You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Social rent: still a big part of landlords’ plans

Inside Housing’s Top 50 Biggest Builders survey showed contrasting approaches to social rent. Mark Smulian speaks to several landlords to find out why the tenure is still part of their growth plans. Illustration by Ben Kirchner

Virtue or necessity? There are landlords that build unusually high proportions of homes for social rent among their completions, and for some there will be the warm glow of doing the right thing for people in need by providing homes that are cheaper than the 80% of market rate ‘affordable’ category.

For others, there will be the cold realisation that if they want to build in some areas, Section 106 planning gain agreements force them to build for social rent. This happens even when their own business plans suggest something else would be better, since they cannot get grant for social rent – unlike for the affordable rent model.

Section 106 deals are those struck by councils and developers, normally covering the provision of affordable housing and site-specific infrastructure.

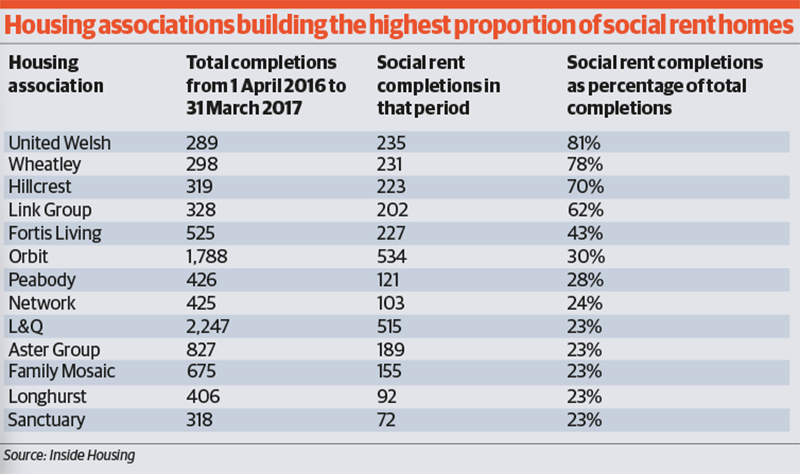

Last month, Inside Housing’s Top 50 Biggest Builders survey showed the top 10 landlords for completions for social rent. Things notably changed, however, when looking at the number of homes for social rent built as a proportion of a landlord’s overall completions.

Regional boom

The four landlords with the highest proportions of social rent among their developments all operate in either Scotland or Wales: United Welsh, Wheatley, Hillcrest and Link Group. This is perhaps unsurprising because landlords in those countries can still access grant to build for social rent, unlike in England.

Richard Mann, group director of operations at 5,650-home United Welsh, which built 81% of its 289 homes in 2016/17 as social rent, explains: “In practice, in Wales rents are based more on local income levels than a proportion of market rents, as in England. Councils have followed that and their planning policies are in line with it.

“If you look at councils’ local development plans, you will see that they are designed so that developers provide homes that can be rented at what the Welsh Government considers a social rent for the area.”

Mr Mann worked in England earlier in his career and says Wales’ ‘acceptable cost guidance’ for social rent is similar to the ‘scheme cost indicator’ used by the former Housing Corporation, so that “say, if a two-bedroom house cost £100,000, grant applications would be made against the overall value of the land and build cost so you could charge a social rent.

“That system has been retained in Wales and, because the housing market here has recovered nicely, there are lots of developers working and the local authorities have been pretty robust in insisting through their planning policies that they provide homes that can be charged at a social rent.”

Click here for detailed, interactive tables of findings from our Top 50 Biggest Builders survey

He says the acceptable cost guidance system means “local development plans are clear that developers have to provide homes on which a social landlord can charge a social rent and I think what we have here is better than in England, where rents went up and they now have the [1% rent reduction], which has upset a lot of business plans”.

In Scotland, the Scottish Government provides grant for mid-market rent – similar to the social rent category in England – with initial rents no greater than the Local Housing Allowance of the area concerned.

David Zwirlein, director of development and new business at 5,602-home Hillcrest in Scotland, says the group uses its subsidiary company Northern Housing to deliver this rent product. “Due to the varying levels of Local Housing Allowance in different areas where we develop, mid-market rent is not always financially viable, although there is a demand for this tenure,” he says.

“In areas of high local housing allowance, we develop 25% of our programme for mid-market rent compared with little or no provision in areas with low levels.”

Mid-market rent accounts for 10-15% of Hillcrest’s total programme, equivalent to 223 homes out of 319. Its development programme for 2014/15 to 2015/16 commits to funding up to 650 new homes across Tayside and Edinburgh.

"We need more genuinely affordable homes to rent."

These different grant regimes give landlords in Scotland and Wales an advantage in developing homes for social rent. In England, a mixed picture emerges of some housing associations that have made active decisions to build some social rent, and others that have had this forced on them by planning constraints.

Some councils are wedded to demanding social rent – as opposed to affordable rent, shared ownership or any other tenure – when they reach planning gain agreements. This, no doubt, is down to a variety of factors including the need for genuinely affordable homes, local politics and an ideological opposition to the alternatives.

Fortis Living is by proportion England’s largest developer of homes for social rent, with 227 of its 525 completions being for this tenure in 2016/17. Simon Vick, assistant director of growth and development at the 15,000-home association, is among those impelled to social rent by the planning system. He says: “We supply social rent as we have seen a surge in development across the main areas where we operate in Warwickshire and Worcestershire, with a lot of Section 106 deals by local authorities that prescribe social rent, so we are quite happy to do that in those.

“Our social rent all comes through Section 106, and we do affordable rent through other programmes for which we get grant funding.”

Mr Vick says Fortis Living is “quite strong financially so we can make it work and the difference between social rental and affordable rent is on average about £10 week, so it is not huge”.

Fortis has also been in the curious position of building some 100% affordable developments, where the local authority concerned has insisted on social rent for the Section 106 element, where Fortis must therefore meet the cost as it cannot get grant for that portion.

The propensity of Midlands councils to demand social rent in their planning gain agreements is also a factor for 39,000-home Orbit. Chris Jones, development director for the Midlands, says: “The vast majority of the homes we provide for social rent are located across the Midlands and delivered as a requirement of Section 106 agreements. If we are developing with grant contribution, then we are required to charge affordable rents, not social rents.

“Therefore our policy is to meet the requirements of either the Section 106 planning agreement or the Homes and Communities Agency (HCA) funding agreement and charge the appropriate rent.”

Such planning gain requirements have been more troublesome for 20,000-home Midlands-based Longhurst, says Nick Worboys, director of development and sales. A large part of its programme is Section 106.

“Local authorities in the Midlands especially seek social rent,” Ms Worboys says. “It’s not ideal, as we end up with mixtures of affordable rent, shared ownership, and social rent for the Section 106 element, so it isn’t great from the management perspective and you get neighbours paying different amounts for similar homes and it has never been our plan to do that.”

To meet its business plan’s rent targets more readily, Longhurst would prefer tenures that produce more rental income such as affordable rent or shared ownership, “but the local authorities seem deeply wedded to social rent”, Ms Worboys notes, adding that some councils “just will not accept rent to buy as an affordable tenure even though the HCA says it is. It is not very forward thinking”.

Ms Worboys adds that since Longhurst builds some 600 homes a year, it “can carry some social rent, but if it became a sizeable part of the programme we would have to think twice as it would hit the bottom line”.

The exceptions are some of the lower-value areas in which Longhurst operates, such as Grimsby, where social rents exceed the 80% of market rate affordable rent level.

Network’s 24% of completions for social rent is in line with its growth strategy for 2016/21, and its programme split for 2015/18 is roughly a third social or affordable rent, a third shared ownership and a third market rent and sale. Its social rent programme, though, arises neither from policy decisions nor planning gain agreements.

A spokesperson for the 20,000-home association, based in the South East, explains: “The main reason for the high proportion of social homes we build is our extensive successful regeneration work with our local authority partners. These rents are ‘promised’ to people returning to the new homes after temporarily moving out during the regeneration work.”

L&Q and Sanctuary both say they are involved in social rent as a matter of deliberate policy rather than a consequence of the planning system.

Peter Martin, group director of development at 85,000-home Sanctuary, says: “Sanctuary is a housing association first and foremost. We believe in providing social housing to those who need it most and take our charitable objectives very seriously.

“We have made a business decision to invest in social housing, even where it may not stack up financially, because we think it is the right thing to do. We have developed and continue to develop significant commercial revenue streams that allow us to achieve this sustainably.”

Sanctuary is able to reinvest commercial revenue generated across its businesses – such as Sanctuary Care and Sanctuary Students – into social rent.

Affordability pledge

It is a similar story of social rent being ‘the right thing to do’ at 90,000-home L&Q. A spokesperson says: “L&Q builds high-quality homes to meet a range of needs and incomes. As a charitable housing association, however, we are anchored by our founding social principles. We have made a commitment that at least 50% of housing completions should be genuinely affordable to people on average and below average incomes, and we aim to maximise our annual output of social rented homes.”

Melanie Rees, head of policy at the Chartered Institute of Housing, says councils’ local housing strategies must take account of the mix of homes needed in the area concerned and then use the planning system to deliver this. “In many areas, homes offered at social rents are the only truly affordable option for a significant number of people and it is crucial that we build this type of housing where there is evidence that it is needed,” she says.

“We desperately need more genuinely affordable homes to rent, but it should be part of a wider approach to meeting the housing needs of each community.”

In England, the absence of grant for social rent homes means they get built either because a landlord actively decides that their mission requires this, or because a local authority requires this provision.

Theoretically, associations willing to build for social rent could be matched with enthusiastic councils. In practice, social rent provision is likely to remain a combination of idealism and pragmatism.