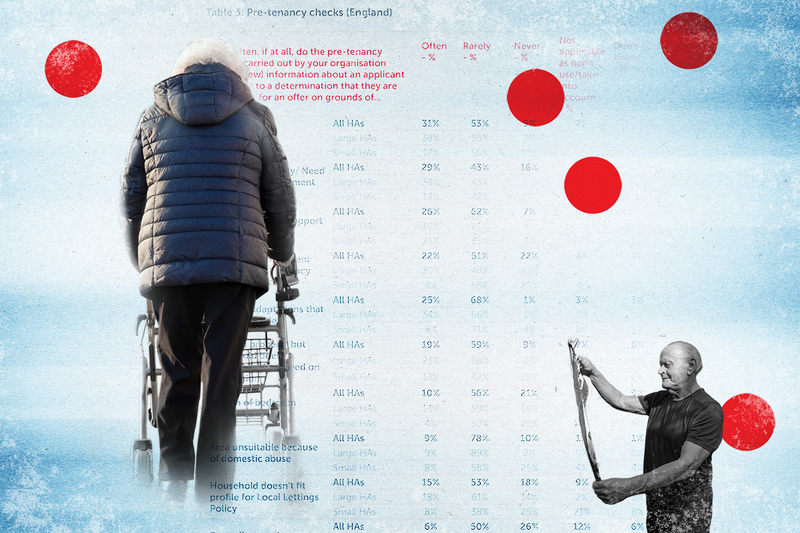

Working within the UK’s data protection regulations, local authorities need to share more information on the circumstances and needs of households applying for social housing while experiencing homelessness. This should mean housing associations have to undertake fewer pre-tenancy checks and should lead to faster, more suitable allocations.

Housing associations need to share information on any refusals so that they can work with local authorities, applicants and other housing associations to overcome barriers to accessing social housing.

Leaving no one behind

The report then moves on to look at how the allocations support (or fail to support) all those who need social housing, and particularly those on low incomes.

While the lack of supply of new houses, including three-bedroom or larger houses, is critical, housing benefit restrictions and the benefit cap mean that more affordability checks are having to be done by housing associations. This can lead to prospective tenants being turned down for properties that were deemed financially unviable for them even if they were otherwise suitable.

As a result, they are faced with the stark reality that they may not be able to afford any housing at all. The report argues that these issues were compounded by the post-Covid cost of living crisis.

The crisis has also had wider implications for housing associations’ business models and resources. The increasing cost of fuel and building materials impacts housing associations’ running costs, which might mean future rent rises for their tenants, whom stakeholders are acutely aware have their own struggles with rising prices.

“If households cannot afford social housing, they are unlikely to be able to afford any housing at all, and likely will consume more costly public services”

The report argues that action is needed at several levels on this critical issue: if households cannot afford social housing, they are unlikely to be able to afford any housing at all, and likely will consume more costly public services. It recommends that the welfare system ensure that homes, and especially social homes, are affordable.

The UK government should review the interaction between social housing rent levels and social security arrangements to ensure that no household entitled to mainstream social security benefits is unable to afford a social home of an appropriate size to their needs.

The report also says the UK government should direct the Regulator of Social Housing to establish requirements in the Tenancy Standard preventing exclusions on the grounds of low income. This should include provisions to ensure requirements such as rent in advance and financial viability checks are not used as a barrier to social rented housing for people on low incomes.

The government should also direct the regulator to identify the steps taken by housing associations so as not to exclude applicants based on affordability checks, and to provide support enabling applicants on the lowest incomes to access social homes. This should be included as recommended practice in its code of practice guidance to registered providers.

Local authorities and housing associations should remove minimum income requirements from the eligibility criteria for access to their housing register or waiting list, and should ensure that their pre-tenancy processes prioritise supporting people into sustainable tenancies rather than informing decisions about whether to allocate the tenancy.

So, while readers are left in no doubt that the answer to the question of whether social housing allocations are failing those most in need is a resounding “yes”, they are also provided with possible solutions. If these are not grasped by policymakers, we will continue as a nation to have a housing system that discriminates against the very people it was designed to help.

Richard Hyde, chair, Thinkhouse Editorial Panel

Sign up to Inside Housing’s Daily News bulletin

Sign up to Inside Housing’s Daily News bulletin, featuring the latest social housing news delivered to your inbox.

Click here to register and receive the Daily News bulletin straight to your inbox.

And subscribe to Inside Housing by clicking here.

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters.

Related stories