The LPS files: hidden documents shed new light on the UK’s first building safety crisis

New documents from the National Archives and the personal collection of the late architect Sam Webb reveal the missteps that gave us a tower block disaster and a legacy of poorly built buildings – as well as lessons that reverberate today. Peter Apps and Hannah Brack report

On one side of the road are four-storey town houses – the classic architecture of north London. Built to house the growing ranks of middle-class Londoners in the 19th century, with space for a cook and a maid, these buildings are still here long after the society that created them has moved on.

Today they are split up into houses in multiple occupation – single-room housing for a melting pot of Londoners who can scrape together £1,000 or so a month for a bedsit.

On the other side of Crouch Hill, rising out of a raised grassy embankment, is a building that tells another history.

This is Ilex House, a dark grey concrete 17-storey block of council housing. It looks like an unremarkable, weather-worn relic of London’s ageing post-World War II council housing boom.

But look closely, and you will see something else. As you walk up the road towards it, you can make out big square slabs, six per storey, on either side of a middle crevice. It looks like it has been built with giant building blocks.

This is because, in a manner of speaking, it has. Ilex House is one of 740 high-rise buildings remaining around England (with a further 192 in Scotland) that were built during the boom of ‘large panel system’ (LPS) construction in the 1960s.

This building method, heavily backed by the governments of the day, involved pre-forming concrete slabs in a factory, driving them to site, and fitting them together with bolts and dry-packed mortar.

This fast method of construction appealed to ministers with housing targets to meet, but came with risk. With no supporting frame, every slab effectively becomes load-bearing, putting the building at risk of disproportionate collapse if just one joint fails to hold.

Sixty years on from their construction, these buildings pose a problem. Ilex House is one of an estimated 350 around England (and 59 in Scotland) that still have a mains gas supply.

This puts it in a higher risk category. It was a gas explosion that blew out a panel at the Ronan Point tower block in 1968, causing a collapse and five deaths, which brought the boom in this form of construction to a juddering halt.

It appears that life in Ilex House is none too comfortable. “It’s OK in summer, but in winter the water comes in through the walls,” one resident tells Inside Housing outside the building. We see video footage from a former resident of water leaking through the external walls.

“You can smell the cigarettes from the flat below,” adds another.

In the communal corridors on the 17th storey, the floors appear to bow towards the end of the corridor. If you place a coin on the floor, it rolls rapidly towards the wall.

The building is owned by Islington Council, who said structural surveys and risk assessments had confirmed the block to be “structurally sound and robust” (a full response is at the base of the article).

Ilex House and the other LPS blocks, especially those with gas, face an uncertain future. The Building Safety Regulator is reviewing their safety, and they face a reckoning: many may not match up to modern structural requirements and could end up needing either multimillion-pound refurbishments or demolition.

If so, this will be the end of a sorry story that began with decisions in the 1960s. Today, with help from the archive of the late architect Sam Webb, who supported the residents of Ronan Point and campaigned relentlessly throughout his life to make residents of these blocks safe, Inside Housing can shed new light on how this came to be.

This tower in Islington, and the hundreds of others around the country, are a result of these decisions. While those decisions were taken 60 years ago, they carry a strange echo of the problems we face today, and serve as a warning of mistakes we may be about to repeat.

Sir Keith Joseph’s political career was launched by his high-profile stint as housing minister in the Harold MacMillan government of the early 1960s, and this stint was defined – more than anything else – by a single policy: the heavy state backing he provided for industrialised building.

Sir Keith would go on to a long political career, serving in the cabinets of both Edward Heath and Margaret Thatcher, and being hailed as the Conservative Party’s “intellectual leader” as it devised a pathway towards a new Britain in opposition in the 1970s. But the buildings he had built in the 1960s cast a long shadow.

Before politics, Sir Keith had been to boarding school and then the University of Oxford, and served as a captain in World War II where he was wounded during the Italy campaign. After the war, he settled back into a civilian career and took up a directorship at Bovis, a company built by his father, Samuel Joseph.

Mr Joseph senior had acquired Bovis with a business partner and built it into one of the largest construction companies in the country. Sir Keith held on to his shares when he moved into politics and joined the government.

Appointed housing minister in 1962, Sir Keith had a big job. The country was still struggling to recover from the war. Inner-city areas remained bomb-damaged and ridden with Victorian slum housing. He had his eye on a very modern transformation. On 2 October 1962, he produced a document for the rest of the cabinet marked “secret”. It was obtained by the architect Mr Webb and shared with Inside Housing.

“We need a new impetus on housing,” the briefing said. “For various reasons, building in and for the great cities has not kept pace with the need. In spite of everything we have done, housing is still desperately short in many places.”

Young people could not get on the housing ladder. Homelessness, particularly in London, was surging. “Housing… is a source of bitter and constant criticism of the government, from all directions,” it said.

Sir Keith said that the construction of new housing – then around 300,000 homes a year and projected to rise to 325,000 – was too low to meet demand. “I want to aim at getting housing output up to 350,000 a year,” he wrote.

This was to be done by embracing the modern world of industry. Bricklayers, joiners and other traditional skills were for the past. The housing of the second half of the 21st century would be built in factories.

“We must make more use of industrial techniques,” he wrote. “Various methods are being developed here and in Europe which speed erection and reduce demands on building labour. These relate mainly to the building of high blocks… I shall foster these experiments and secure the large-scale adoption of the most successful systems.”

He said this would be tackled in the public sector first. Councils would be encouraged to place joint contracts that would give builders “an assurance of long forward programmes” with “a high degree of standardisation” – necessary to encourage private sector players to put up the large investments required to build factories.

A huge conference was held at Church House in Westminster, supported by Sir Keith. It was titled ‘Homes from the Factory’ and was sponsored by the Cement and Concrete Association.

The vision was taking shape. A document from the London County Council, produced in the same year, shows what this new technology would be. Titled Methods of Increasing Productivity in the Building Industry in Relation to Housing, the report also looked forward to a new world where traditional building was confined to the past.

“Whilst tremendous strides in productivity have been taking place in the manufacture of domestic appliances, motor-cars and other luxury commodities, the building industry, which is concerned with providing shelter for man’s essential needs, still continues to rely upon techniques related to handcrafts,” it said.

Instead, the document said, we should look to Europe – and the moves in France, Russia and Denmark to mechanise the housebuilding process. These countries were building pre-cast concrete slabs in factories, some weighing as much as seven tonnes each, and driving them to building sites on lorries, where they were moved into place with cranes.

In particular, the Larsen-Nielsen method – which was being developed in Denmark and exported around Europe – caught the eye of the report’s authors. This system, it said, “comes nearest to meeting our requirements”.

If this system was adopted, a factory could start production within a year at a rate of 600 to 1,000 dwellings in the first 12 months, it projected. Over time, this would be cheaper than traditional building – although not immediately, given the large upfront investment required to build the factory. The evidence from Denmark showed that with continuous production in the factory, “the cost per dwelling is very low indeed”.

But cost was a secondary consideration. The bigger advantage was speed. “What is important is to increase building production under the economic circumstances that exist at this time,” the report said.

The method would hugely increase productivity, it said. A team of five men, given one month’s training, would complete two flats in a day, it claimed.

There were concerns, though. The new trend towards maisonettes and “other types of more complex” housing may be difficult, given that “load-bearing wall construction is difficult to apply” using this method. The structural integrity was provided by the floor slabs, and the report said this had been demonstrated to be “satisfactory for blocks up to 11 storeys in height”. Above this height, the report said, “it is presumed the constructional by-laws would require greater rigidity to be provided”.

A further sentence added additional concern. In Denmark, where the system had caught on, its low costs made it possible for the builders to “win contracts for housing designed for other methods of construction”. “This is a remarkable achievement, but it is disturbing to find that Danish architects countenance misuse of the system in this way,” the report said.

But it is possible these concerns never made it to the eyes of policymakers. The document Inside Housing has seen was obtained from the National Archives. It is a draft. Editing notes are littered throughout – words added or taken away and additional clarifications noted in the margins in pencil by an editor. Both the two sentences above that raise concerns – one that implies a risk with using this system for the tallest buildings, and another that frets about its potential misuse for inappropriate building types – are crossed out.

Regardless of whether they made the final draft, such concerns were not enough to stop the momentum from a government that wanted to lift housebuilding at all costs. By 1963, Sir Keith had set a target of 400,000 homes a year, with the opposition Labour Party scrambling to beat him with its own target of 500,000. From now on, speed and volume at all costs were what the government wanted, and factories were the way to achieve it.

The system building revolution was underway. And for the companies placed to take advantage, it was an opportunity for huge profit.

With Sir Keith and his colleagues in central government driving for increased housing numbers, density restrictions were relaxed and the subsidy system for new council housing was tweaked to encourage councils to build high rises.

Huge tower blocks were built across the city using this method: at the new Broadwater Farm estate in Tottenham, and across Islington, Southwark and West Ham.

The new technology was subject to a ‘hard sell’ to local authorities from the manufacturers. Councillors were offered “various inducements, including lavish business entertainment and expenses-paid trips (sometimes overseas) to see the contractors’ systems in situ”, says the academic Peter Scott.

One of the major companies winning these contracts was Concrete Ltd, which had developed the ‘Bison’ system (similar to Larsen-Nielsen) and set up factories around the UK to produce the panels. In October 1963, the first 12-storey system-built block was opened by Sir Keith.

But Concrete Ltd was privately concerned about its investment. It had five factories and planned to build 3,000 homes in 1964. What if they turned out to have flaws or expensive maintenance costs? In November 1963, it appointed the Building Research Station (BRS) – the UK government’s building science laboratory, and a forerunner to today’s Building Research Establishment – to investigate a newly built block in Kidderminster. It sought feedback on liveability factors, including water penetration, sound insulation and the underfloor heating system.

“Had [this report] been acted upon in 1964 it would have required a drastic rethink of the principles of LPS”

The BRS initially said no. It wrote back to say that such a limited investigation would be “of very limited interest” and if they were to investigate, they would also want to study “structural design aspects” and “the methods of making the joints between units”. This “comprehensive appraisal” of the Kidderminster flats appears to have been what the BRS signed up to do – at a cost of £1,500 (£27,500 in today’s money).

The Kidderminster investigation was carried out and duly shared with the government. A copy of it is held at the National Archives.

But something appears to be missing. Because despite this agreement for a thorough investigation, including the structural elements, this is not what the report contains at all. In fact, it appears to be the “limited” review Concrete originally requested – giving a positive view on matters such as water ingress and sound insulation, without touching on the more difficult question of structural stability.

What did exist was a passing reference to a further report. The blocks at Kidderminster were finished by the time the BRS arrived, and so examining the joints would have been difficult. But the report does say that further investigations were carried out on a block under development in Rugby. This report, though, vanished. It was never submitted to government and never made public – even as the question of the structural stability of these new buildings was put under the microscope.

Inside Housing has found it. Contained in a separate file at the National Archives, it appeared entirely by accident while our researcher, Hannah Brack, was looking for a different document. On 28 February 1964, one of the BRS’s technicians attended a site in Rugby, where the firm was building tower blocks for the local authority. This short, two-page report should have set alarm bells ringing about the quality of the new construction being carried out all around the country.

“The relatively large number of defective panels in the structure is surprising,” the report said. “In one floor alone, there were four or five inadequate joints between panels as a result of misplaced steel loops or missing location bars.”

The reviewer also worried about the concrete used to fill the joints, and that the load on the slabs was actually passing through the bolts. This, they wrote, could cause “unsightly fractures and reduce the durability and even the stability of the structure”.

They were also unimpressed by the skill of the workers. “This is not the sort of job that can be done satisfactorily, safely and economically with what appeared to me to be an odd assortment of locally recruited, inadequately trained labourers,” they wrote. They felt that many of the defects were a result of “inadequate supervision of the works”.

Architect Mr Webb saw this report before his death, aged 85, in 2022. “Had [this report] been acted upon in 1964 it would have required a drastic rethink of the principles of LPS,” he wrote in an email. “[But] far too much money had been invested by the building industry into LPS, and too much political capital. I found every one [of the issues it describes] at Ronan Point.”

But the BRS would never issue such a warning. The eventual inquiry into the Ronan Point collapse would criticise its failure to do so. “We find it very surprising that the BRS appears to have taken no steps either to follow up the structural problems of system building, or to give warning of the danger of progressive collapse to the Ministry of Housing and Local Government,” the report said.

The new document shows that the BRS had taken steps to follow up on the structural problems. But when it found out about them, it had said nothing.

Meanwhile, the government’s enthusiasm for industrialised building continued apace. In 1964, Harold Wilson’s Labour Party had defeated the Conservatives, and Richard Crossman replaced Sir Keith as housing minister. Mr Crossman continued his predecessor’s enthusiasm for industrialised building.

In December 1965, Mr Crossman announced plans to increase the output of pre-cast concrete homes and flats to 100,000 a year, accounting for 40% of all new council homes. Councils were encouraged to sign up to contracts of at least two or three years, to give the builders the continuity of income they craved to invest money in factories.

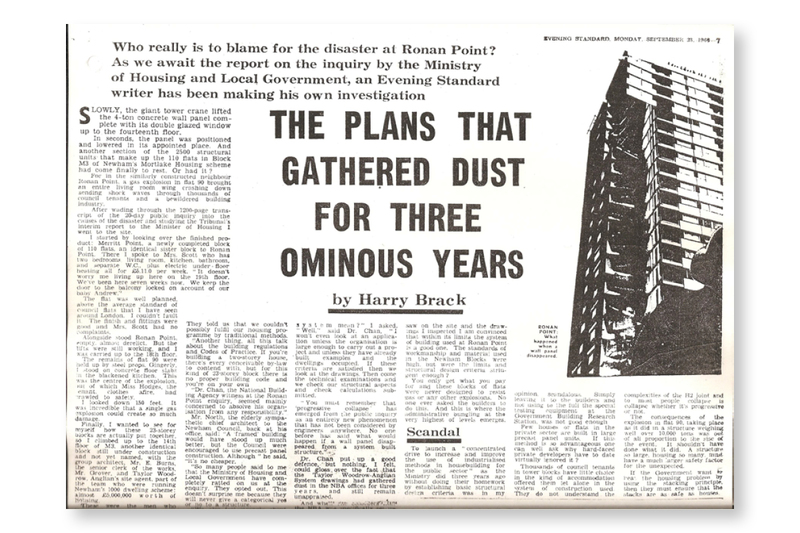

“As near as damn it we were forced into using this form of construction,” one clerk of works for a local authority told the Evening Standard in 1968. “In fact, if we didn’t use an industrialised system, [the Ministry of Housing] by implication threatened to stop the project. They told us that we couldn’t possibly fulfil our housing programme by traditional methods.”

While these blocks could be built quickly in factories, assembling them on site was much harder. This was before modern workplace safety standards, and labourers were hundreds of feet in the air with no scaffolding. They worked as quickly as they could, in order to get back down to safety, and there was no possibility of oversight. Their pay was also linked to how quickly they could complete the work – a process that incentivised corner-cutting.

And this corner-cutting was leading to serious dangers.

Taylor Woodrow was a private company that had been grown from the ground up by 16-year-old Frank Taylor and his uncle, Jack Woodrow. Its first development was a home for Mr Taylor’s family in Blackpool in 1916.

By the 1930s, it was building more than 1,000 homes a year and it floated on the London Stock Exchange in 1935. During World War II, it built military camps, airfields and munitions factories. After the war, it looked overseas, expanding into Africa, Canada, Australia and the Middle East.

But it also remained a major force in the domestic market and was a major donor to the Conservative Party. It formed Taylor Woodrow Anglian in 1962 along with Anglian Building Products, a firm that could produce 100,000 tonnes of precast concrete a year from its plant in Norwich, and won a license from the Danish company Larsen and Nielsen to use its system in the UK. Shortly afterwards, it won a contract with the London County Council to build public housing in London.

Thomas North, the borough architect in what was at the time called the County Borough of West Ham, in east London, had been taken on trips by contractors to view LPS building projects. He had been convinced that it provided the answer he needed to the borough’s acute housing pressures.

As the borough was an industrial dockland area, over a quarter of its homes had been flattened by the Luftwaffe and many of the remainder were in a parlous state. Despite building more homes than any other borough, it had a housing waiting list of more than 8,000, and 9,000 homes designated as slums.

Mr North selected Taylor Woodrow and Larsen and Nielsen to build a series of new tower blocks in the south of the borough, to be known as the Freemasons Estate.

He was given no reason to question this decision by the National Building Agency (NBA), which the government set up to advise on this form of construction.

The NBA had been sent the design drawings for the Larsen-Nielsen system in 1964. But the agency never considered the issue of progressive collapse in any of the certificates it had issued, with its thinking “limited by the horizons” of existing codes of practice.

“No one in the agency appears to have even thought to the many structural questions that have arisen in this inquiry,” the final inquiry report into the Ronan Point collapse would say. “We are bound to say that this exhibits a serious weakness in [its] thinking.”

Run by the same ministry that was pushing industrialised building as the solution to the housing crisis, there are some who believe the NBA understood that it was not supposed to deliver bad news.

“After pushing industrialised building as hard as they could, [the government] let the building regulations moulder and failed to back it with a proper programme of research and tests,” a senior industry figure told the Evening Standard for the same article mentioned above.

The journalist who wrote it – Harry Brack, the father of Hannah Brack, who uncovered the documents relied on in this piece – did not mince his words. He described the situation as “scandalous”, noting that the building technique was reserved to the public sector and therefore only the poor and working class.

“If this method is so advantageous one can well ask why hard-faced private developers have virtually ignored it,” he wrote. “Thousands of council tenants have little choice in the kind of accommodation offered them, let alone in the system of construction used.”

But with no warning from the NBA, the borough of West Ham was reliant on the structural engineers it appointed to oversee Taylor Woodrow Anglian’s work to ensure it was safe. But this engineering firm was Phillips Consultants, a wholly owned subsidiary of Taylor Woodrow. The contractor had demanded that its own firm be appointed.

Four years later, in early March 1968, hundreds of residents began to move into the nine blocks the contract had delivered. The flats were well proportioned, and offered a huge improvement on the single rooms many families had previously shared. Running water. Indoor toilets. Gas cookers. Not to mention the incredible vista of the Thames snaking through London and out into Essex. They reached 22 storeys into the London skyline.

What the residents didn’t know – and couldn’t know – as they unpacked their possessions and examined their new homes was a particular danger in the corner of each flat. The structure of these towers relied on a so-called ‘H2’ joint, which held the structure together where the floor slabs met the external wall.

These should have been packed with dry mortar for support, but this mostly hadn’t happened. Instead, the whole pressure of the tower block rested on the bolts that held the heavy concrete slabs together – just as the BRS report into the Kidderminster blocks had warned of three years previously.

Later investigations would reveal that instead of mortar, the joints had been stuffed with newspaper, tin cans and other rubbish from the building site, as the gangs of labourers motored to finish the job as quickly as possible. Should one bolt fail, a huge concrete slab would come crashing down into the slab below, causing the entire building to fail. It would not take long for this risk to be realised.

What happened at Ronan Point?

At 5.45am on 16 May 1968, a resident named Ivy Hodge on the 18th floor woke early and went to the kitchen to make a cup of tea. In the years that have followed, it has always been reported that she lit a match to light the stove for her kettle, and unwittingly ignited a gas cloud that had leaked out from her oven during the night. This was the conclusion of the later inquiry into the blast.

But the documents seen by Inside Housing suggest a different possibility. Ms Hodge always said she had no memory of lighting a match. One moment, she was filling the kettle at the sink, the next she was lying on her back covered in water. The inquiry concluded that she had lost her memory after being knocked unconscious by the blast.

However, the writings of Mr Webb and supporting historical documents, seen by Inside Housing, cast doubt on this conclusion. They suggest instead that an electrical fault may have caused a small explosion, which then caused a gas leak and a further, second explosion which triggered the collapse.

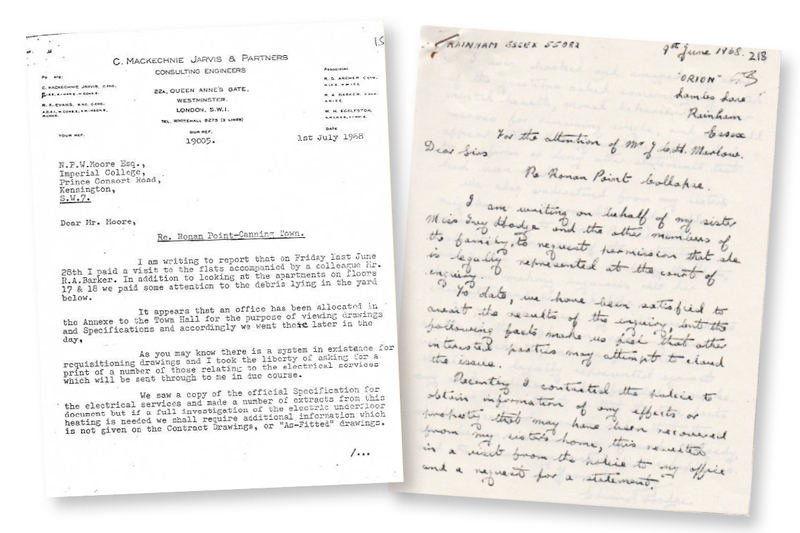

A report from consulting engineers C Mackechnie Jarvis and Partners, for example, found odd electricity readings in her flat “amounting to thousands of units against hundreds elsewhere”. The engineer said he would like to make further inquiries about this with the London Electricity Board, but left it in the hands of the inquiry. These investigations were never carried out.

Further evidence pointed to a malfunction in the underfloor heating in the surviving four flats on Ms Hodge’s floor. One of her neighbours reported very high temperatures in her living room before the blast.

Emails from Mr Webb show that he believes there was a first electrical explosion, and then a second one from gas. Indeed, 18 separate residents later reported hearing two explosions before the collapse, but this evidence was dismissed by the Ministry of Defence in a classified briefing to officials, seen by Inside Housing, because “most witnesses are not experienced observers of explosions”.

Nonetheless, what matters more than the explosion is what followed it. The blast was enough to merely blow Ms Hodge backwards and leave her with minor burns on her hands. But for this fragile, badly constructed building, it was too much to sustain. The bolts on the H2 joints in Ms Hodge’s kitchen failed. The huge floor slab fell, crashing onto the slab below in an enormous cloud of debris, furniture and dust. Bang, bang, bang – the slabs went on down the tower, gathering momentum and weight in an enormous rush of falling masonry that ripped through the corner of the building in seconds.

It was early. Most residents were in bed. The tower was not yet fully occupied. This is all that prevented an enormous loss of life. As it was, four residents (Pauline and Thomas Murrell, Thomas McCluskey and Edith Bridgstock) died in the collapse – crushed instantly under the falling concrete. A fifth, Ann Carter, died in hospital later, and 17 others were injured.

Londoners would see the first images of the wrecked corner of Ronan Point later, as they looked at the front page of that day’s Evening Standard, which carried an aerial shot of the wrecked corner of the block. “Why? Why? Why?” read the headline.

There were those in Whitehall who knew the answer: a hubristic, headlong lunge into a new method of building that had not stopped to consider the safety of the working-class people who would live in the impressive new structures. But this was not the answer that would be immediately offered.

At first, the industry rejected the claim that the building was unsafe, insisting instead that it was the explosion that had caused the collapse. A local media report quoted Mr North, standing outside the wrecked building, and insisting it would be safe for residents to return – if they could only be persuaded that it was safe to do so.

As the historian Holly Smith wrote, he would later tell the inquiry into the collapse that the block “stood up to [the explosion] surprisingly well – there is no sign of any structural weakness whatsoever”, while the managing director of Taylor Woodrow Anglian insisted that “there is not the slightest indication that there is any structural failure”.

Another official insisted that the block’s design had helped it withstand the explosion. “If the block had been built by ordinary methods I shudder to think what might have happened,” he said.

The contractor claimed that the explosion had been enormous, with a force of 600 pounds per square inch.

As a result, scrutiny fell on the innocent Ms Hodge and her oven. “Pictured by one newspaper heavily bandaged and flanked by a nurse, Hodge was questioned about her decision to ask a neighbour to install her [gas] cooker rather than a qualified [engineer],” wrote the historian Shane Ewen.

Of course, if Mr Webb’s theory is correct, it was the professional who installed her underfloor heating who triggered the explosion, not Ms Hodge’s neighbour (a Mr Pike, who was also questioned at the inquiry).

Such was the scrutiny falling on Ms Hodge that her brother wrote a letter to the inquiry asking that she be provided with legal counsel. He said he had been “shocked and amazed” that investigators had questioned her “mental health, moral behaviour and reasons for remaining single”.

“We also understand from my sister’s neighbours in Thorne Close [her address before moving to Ronan Point] that a solicitor from one of the contracting companies instructed in building the flats has been making inquiries into her character and personal life,” he wrote.

Inside central government, though, there was fear about the revelation of “embarrassing issues” relating to this use of construction style, which successive governments had so noisily backed. But not enough to stop the train of systemised building.

In fact, a further memo, this one unearthed by the historian Ms Smith, shows the Ministry for Housing directing officials to continue approving systemised building schemes, even after the collapse to prevent “unnecessary alarm among people occupying flats built in this way”. The memo notes that doing so would “incur the risk of another accident”.

Eventually though, the focus on Ms Hodge and her oven would clear. Engineers determined that the explosion had a force of just three pounds per square inch. Instead, the focus fell on the H2 joints and the dangerous form of construction that turned this relatively minor gas explosion into a building-wide disaster.

The blast in the kitchen was a minor event, the inquiry concluded, and the collapse had been a result of flaws “inherent in the design of the building”. But it stopped short of attributing blame to either the designers or builders of the block, or even the government. The collapse was almost presented as a simple, tragic accident – the kind of thing that happens from time to time in a complicated society. It said LPS building should continue, providing it was done with greater effort to avoid collapse.

Nonetheless, the inquiry did determine that further work needed to be done to make other blocks safe. Its recommendation was that blocks around the country should be appraised, have their gas removed if they were at risk and be strengthened where necessary.

“With taller system-built blocks – and in this country there are already some 30,000 flats in such blocks – the risk enters new dimensions. All these buildings should therefore be examined as quickly as possible,” it said.

The government sent out circulars to local authorities to tell them to strengthen the buildings to survive certain levels of pressure per square inch.

In a bad-tempered meeting between local authorities and government ministers in 1969, councils insisted that the government should pay for repairs, saying they had been pressured into using the technology. But ministers refused to put up funds for more than 50% of the costs – with the rest coming from local authority budgets. Ironically, the original contractors were often appointed to carry out the strengthening works.

“With taller system-built blocks – and in this country there are already some 30,000 flats in such blocks – the risk enters new dimensions. All these buildings should therefore be examined as quickly as possible”

As the 1970s progressed, and with cash short and a distracted central government failing to provide oversight, many simply did nothing. The blocks, and the risks they carried, were forgotten over time.

As for the builders who had piled into system building, they continued to lobby government for continued support for their method of construction. In December 1969, just 18 months after the deaths at Ronan Point, a representative group of system builders met with the housing minister to argue that the “falling demand for industrialised building” was damaging their industry.

Just 33,000 such homes would be delivered next year, despite capacity to build 82,000. The group of builders warned that as well as economic strife caused by inflation, rising interest rates and public sector austerity, Ronan Point had “created doubts about the reliability” of their building method, and bemoaned the fact that the post-inquiry requirements for strengthening work “discriminated against” them, and were being applied too judiciously by London boroughs.

They called for changes to the building regulations to loosen the restrictions on their product, and for higher rents to be billed to council tenants to pay for their rising costs, as well as guidance to be given to local authorities to dissuade them from “insisting on stiffer guarantees for system building”.

They did not get everything they wanted – although the minister did commit to looking into the increased use of industrialised building in the new towns being built outside major cities.

System building dropped out of favour, as large, reinforced steel construction became preferred as a way to meet requirements for structural safety and councils moved away from high rises. System building dropped from 42% of local authority housebuilding in 1969 to 5% by 1977.

The lucrative package deals with local authorities were at an end. A series of corruption trials in the 1970s would shed light on a shady world of bribes and inducements, often involving PR companies working for contractors, who would hire councillors to secure contracts for them. This would ultimately culminate in the high-profile John Poulson corruption scandal.

As states moved away from direct commissioning of housing and cut back public spending in the 1980s, the steady high production volumes needed to make the system building model viable died away. Larsen and Nielsen went bust in 1997.

But the mistakes of this period would not simply disappear as the world moved on. And neither would the buildings the era had given us.

As the 1990s began, a new technological idea emerged. Old high-rise buildings could be improved with over-cladding of insulation. Again, reports about the dangers were buried, licenses were offered without proper consideration and contractors piled into a new, lucrative way of taking money from local authority contracts. And 49 years after Ronan Point, Grenfell Tower would suffer an avoidable disaster delivered through the failure of government and industry.

As for the LPS buildings, there has not been another fatal collapse since Ronan Point came down in 1968, but their life since has not been happy. Over time, the gaps in their concrete walls have started to let in rain water, and the buildings have earned a reputation for being cold and damp.

After the Grenfell Tower fire in particular, new surveys resulted in many blocks being demolished, including those in Rugby, where the hidden BRS report had warned of their poor structure in 1965. This number will increase in the coming years.

And who knows how long we will go without a repeat disaster? Increasingly extreme weather will be wearing on the ties between the slabs in these buildings. Across England and Scotland, more than 400 towers still have gas. It would only take one accident to bring down a tower, and we continue to gamble with this risk.

In 2022, a civil servant who had been trying fruitlessly to get the government to act with more urgency on these blocks resigned, warning that the country was risking another “Grenfell-style disaster”.

And what about the buildings we are developing today? We have once more reached a position where the government is competing to increase the rate of housebuilding rapidly, and facing pressure from the private sector to release it from regulatory burdens to meet the targets.

One can only hope that this time, ministers remember the lesson: unsafe buildings will still be here long after the political climate has moved on.

Update: at 4.00pm, 02.09.2025

Inside Housing contacted Islington Council ahead of publication regarding the issues at Ilex House in Crouch Hill. The council responded post-publication with the following statement:

John Woolf, executive member for homes and neighbourhoods at Islington Council, said: “We are committed to maintaining the highest safety standards across our housing stock, ensuring that all residents live in secure, well-maintained homes.

“Ilex House is currently undergoing assessment by the Building Safety Regulator for certification. We have submitted all required documentation, and the timeline for this process is determined by the regulator.

“As part of our own due diligence and to support this process, we have completed detailed structural surveys and type 4 fire risk assessments. These confirm that the building is structurally sound and robust. While some remedial actions have been identified, none are urgent or require interim safety measures. These will be addressed through a planned programme of works.”

Recent building safety articles by Peter Apps

Building Safety Regulator rejects nearly 75% of cases in early figures

Almost 75% of existing buildings so far assessed by the Building Safety Regulator (BSR) have failed to meet the standards required, figures shared with Inside Housing reveal

What is going on with Building Assessment Certificates?

The Building Safety Regulator is currently considering safety cases for 1,454 tall buildings. Its decisions could mean a major new era of the building safety crisis is about to begin. Peter Apps reports

A final reckoning: the future of LPS buildings under the Building Safety Act

Structural and fire safety issues in high rises built using the large panel system method of construction means housing associations face an expensive choice between remediation and demolition. Peter Apps investigates

BSR is ‘preventing unsafe homes from being built’, deputy director says

The Building Safety Regulator’s (BSR) processes are preventing unsafe homes from being built, with applications rejected for “fundamental” failures to show compliance, its deputy director has said

‘Assure yourself, and you will have a much easier time assuring us’ – in conversation with the Building Safety Regulator

Inside Housing’s contributing editor Peter Apps meets Tim Galloway, deputy director of the Building Safety Regulator, to talk about delays, rejections and how the sector could navigate the new system more smoothly

Sign up to our building and fire safety newsletter

Sign up to our new revamped building and fire safety newsletter, now including a monthly update on building safety from Inside Housing contributing editor Peter Apps.

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters.

Related stories