You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

New Shelter chief executive: ‘Our role might need to evolve’

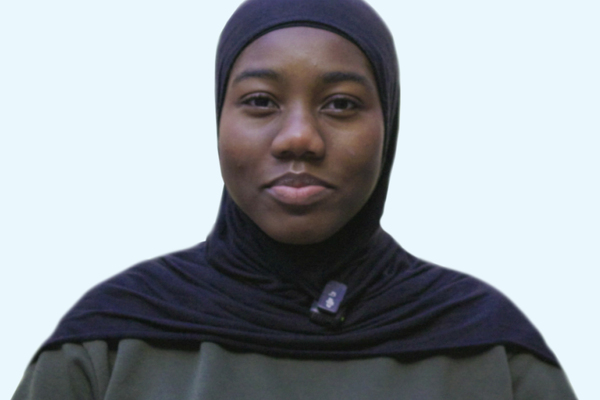

Sarah Elliott stepped into the role of chief executive of Shelter in September, just before the Renters’ Rights Act was written into the statute books. In her first in-depth interview, she talks to Ella Jessel about piñata parties, staff strikes and leading from the front. Photography by Belinda Lawley

Just a few weeks before Christmas, homelessness charity Shelter threw a party at its east London HQ to celebrate the passing of the Renters’ Rights Act. There was even a piñata emblazoned with ‘Section 21’.

One of those to take a turn with the stick was Shelter’s new chief executive, Sarah Elliott. She took over the top job in September, following the resignation of Baroness Neate earlier in the year. “It was full of sweets, and everyone had a chance to smash it,” she says with a laugh.

Ms Elliot came to Shelter from the National Council for Voluntary Organisations (NCVO), an umbrella group she led for more than five years. She arrived in the top job at the homelessness charity as it was riding high.

In the housing world, where victories can feel few and far between, 2025 bucked that trend. The Renters’ Rights Act was preceded by the announcement of £39bn in funding for affordable housing, while the long-awaited homelessness strategy arrived just before Christmas.

Taking a breath to celebrate Shelter’s role in such “once-in-a-career” wins was important, Ms Elliott says, but she points to the deepening homelessness crisis as a clear caveat.

“We’ve won a lot of the arguments, but all the numbers are still going in the wrong direction. None of us can sit here and say we’re so pleased with ourselves, because there’s 172,000 children in temporary accommodation.”

With the charity at a crossroads, Inside Housing visited Ms Elliott at Shelter’s HQ to find out more about the charity’s new head, and how she plans to turn campaign success into lasting change.

From charity shops to chief executive

Shelter’s London office is located slap bang on Old Street, inside a red-brick building with ‘FIGHT FOR HOME’ painted across its ground-floor windows. Inside, the open-plan space feels more like a campaign headquarters than an office, full of staff chatting and walls covered in posters.

We’re taken to a quieter upstairs meeting room with views over the City fringes to wait for Ms Elliott. As the photographer clicks away, Ms Elliott takes her seat, rueing that her yellow top is not in keeping with the charity’s trademark red logo painted on the wall behind her.

A “proud Northerner” who grew up in the seaside town of Scarborough, Ms Elliott speaks with a slight Yorkshire accent. Her dad was a youth worker while her mum ran a charity shop. “It has been fascinating – now I’m overseeing a chain of charity shops,” she says.

“My brother was also disabled, in the ’80s, when disability rights weren’t what they are now. So all I ever really wanted to do was go and work in charities and change things and tackle social injustice. In that respect, Shelter is very much a dream job.”

Ms Elliott has spent most of her career leading charities, including the Epilepsy Society and the Neurological Alliance. She also had a brief spell in local government in the mid-2000s, working under Ken Livingstone at the Greater London Authority. That was her first brush with housing, working with planners on the early stages of Crossrail to look at how transport can encourage housebuilding.

So why homelessness? “It’s our strapline, but home really is everything. It sounds like I’m quoting a corporate slogan, but I really believe it.”

As a newcomer to the sector, she has been surprised at just how “broken” the system is, and points at the asylum system and UK prisons as particular drivers towards homelessness.

One of the first things she achieved, before even officially joining, was running a half-marathon for Shelter. “I’d pretty much signed the Shelter contract, and then got an email saying, ‘Oh, we’d also like you to do a half-marathon’. I can’t say I enjoyed it. But it was leading from the front, I think they call it.”

I don’t entirely believe her. Dhivya O’Connor, former chief executive of the Cherie Blair Foundation for Women and creator of The Charity CEO Podcast, describes Ms Elliott as a “serious athlete” who once cycled 100km – further than London to Brighton – “just for fun”.

Outside work, Ms Elliott’s two boys – aged eight and 10 – keep her “very busy”, she says, and the family is active, with hobbies including skating, running and sea swimming, though there is less opportunity to do that now she lives in “landlocked Buckinghamshire”.

She bonded with Ms O’Connor when they were both newly appointed interim CEOs – Ms Elliott at NCVO and Ms O’Connor at the Chartered Institute of Fundraising – with young children. And aside from her sporting prowess, Ms O’Connor says Ms Elliott is “hugely experienced in convening and leading change” at both a grassroots and a national level and will bring this sense of “purpose with action” to Shelter.

Era of execution

The Renters’ Rights Act comes into force in May and has been a major campaigning area for Shelter over the past six years. The charity has also long been banging the drum for more social housing to be built around the UK.

The £39bn Social and Affordable Homes Programme (SAHP), unveiled last spring, was described by the charity as a “watershed moment” and an opportunity to start a bold new chapter for housing.

But there are plenty of details to shake out, and of course, the funding won’t come close to delivering the annual 90,000 social homes a year Shelter is calling for. The SAHP has instead set a target of 180,000 social homes spread across a decade-long programme.

“I think we’re very pragmatic, and I think our role will need to evolve”

Ms Elliott sees her role as making sure that changes to renters’ rights and social housing commitments actually happen. “I’ve come in at a really exciting time, with these big wins in the sector. So I feel the real responsibility now is how we bank those and build on them,” she says.

“We need to work with councils, with housing associations, work with developers to make sure that the social homes actually do get built and get spades in the ground, which is a slightly different role.

“Similarly, with renters’ rights, how do we enforce rights in a context where local authorities are really, really short of resources? How do we work as a partner in that system to make these things a reality?”

Ms Elliott thinks there might be a need for Shelter to adopt new tactics. She describes her plans for the charity to take a “convening” role to get different parts of the industry around the table. “I think we’re very pragmatic, and I think our role will need to evolve.”

Ms Elliott has, for example, already had a “constructive meeting” with the chief executive of an association representing private landlords, where they discussed the impact of the upcoming changes to Section 21 notices.

Does this signal a less combative approach than her predecessor Baroness Neate, who became something of a thorn in the side of the private rented sector? During her tenure, Baroness Neate was outspoken in her criticism of private landlords, accusing them of getting away with “cutting corners” on housing conditions and, amid fears the Renters’ Rights Act would be watered down in 2024, accused the government of being “too cowardly to stand up to a small minority of landlord MPs”.

“Where there are rogue landlords who are not doing the right thing, we clearly will not be on their side,” she replies. “But I do think we’re going to have to work as a [collective] if we’re going to improve the system and end homelessness.”

Working collaboratively has brought her success in the past. Her work in Westminster while head of NCVO resulted in the Civil Society Covenant – a set of principles designed to help build effective partnerships across civil society and government.

Ms Elliott argues that to “shift the dial on something as systemically unjust as the housing system”, it will take a variety of approaches, from what she calls her “geeky policy work”, to bringing diverse sector groups around the table, and exploring how to empower people locally.

But all this won’t stop Shelter being an “uncompromising campaigner”, Ms Elliott insists.

“It’s in our DNA – and it’s a really important role to play. We’ve seen that you can win policy campaigns only for the political will to change. So again, we cannot be complacent.”

Homelessness strategy

Before Christmas, the government announced its National Plan to End Homelessness. It is the first blueprint to address all types of homelessness and comes as record numbers of households are living in temporary accommodation in England.

A total of 132,410 households were living in temporary accommodation as of June 2025, with the total number of children now reaching 172,420. Yet the sector was lukewarm on the cross-government strategy designed to tackle the crisis.

Can Ms Elliott sum up the strategy in one sentence? “Positive that it’s focusing on prevention, but doesn’t address the underlying causes of homelessness,” she says.

One of its key omissions, Ms Elliott says, was its failure to unfreeze Local Housing Allowance rates, which had been a key ask from the sector. If the government had committed to this, would that have changed Shelter’s view?

“We’ve got to look at how we kind of strip discrimination out of not just a broken housing system, but a biased housing system”

“I think we’d have had a more positive take on it, but I think we would also then have said the only way to end homelessness for good is to build 90,000 social homes. We were very careful to say at the time that the focus on homelessness and the money committed is really positive.”

I’m keen to get a sense of what Ms Elliott thinks about the strategy’s vision, and if she thinks its headline target to halve long-term rough sleeping was ambitious enough.

She defers back to Shelter’s official position: “Our response was really clear – nobody should spend the night in the streets. If you’re at risk of spending that in the streets, you should have access to support and emergency accommodation.”

Union deals

In recent years, Shelter has come under scrutiny for its own staff’s pay and working conditions. Just before Christmas, around 500 members of the union Unite were balloted for strike action. It followed “unprecedented” walkouts at the charity over pay and conditions back in 2022.

The recent strikes were called off when the charity and the union reached a deal involving reducing the working week from 37 to 35 hours, which equates to more than a 5% pay rise, as well as two extra days of annual leave.

Ms Elliott says she is “really pleased” to have reached an agreement with the trade union, adding: “It means we can be laser-focused on the fight for home and the right to a safe home… which is what I’m here to talk to you about today.”

What is on her priority list at Shelter in the coming months? While ramping up to 90,000 social homes a year is the “ultimate prize”, she says, in the short term the aim is supporting those who are homeless today.

Discrimination is also high on her agenda: “We’ve got to look at how we kind of strip discrimination out of not just a broken housing system, but a biased housing system.”

Here, she is wasting no time. As we part, she heads off to meet race equality thinktank The Runnymede Trust, Shelter badge firmly attached to her lapel.

Sign up to Inside Housing’s Homelessness newsletter

Sign up to Inside Housing’s Homelessness newsletter, a fortnightly round-up of the key news and insight for stories on homelessness and rough sleeping.

Click here to register and receive the Homelessness newsletter straight to your inbox.

And subscribe to Inside Housing by clicking here.

Already have an account? Click here to manage your newsletters.

Related stories