You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Having a mayor

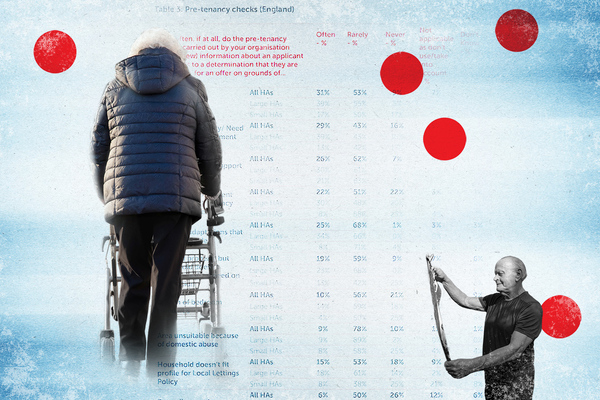

Recent devolution has seen a spate of metro mayors take office. Tom Wall finds out whether the new breed of municipal leader can change local housing policy. Illustration by Bill McConkey

Back in November 2014, the then Conservative chancellor George Osborne headed to Manchester’s gothic council chamber to sign an agreement he had been negotiating with 10 local authorities for months.

It created the first metro mayor outside of London and released devolutionary forces that could change the way housing is delivered in many of our biggest regions.

Mr Osborne called it a “massive moment” and invited “other cities keen to follow Greater Manchester’s lead” to get in touch.

They certainly did, with nearly 40 councils bidding for similar deals. In May, six regions elected metro mayors for the first time and others, such as Sheffield, are set to follow.

But what difference will these local figureheads be able to make to city regions desperate for affordable housing?

Simon Jeffery, researcher at thinktank Centre for Cities, which has been pushing for regional mayors for well over a decade, is largely optimistic about their prospects even though their powers are limited.

“I think they will be able to make a big impact. But there is a big caveat on that because anything that happens has to be agreed by the constituent local authorities,” he explains.

Collective consent

Their role is very different to that of London mayor Sadiq Khan, who can block large developments that do not provide enough affordable homes.

“Metro mayors cannot create plans that others must conform to. They have to be far more collegiate,” says Mr Jeffery.

But the mayors will be able to use the “bully pulpit” of their directly elected position to speak out on housing issues.

“There are local authorities in Manchester where already the turnout for the Greater Manchester mayor elections is higher than in local elections,” he says. “While the competencies for planning might lie at the local level, the mayors have the ability to shape public discussion.”

Two of the highest-profile metro mayors – Andy Street and Andy Burnham (see box: Meet the mayors) – have already used their status to go beyond their formal remit to highlight growing levels of urban homelessness.

Ex-John Lewis boss Mr Street, who edged a tight contest in the West Midlands for the Conservatives, has set up a regional task force to get people off the streets and Labour’s Mr Burnham, who won with a thumping 63% of the vote in Greater Manchester, has launched a foundation to end rough sleeping.

Some lesser known names are also interested in the issue. Cambridge and Peterborough’s metro mayor James Palmer wants to roll out a scheme that has all but eradicated rough sleeping in the East Cambridgeshire district council he used to head.

Moreover, the mayors, in their official roles as chairs of combined authorities, will be able to shape regional planning decisions and spatial frameworks, which set out the housing needs of entire regions.

“Once agreed, they have the powers to expedite these plans and get shovels in the ground sooner,” says Mr Jeffery.

On this too, the mayors have quickly made their presence felt. Mr Burnham has ordered the Manchester plan to be rewritten following protests against development on greenfield land, while Mr Palmer has signalled he is prepared to take on nimby residents to ensure “everybody has the house they can afford” in his spatial framework.

Some of the mayors will have a big say over existing pots of money for new housing. Greater Manchester’s mayor is in charge of loaning out £300m to developers building homes, mainly for private sale and rent.

Mr Burnham is campaigning to use the loan repayments to build affordable homes because critics have claimed that much of the fund has gone towards building upmarket city centre apartments.

“Metro mayors cannot create plans that others must conform to – they have to be far more collegiate.”

Mr Palmer has £100m to spend on housing development in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough. There is also an additional £70m fund earmarked for affordable housing in Labour-controlled Cambridge.

However, Paul Hunter, who authored a report on housing devolution for the Smith Institute, sounds a note of caution. He argues the mayors’ budgets do not even begin to match the scale of the housing crisis engulfing our biggest cities.

“They do not have enough power and resources to meet the scale of the demand for new housing, especially affordable housing,” he says. “They can do interesting stuff but the jury is out on whether it is enough to deliver on some of the promises that were made.”

According to his report, many of the regions do not have enough money to meet expected housing demand. Greater Manchester is short by £831m, the West Midlands by £945m, Liverpool City Region by £249m, and Cambridgeshire and Peterborough by £162m.

Limited borrowing

Mr Hunter also points out that the mayors’ borrowing powers are limited and using a community infrastructure levy on mainly brownfield developments is “unlikely to bring in much revenue”. Land remediation is so expensive, there is little profit left to tax.

He fears that difficulties in getting all councils to agree could “mean a watering down of spatial plans”, while hard-pressed public bodies will be reluctant to give away land for housing. “If you’re an NHS trust struggling for money, you are going to be looking for the highest return rather than acting strategically with a combined authority,” he says.

The mayors can set up mayoral development corporations. But these corporations only tend to work on vast regeneration projects. London, for instance, only has two mayoral corporations, which span the nation’s three biggest infrastructure schemes: HS2, Crossrail and the Olympic legacy. “They are likely to be used only sparingly,” notes Mr Hunter.

The Centre for Cities acknowledges these limitations but believes the mayors will eventually gain more powers from Whitehall. This has already happened in Greater Manchester, with Mr Burnham now in charge of police and fire services, and in London, where the mayor’s powers have grown steadily.

“I wouldn’t look at this picture as if it was going to be static. Manchester is already on its fourth deal since 2014,” says Mr Jeffery.

There are rebellious stirrings elsewhere, too. Tim Bowles, the West of England’s new metro mayor, had put Sajid Javid on notice that if he retained his job as communities secretary the mayors would come to him looking for more money and powers.

“Be warned, Sajid,” he says. “I’m going to be knocking on your door with the other guys, saying ‘we need a real commitment from you so we can start making a real difference’.”

Meet the mayors

West of England

Tim Bowles is not willing to get into the precise number of new homes the region requires but stresses that needs vary between inner city Bristol and rural villages in the Mendip Hills.

“In every area of the region there is a need for new housing,” he said on his second day in charge. “I also know from my months of being on the campaign trial we have got different challenges.”

Mr Bowles, a marketing manager and Conservative councillor, recoils at the suggestion that the housing market is broken. He prefers to say that it needs “a range of offerings”, including affordable homes.

He has already made contact with housing associations in the region and he cannot envisage any problems working with Labour-controlled Bristol, which wants to build homes at social rents. “We are motivated by trying to improve people’s lives. We have got the same objectives,” he says.

However, Mr Bowles has campaigned against a 3,000-home ‘garden village’ in Gloucestershire and is opposed to development on greenfield land.

“I entirely understand why people are concerned about where homes are being built,” he says.

Liverpool

Labour’s Steve Rotheram believes that housing is “one of the most urgent challenges” for the city region. He wants to build “truly affordable housing” including council homes. Mr Rotheram, who was Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn’s parliamentary private secretary, plans to set up a city-wide organisation to deliver new homes for sale and rent. He is also pushing for the Housing First approach to homelessness to be adopted, a key goal of Inside Housing’s Cathy at 50 campaign to end rough sleeping .

West Midlands

Andy Street, who left his chief executive job at John Lewis to run for mayor, wants to build 165,000 new homes by 2030 to keep up with population growth and ensure there are “enough affordable homes”. To protect the green belt, he plans to spend £200m on preparing and decontaminating brownfield sites. Mr Street has met with key housing associations in the region and wants to work with them.

Greater Manchester

Andy Burnham, a former Labour minister, railed against Manchester’s “dysfunctional housing market” during his campaign. He is trying to renegotiate the terms of existing funds so he can build affordable homes and he has set up a homelessness foundation to end rough sleeping.

Cambridgeshire and Peterborough

James Palmer, a straight-talking former dairy farmer and Conservative district council leader, is adamant that housing cannot be left to the market alone.

“I’m a free marketer. But we are in desperate need. There haven’t been enough houses built under successive governments in the UK,” he tells Inside Housing.

There are about 30,000 houses in the Local Plans but Mr Palmer says the region needs 70,000.

One of his pet projects is community land trusts, which allow groups of people to build and manage affordable homes on land gifted to them.

Mr Palmer has also been talking to housing associations about the role they can play in the county. “Housing associations are an important part. But I’ll be expecting more from them.”

Unlike the other mayors, he is upfront that green belt land might have to be used. “Nimbyism is a huge problem,” he says. “It is something I find very frustrating. I see it across the country. Everybody deserves an opportunity to live in a home of their own.”

Tees Valley

Ben Houchen was the surprise Conservative winner in Tees Valley. The 30-year-old corporate lawyer and sportswear brand chief executive has proved hard to track down since his victory, but in the run-up to the election he criticised “over development”. Instead, he wants to develop a new garden village in the region.

Related stories